There is nothing better than witnessing the perfect touch, a ball plucked out from the sky and stopped dead in it’s tracks. You hear the crowd in awe, that’s what we pay our money to see. For the special players, it’s a regular theme; Marcelo trapping a ball that’s flown from 50 feet in the air with the sole of his foot, Neymar with his trademark behind the leg touch, Mahrez receiving a wing to wing switch.

This is what we’ve come to know as ‘technique’, the aesthetics of individual play and we’re in love with it. And what better way to improve this individual aesthetic style than to drill it into our players. Repetition after repetition. So, why then when it’s drilled so much, is it still so rare to see?

Young players around the country pay hundreds, if not thousands of pounds per year to improve their so called ‘technical ability’. The internet is riddled with 1v0 practice, high speed touches around mannequins and cones and shooting into an empty net. This all seems fine on the surface and surely the more our players repeat the drill, the better they’ll be. But does this actually make our players better at football?

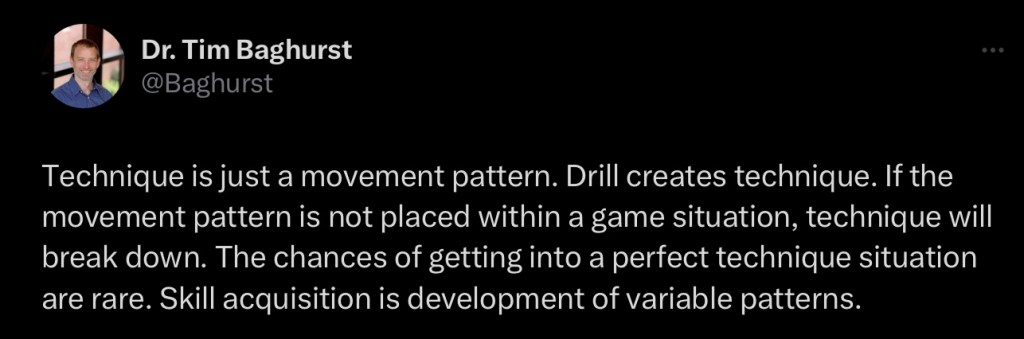

The view of ‘the more you practice and the more experience you have in something, the better you’ll be’, seems a logical one. However, what if we are forcing our players to repeat something so far removed from the actual game, that it actually doesn’t help, it hinders?

What if our misunderstanding of what technique actually is, underpins the work we do with our players? What if the technical training that has become a main pillar in the way we develop our young footballers, only really acts as a placebo for learning and improvement. What if consistently drilling players in movement patterns builds co-ordination and confidence, but not a lot else?

We’re going to break down what technique is and how we should go about developing it.

Patterns

Often when we talk about ‘technique’ we are actually talking about movement patterns or action capacity. Movement patterns are those prescribed movements which we impose on the players in an isolated environment and then expect them to notice the opportunity to use them in a contextual environment later on. Patterns such as; receiving side on, passing patterns, 1v0 ball manipulation, turns and beat the man moves. Learn the pattern, input the pattern. The problem is, we forget about the where and the why.

I’ve seen so many young players drilled in receiving back foot, side on and then on game day, not look around them and lose the ball. They’re then greeted with shouts from the sideline of ‘scan!’ It’s time we took more responsibility with what we do in the practice environment and how this affects what the players do on game day. If you don’t practice receiving vs opposition in training, how will the player ever be able to cope with this in the performance environment?

Action capacity is the range of which a player can perform an action, for example, when talking about ball striking, we are not talking about how a player can strike a ball in a variety of ways, we are often talking about how a player can play a 50 yard pass or shoot from range. The capacity of this player’s action underpins what he\she can do when it comes to opportunities to act in the performance environment. If you can play a 50 yard pass, and your teammates can not, new affordances (opportunities to act) are available to you.

So aren’t developing these prescribed patterns and action capacities important? Yes and no. Having the ability to rake a ball from one side of the pitch to the other is a good asset to have, however not necessary to be a good player. A good player will find ways to open opposition defences regardless of their action capacities and individual constraints. And the same goes for prescribed turns and passing patterns, they are not essential for developing a top level football player. What is important is that players notice opportunities to be functional.

These movement patterns and action capacities are usually trained unopposed, out of context. They act as a placebo for the player. Maybe because the reps can be counted. ‘I’m 100 touches better than I was yesterday.’ However, the quality of the information in these practices is not representative of game day information. We are not preparing our players for their performance on the weekend.

