In 2011, Thomas Müller gave an interview on a German talk show, where he was asked by the host to describe his role on the pitch. He responded with the word ‘Raumdeuter’. While not particularly strong, fast or technically gifted compared to other players of his calibre, this newly coined description of Müller’s role characterises a type of player unable to be seen by the untrained eye. It would seem even an experienced professional would struggle to pinpoint what makes Müller great. Pundits and coaches alike seem unable to fully understand the Raumdeuter’s elusive traits and one simple question arises: do we value what we can not see?

Our mission is to search, explore and understand human development in football. We will look to connect science, theory and practice. We will navigate the winding road of development together, unpacking the myths and truths of the football world. We will bring together the experience of industry professionals and new ideas from the pioneers of youth development. We will discern both opinion and fact, successes and failures, past, present and future ideologies; all in the name of constructive discourse that will evidentially lead us to learn and improve, and create an environment where our players can thrive.

And in true, Raumdeuter style, we will look to uncover the secrets of what makes people great within the game that we all love.

the Raumdeuter is here to create a positive discourse among all coaches, players and football lovers from all over the world, we hope you enjoy and actively encourage you to challenge any ideas conflicting with your own, regardless of what level of the game you find yourself to be a part of.

Rethinking the Rondo: The hidden cost of positional practice in football development

Rondo, rondo, rondo…

The rondo, a training concept employed by nearly every coach from grassroots to the pro leagues. We’ve all used them, I have and most likely, you have too. Gaining worldwide popularity after Pep’s 2008-2012 positional Barcelona team, the rondo has been central to the positional game ever since.

Fixing players to specific positions, mirroring the structure of a positional game model, and encouraging quick, short passing against limited opposition clearly has its benefits in a well structured positional team. However, as the game continues to evolve, we must ask: what is the cost of such conformity when it comes to the individual development of our players? And are there alternative approaches that offer players greater freedom? Approaches that allow a broader, more complete picture of the game?

Xavi Hernandez, Barcelona legend and former head coach, reflects on its foundational role in the club’s style:

“Our model was imposed by Cruyff … It’s all about rondos. Rondo, rondo, rondo. Every single day. It is the best exercise there is.”

Johan Cruyff himself, perhaps even more famously, expressed the value of the practice by saying:

“Everything that goes on in a match, except shooting, you can do in a rondo.”

As we drift ever closer to netball-like constraints within a sport that is inherently dynamic, the development of our players demands far more than static positioning, structured passing and rehearsed pattern play. If we maintain this trajectory, positional practices like the rondo will continue to quietly erode expression and marginalise uniquely talented players whose skill in perceiving, interpreting and acting through dynamic interactions allows them to generate solutions in moments where structured play alone cannot.

As the game evolves and players are asked to reclaim their agency—adapting, creating and solving problems in real time. Where does the rondo, and positional practice in general, fit in the development of perceptive, self-organising and adaptable footballers?