So how do we expose a player to opportunities to develop an action capacity? Fortunately, it’s not very hard to do this in a contextual environment.

For example, if you want to improve the action capacity of an individual’s passing, just make the pitch longer or wider – depending on what you’re other aims are. Make the distances bigger, then the players should self organise to complete the task set. If they aren’t looking for these opportunities, you can highlight that there is space to play further on, and challenge them to take the next few opportunities to play into those spaces.

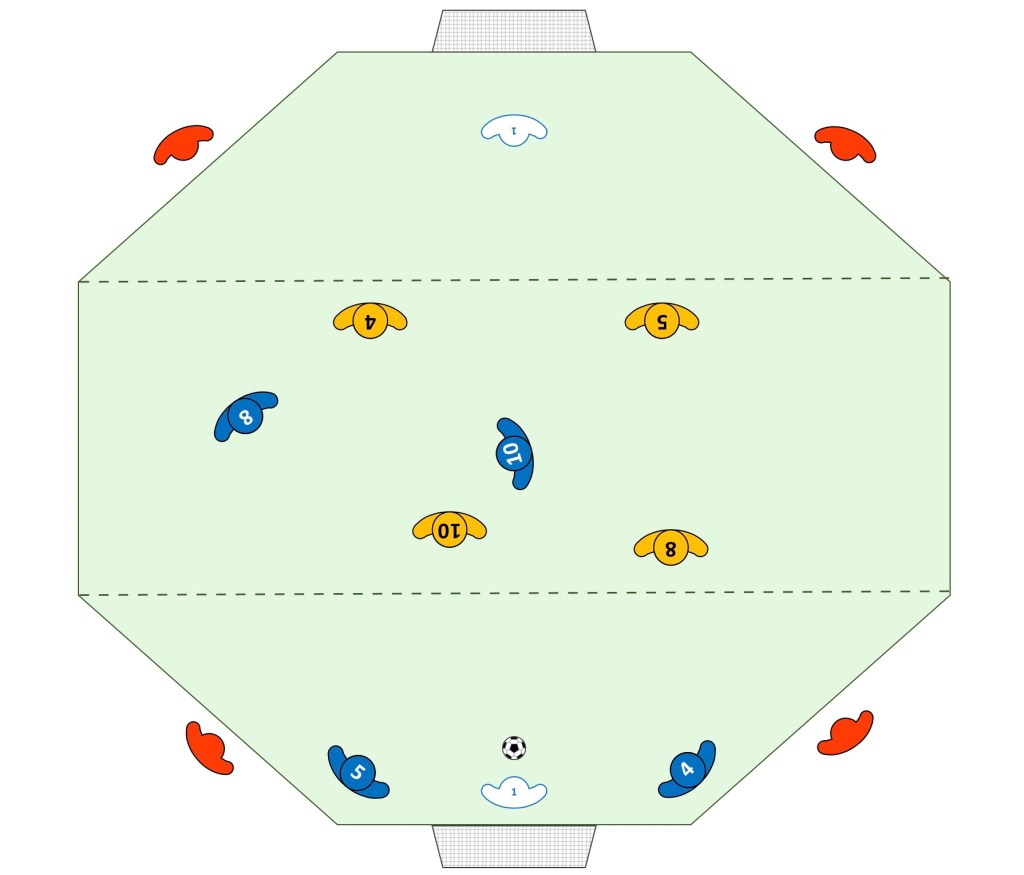

In the above practice, 4v4+4(+2GK), players are asked to score in anyway they deem necessary. They can play around, through or over. The offside lines for each team are on the 2/3rd lines. Red team is there to assist opportunities to score, but do not have to be used. The idea is to develop a variety of scoring opportunities. You can award extra points for different types of goals and for different types of assists.

The development in action capacity for longer range passing comes from the distance of the practice. Red players are always free, if the GK or players at the back have time and space on the ball, they will usually attempt to find these players. The frequency of this action can be improved by awarding more points for a red player assist. This is just one example of how easy it is to develop action capacity within a contextual environment.

Skill

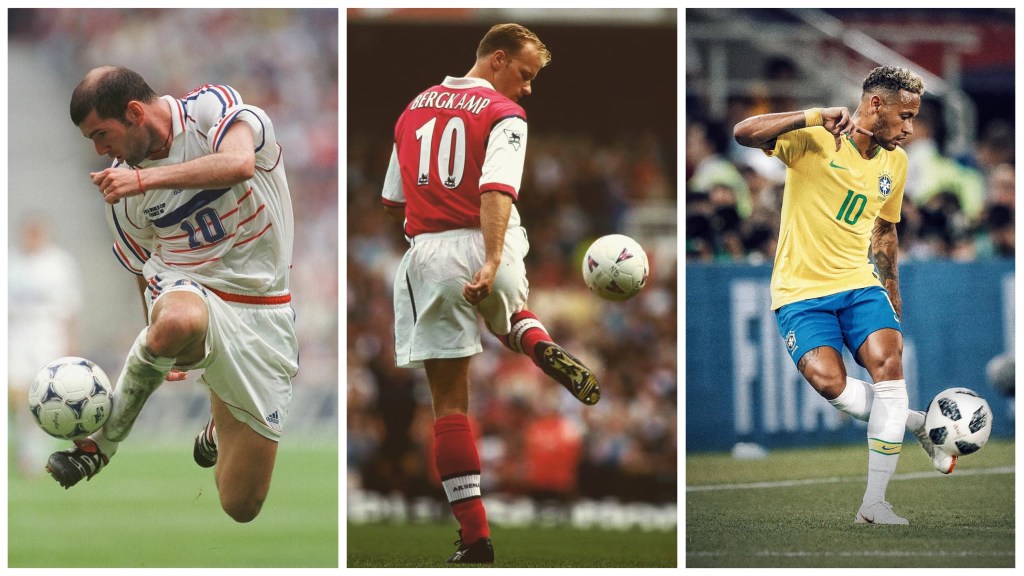

Here’s a hot take for you, our players today are less skilful than previous generations. Sounds crazy doesn’t it. In a world where technique is at the forefront of academy training and where we believe that our players are more technical than ever, I’m suggesting that players on a whole are actually less skilful. The likes of Messi, Suarez and Neymar are all but the last of the dying era of skill, as we usher in a new era, the era of efficiency. The era of the Machines. The artists of football are seemingly lost amongst stats, outcomes and results. Is developing our players to be more efficient, actually causing individuals to be less skilful?

If a young person today were to look at Zidane’s goalscoring record, they would think he was an average player. Those of us who saw Zizu play know there was something different about him. His level of skill and the joy he brought through variability. Look at all of his touches, goals, assists and dribbles. Every one, more different from the last.

Would Zidane have been a better player if he was more efficient? If we had streamlined his game and increased his statistical output? If he had waited for the ball to come to him, if he didn’t dictate the tempo of play, if he didn’t hold onto the ball?

Skill is the use of functional action to solve a problem. In other words, using a variation of techniques to overcome physical constraints (eg. athleticism), psychological constraints (eg. fear, confidence) and tactical problems. With this in mind, to standardise and isolate ‘technique training’, to perfect one specific technique, will not help your players become more skilful. The art in developing technique, is to improve the range of solutions to achieve a functional goal. The more the players are asked to search for answers using different techniques, the more adaptable they’ll become and the more skilful they’ll be.

But how will they improve on their aesthetic technique? Over time, whilst practicing in contextual environments, player’s will improve their consistency in varied techniques. The more they practice and use these varied techniques, the better they’ll get. The more they practice in context, the more they will be able to use these skills and techniques in a contextual performance environment. So maybe the view of more reps is right, but its more reps in context that’s the key.

Play

We would all agree that there has been a huge decline over the last few decades in child centred play. You only have to walk through the local park to see that pick up games are almost a thing of the past. And has the lack of unstructured play led to a decline in skill? The joy of park play is that there’s no one telling you what to do, you have to figure out how to win against your friends. As Legendary manager and FIFA’s current chief of global development, Arsene Wenger, mentions in a recent interview with the Independent:

Almost every academy in the country seems to spend time on ‘technical work’. The considered increase in technical ability since the 90’s seems to suggest that this technical work is and should stay as a pillar in the development of our nation’s players. But are today’s players that much more technical? If you go back and watch the best teams and players in world football through the ages, you will see hundreds of high quality technical outcomes. Are we truly being led to believe that Roy Keane, Zinedine Zidane and R9 couldn’t play in today’s game? As Roy would say, ‘do me a favour’.