The Limits of Control

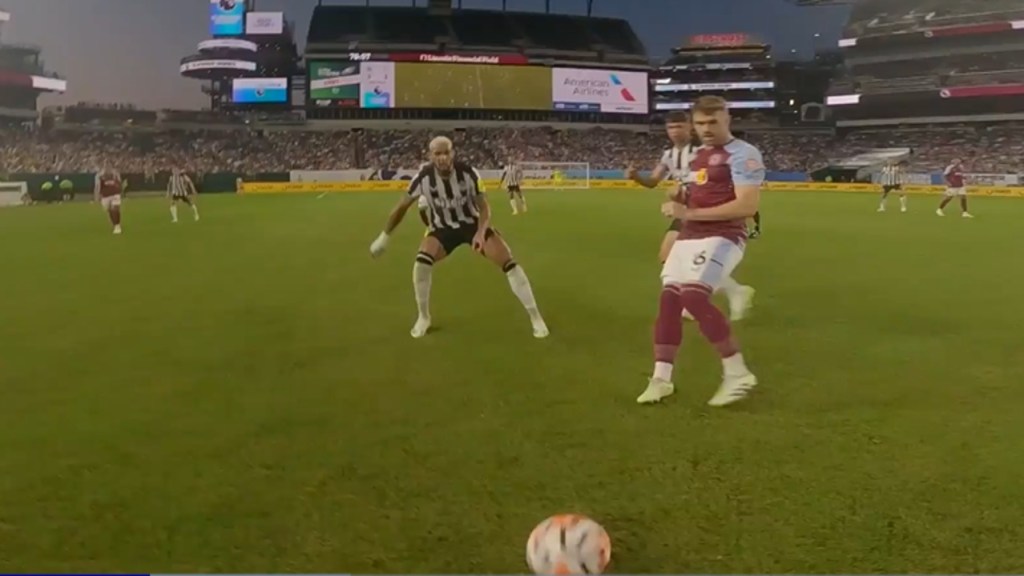

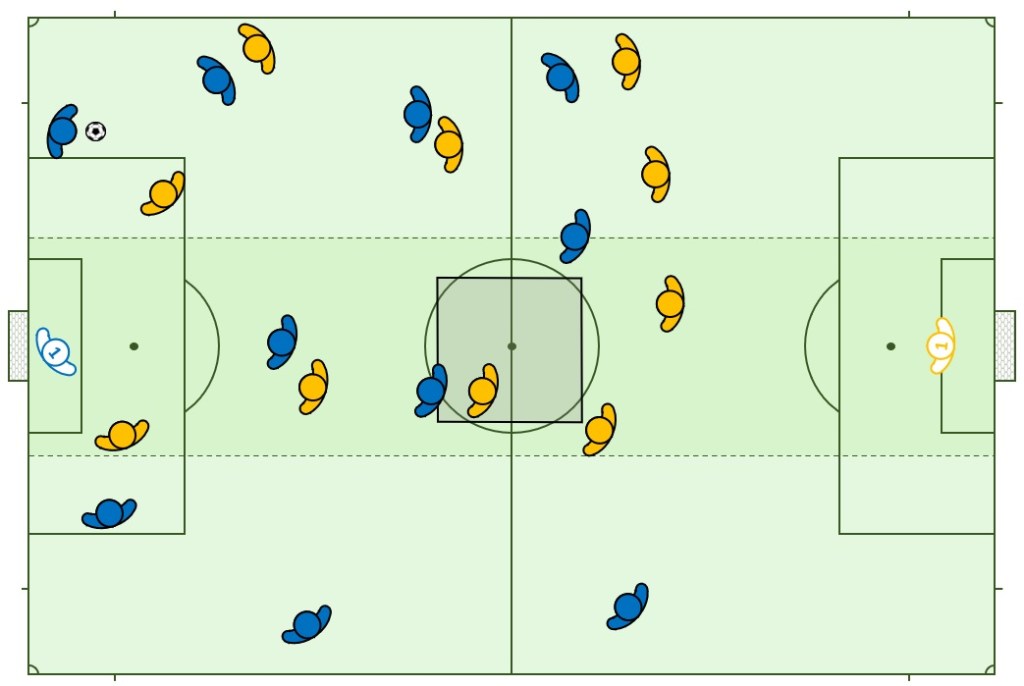

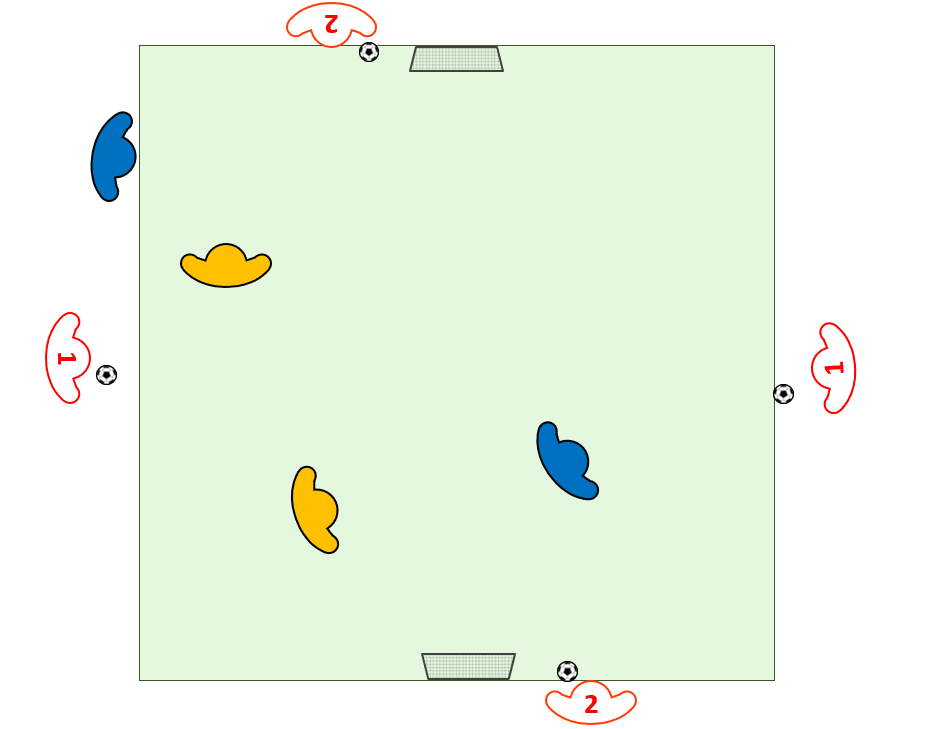

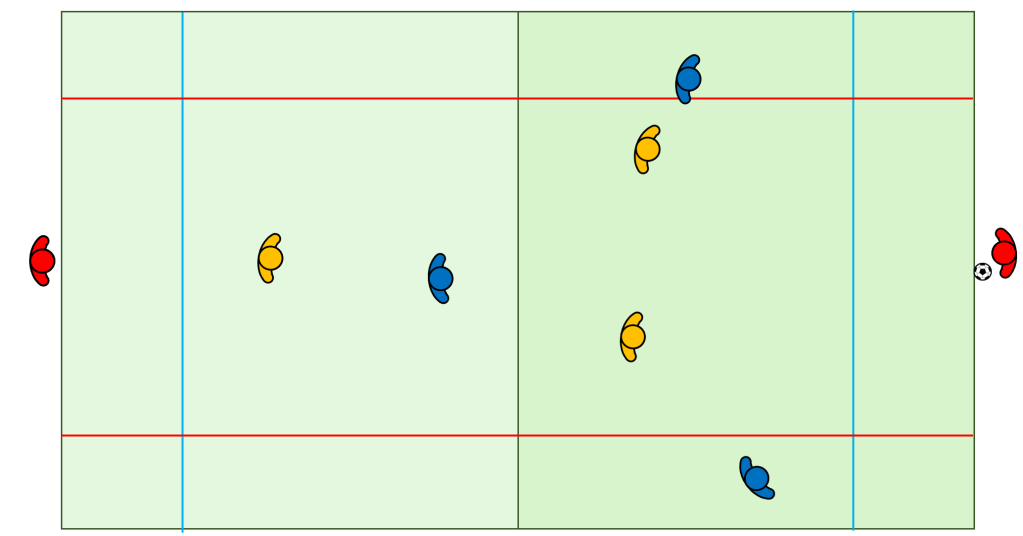

The classic rondo, as seen in the image above, usually positions players around the edge of an area, with one or more in the middle attempting to regain possession.

Rondo’s do have some benefit: designed to improve quick, short passing, anticipation, and a degree of realistic defensive pressure. In possession our players must read and play around the opposition; out of possession, they must anticipate and intercept. Even allowing creativity and disguise, such as, players faking passes or pressure to mislead the opposition.

However these benefits come with significant limitations. Reducing freedom of movement not only diminishes the quality of deception—as players only have pre-defined options from which to choose their pass, but their overall perception is constrained. Never needing to scan 360 degrees, fixed positioning leads to our players losing the need to pick up new information. Ultimately, the rondo directly contributes to diminishing the need to observe and make decisions in an ever-changing environment.