The tactical side of the game has also improved significantly, as has the defensive side, meaning it’s harder to break teams down and score goals. It would seem that adaptable players are needed now more than ever. To add to this, the pitches that are played and trained on now allow more opportunity for passes to be made on the ground. Perfectly flat, no bobbles. Has all of this led to, not an improvement in technical ability, but an actual decline in skill? Have we substituted adaptability and skill for standardised pattern play?

What if the poorer playing surfaces of the 90’s actually meant you had to be more skilful as a player? More bobbles, more ball’s stuck in the mud, more aerial balls to control. More unpredictable problems to solve. Long passes were more frequent and are harder to produce accurately and to control. What we see when we look below the surface, is a high level of variability. So the question looms: is technical variety actually more important than technical repetition?

Now, I’m not suggesting we go back to long ball, ‘play into the channels’ football, but do I think that, in terms of skill, that our training has become standardised. Everything on the floor, in the same way. You hear it all of the time. ‘Back foot!’, ‘side on!’, ‘fizz those passes in on the floor! No bobbles!’. The question I pose is, has this linear standardising of football training, coupled with the decline in play, made our athletes less skilful? And how do we counteract all of these environmental and social changes to develop more variable and skilful players?

Perfection

Johan Cruyff famously said, ‘technique is passing the ball in one touch, with the right speed at the right foot of your teammate.’ Looking at this quote, the action of a one touch pass can never be the same. Do you need the technical repetition of a non-variable, one touch passing drill around cones/mannequins or do you need direction, opposition players getting in the way – defending a goal, team mates creating new gaps and spaces and consequence if you lose it? One replicates the conditions necessary to practice one touch passing, and the other does not.

The ball, gaps and spaces decided by opposition players and teammates, where you want the ball to go, the area of the pitch, conditions of the pitch, the constraints of the individual (height, athleticism etc.) and more will all play a part in a the perfect first time pass never being the same as the last. Football is highly dynamic and variable. It’s ever changing. No first time pass can ever be the same. So it’s time to ask ourselves the question: do we develop our players in variable, ever changing environments?

Majority of the training I see is around constant repetition of an action. Repetition after repetition: to repeat the same movement pattern again and again. Within this type of practice design, there is minimal if any technical variability. As we’ve now established that technical variability is more important than technical perfection, how do we look through this new lens to design our practices?

Repetition without repetition: The repetition of the search for a solution. Variability here is encouraged in the search for a functional solution to a set task.

Skilful Adaptability

Let’s challenge our perception on what we should be developing in our athletes when it comes to technique. Rather than expecting players to consistently reproduce the same action, let’s focus on our players being skilfully adaptive. It’s not so much the perfecting of a particular action, it’s having a variation of techniques to be adaptable. If you have an abundance of ways to do something, you should be able to solve the problem in a variety of ways.

Our Job as a coach is not to fill the players with our prescribed knowledge and movement patterns. They are not receptacles to be filled and it is not our job to fill them. Instead it is our role to create a dynamic environment where players are free to problem solve and it is our job to highlight opportunities to act (affordances) that they might have missed to do so. So how does this look in practice?

Ball Manipulation

Let’s start with ball manipulation. The first thing to understand is what ball manipulation actually is. Manipulating a ball on game day, is to move the ball in a variety of ways to keep it away from opposition players, or to move through, over and around opposition players into new spaces. So when our players practice, we need to make sure that this is replicated. But what should this look like?

When we think of ball manipulation we think of everyone with a ball – a great start. We then think of players touching the ball with different parts of their foot numerous times in a set pattern. Of course touching a ball multiple times is better than not at all, but unfortunately, this type of practice isn’t really related to the performance environment (game day). So how should we go about improving individuals ball manipulation technique within context?

The short video above is an excellent breakdown of why opposed ball manipulation is going to help develop your player’s manipulation of the ball and why isolated versions of ball manipulation practice aren’t. In the isolated practice, there is no stimulus (something that evokes a specific functional reaction) to act upon. In other words, there is no reason to manipulate the ball, with no stimulus to perceive and act upon, there is no relevance to the performance environment.

The idea is not more touches, but better touches. Quality over quantity. More of the wrong thing will not help your players improve. If you want your players to be masters of the ball, have a play with giving each of your players a ball and having opposition in the practice. This should create more variable and realistic situations for your players to solve.

Turns and Beat the Man Moves

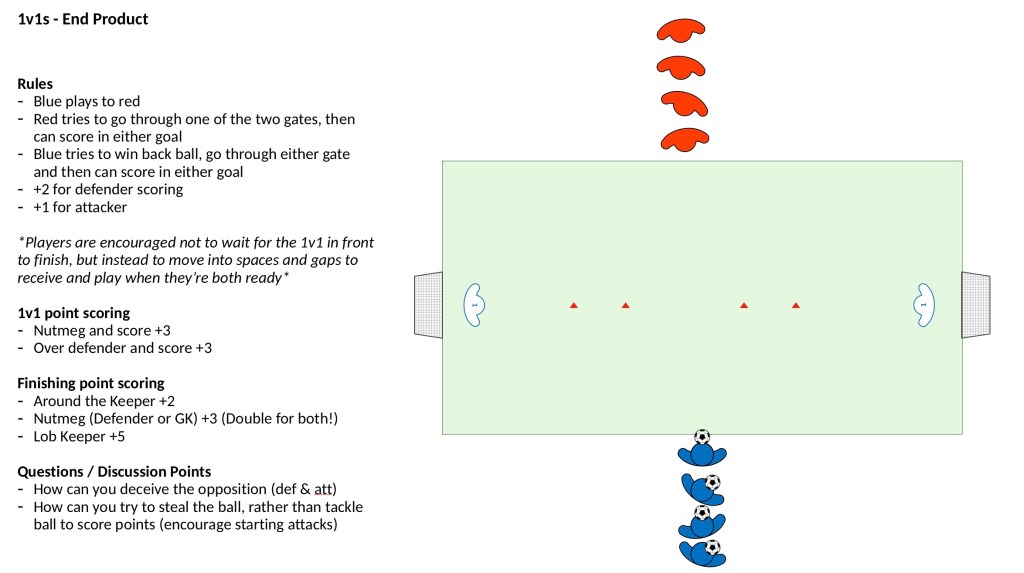

In the above practice, players are encouraged to beat an opposition player to move through one of two gates. When they do so, they can score in either goal. The option of two gates leans into the player on the ball using disguise to off balance the opposition player. And the option of scoring in either goal leans into using disguise and functional turns to get a free run at one of the goals.

‘But if they don’t know how to do a Cruyff turn, how will they do it in the session?’ The answer is that they might not and that’s okay. More importantly they might turn in a way you’d never imagined possible before. And that’s the key, allowing them space to be creative, you can’t force creativity into players – they must be given room to express themselves functionally.

It’s not about which skills they use, more so if they are completing the task in a variety of ways. The important information is for them to perceive the available space, the speed and trajectory of the incoming defender and to score a goal. If they do this, they can use any skills and turns they come up with in the moment.

Combinations/Passing Patterns

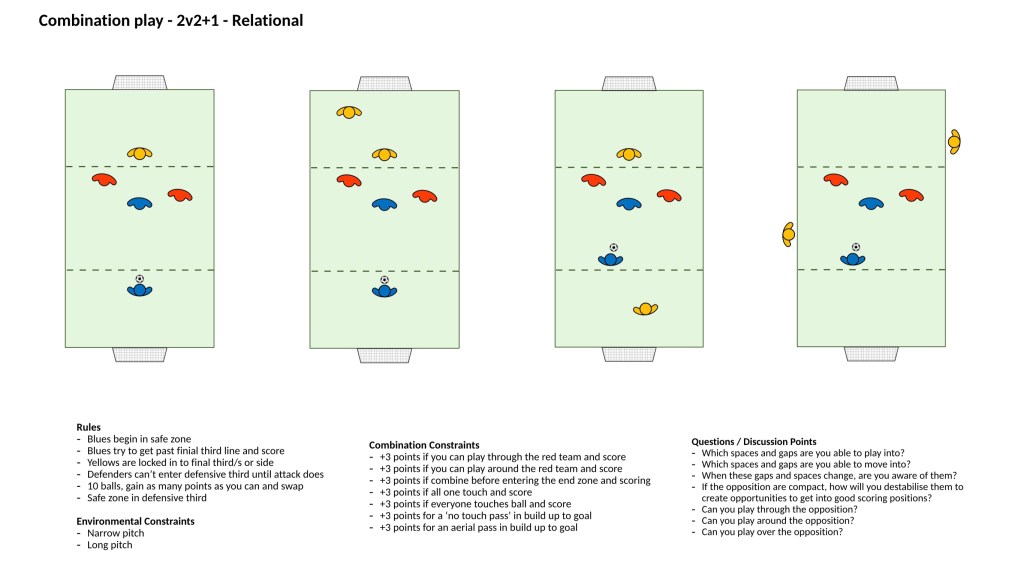

The above practice is a constraints led approach to combination play and an alternate to traditional pattern play. Players are encouraged, because the pitch is narrow, to combine with each other, and find solutions to move the ball to the final third and score a goal. Encourage the players to look for emerging gaps and spaces and ask them to move the ball through, around and over into them, and then to move into new emerging spaces and gaps themselves.

You can add extra points for anything you believe the players are lacking eg. +3 points for an aerial pass in the build up to a goal. Or +3 for a no touch pass. There are more ideas like these on the session plan and should not all be added at once, but gradually depending on your observations for what the group need.

Third player runs will always emerge when there is the use of a target player that can’t score, as the task set means they have to support the target player when they get the ball. You do not need to force a third player run pattern into existence for it to work on game day. You don’t even have to use the phrase ‘third man run’, just ask the players to look for gaps and spaces to support players ahead of them. They will do the rest.

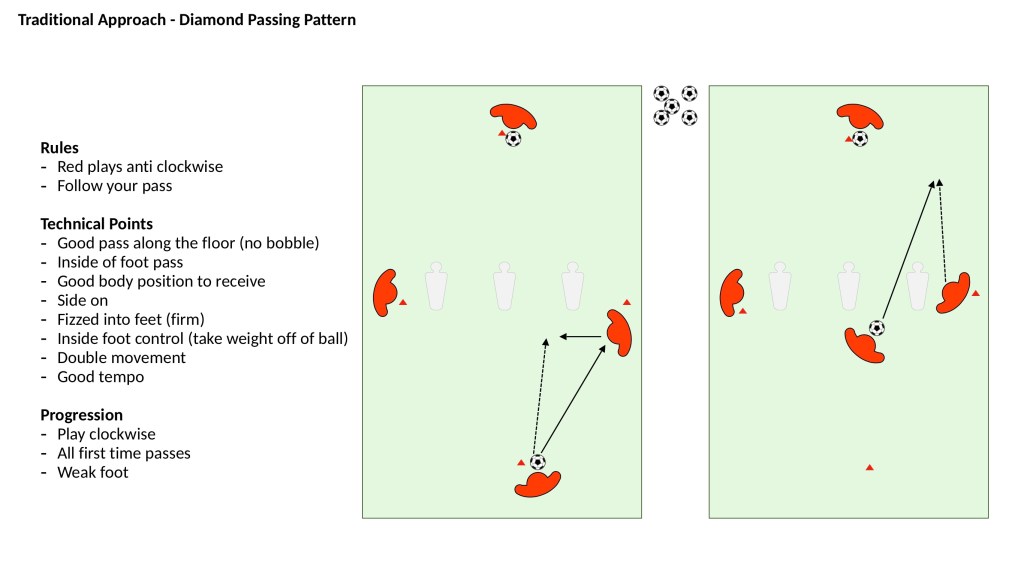

In traditional pattern play practice, you will see practices like the one below:

The passing pattern practice above has a number of problems when we look through the lens of technical variability. Lots of touches? Yes. Lots of touches in context and in relation to the game? No. There is no nuance in which to change the style of pass you might need to progress the ball, no understanding of relative timing and space and, because of the lack of stimulus, little to no variation in techniques to achieve the task.

The usual justification for this type of practice is the amount of repetition and it’s ‘all about the detail you put in’. The skill of the coach is shown through what he asks his players to imagine. However, if you’ve got a team there, ready to practice, why imagine when you could allow them to actively experience the relative information themselves? This type of practice seems to be more about a coach showing their knowledge of the game, rather than developing the player’s knowledge in the game.

If you want your players to notice opportunities to act within the performance environment, this type of practice is by far the least likely of the two to help them. We can be far more skilled in our design of the environment and task. Rather than force the action, let’s look to design the opportunity to act, allow the players to experience and explore these opportunities.

Receiving

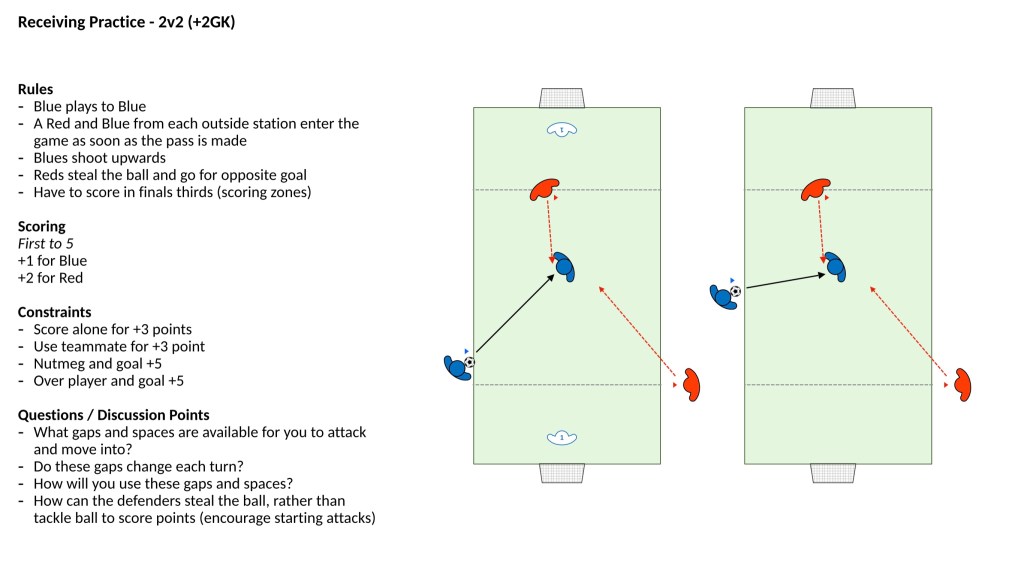

Receiving is not just the ability to receive the ball side on, back foot. There are an infinite amount of ways to receive a ball, and this all depends on the opposition and teammates creating new gaps and spaces to play and move into. The above practice is a constraints led approach to receiving. The players start in pre determined positions and as soon as the ball is played, everyone is free to move. You can add as many players to this as you want, and even let it develop into a match, with this as the kick off/restart.

The beauty of this practice is that even though the starting positions are the same, the defenders will adapt to stop the attackers in different ways every time the game is restarted. Therefore there is a large amount of variability that the attackers have to adapt to. It’s cat and mouse, the defenders will defend, the attackers will adapt, the defenders will then adapt to the attackers and so on. Receiving is all about awareness and adaptability and this practice is full of both.

Rather than forcing your players to receive the ball front or back foot, ask them to find a route to goal. Challenge them to do this on their own or with the help of their teammate by adding more points for each. Variable techniques will emerge with them attempting to be functional. The starting positions can be changed, ask the players to move their starting positions and see what different problems this creates for both sides.

Quality, not Quantity

Lastly, some coaches may suggest that the amount of repetitions or the actual amount of touches is why you should use a traditional approach to develop technique. However, I would rather a really great technique to be applied ten times in context, than to force 100 touches out of context. We should look for Quality not quantity.

We are obsessed with the idea that more is better. And maybe Malcolm Gladwell and the 10,000 hour rule is partly to blame. I would consider reading David Epstein’s Range: Why Generalists Triumph In A Specialised World. Epstein’s work brings into consideration that with very few exceptions, 10,000 hours of the same thing doesn’t lead to mastery, in fact, playing a variety of sports will lead to more unique movement solutions.

If we want to develop the brightest, most creative and innovative players in world football; we need to develop their ability to assess and exploit space in their own individual ways. And remember, it is not repeating the same action again and again that will improve our players, it is repeating the search for an action.

Variability in technique is what makes a footballer ‘technical’. With more variability, there are more keys to attempt to unlock the safe. Technique is not what we think it is, it is not the search for technical perfection – more so the search for technical variety.

Let’s stop the obsession with making our players more ‘technically efficient’ and start taking steps to help them become more skilfully adaptive.

I totally agree with your proposal. Technique doesn’t make much sense if it’s not applied to the game. However, I don’t think we should completely discard analytical training. As coaches, we should be able to introduce players to game situations (of their choosing) through their imagination.

Regarding ball mastery, it’s clear that it serves more than just coordinating body movements, spatial awareness, and striking the ball. Still, I believe it’s important to promote it because it gives us an idea of the time the child/player spends with the ball, a fundamental aspect for improvement. Encouraging it motivates the player to spend time with the ball, whether against a wall, with their dog, with a goal, etc.

Some argue that street football is fundamental for creativity because it’s a “free game.” I argue its utility lies in the significant amount of time we spent playing football or watching our friends, some older than us, play. It’s a valuable experience.

LikeLiked by 1 person