And despite Cruyff’s admittance, shooting isn’t the only skill absent in positional possession drills. Dribbling and ball carrying are rarely encouraged. When positional exercises prioritise structured possession, players are subtly conditioned to avoid the use of these skills all together, limiting the development of those abilities which allow them to break lines, create space and exploit opportunities in unpredictable ways, when these are integral skills for high level possession play. In short, the rondo reinforces conformity at the expense of adaptability and individual expression.

More subtly, and perhaps insidiously, the rondo rewards obedience. Success within the practice is defined by strict rules, maintaining your position, body shape and role. Players who comply are praised as being ‘coachable’; and players who deviate are corrected. Players who follow the movements the coach instills are considered ‘intelligent’, whereas leaving a position to search for new solutions; carrying the ball into unfamiliar space, or disrupting the team structure, is often framed as ‘poor play’, rather than exploration.

Over time, this silently conditions players to associate ‘good football’ with doing what they are told. Rather than discovering what the game is asking of them, and how to answer in their own unique way. The long term cost is significant: players stop searching. They wait for instruction. Creativity becomes ‘risk’, and agency is replaced by compliance. This is not a failure of the modern player—it is a predictable outcome of the environments we design.

And this is the core flaw of positional-led practice, regardless of area size or team configuration—the aim is clear: ignore unique skillsets and relationships between players in favour of minimising mistakes. Every player must perceive the game in the same way and act upon it accordingly. This is not football development. It is simply conditioning our players by imposing one single perception of the game.

Positional practices like the rondo do not merely condition a player tactically, they condition a behavioural state. When repeated daily, this becomes the player’s default state, shaping not only how they play, but how they think.

We must be careful when designing practices to ensure we do not condition players into something they are not. True development is about empowerment—empowering players to be who they are. Taking this away destroys any chance of helping players reach their full potential; for it is unreasonable to expect someone to realise their potential by becoming a vision from another’s mind.

From Predictable to Perceptive

Some argue that rondos are merely warm-ups, designed to ease players into a session or a game. While they can provide a relaxed entry into the training or performance environment; restrictive, positional practices do not prepare players for the chaos and unpredictability of the game. If anything, a warm-up should be harder than the game itself.

They shouldn’t gradually warm up perceptual cognition like cold water in a pan; but like food hitting hot oil—sudden, intense and awakening the senses. Players should be alert, perceptually and cognitively primed and biomechanically ready to seek and find unique solutions.

These practices should not exist just to prepare the body, they must prime the mind. Beginning a session in static, organised and predictable environments places players into a controlled behavioural state before the game has even begun. Movement becomes cautious, decision-making becomes conservative, and responsibility is subtly outsourced to the structure. When players are then asked to perform in chaotic, high-speed match environments, we should not be surprised when they struggle to adapt. We trained them to be compliant.

In short, warm-ups should be extreme versions of the game. (It is important to clarify that age specific physical preparation remains essential to reduce the risk of injury before any practice.)

We can also rethink the order of session design to maximise learning through play. Traditionally we design our sessions with a slow and small area warm up, a skill practice with smaller numbers, and then leading into the main game-like practice. The problem here is similar to positional exercises—we are conditioning the players to play slow or in reduced area size and then ramp up the intensity and area size as we go along. This, again, is not confluent of the performance environment.

There are, however, alternatives. Starting with a game, moving into a focused practice, and returning to the game can be highly effective. This “whole-part-whole” approach, widely referenced in theory, can be applied in a way that challenges perception and adaptability. Beginning with the game immediately immerses players in complexity and unpredictability; the practice then provides space to explore and refine solutions, before returning to the chaotic, real-world context of the match. This structure keeps players cognitively engaged and perceptually primed throughout.

And why not run sessions where the same game lasts the whole session, with multiple constraints and adaptations applied throughout. Players remain cognitively and perceptually challenged, constantly problem-solving and adjusting, without ever becoming passive or predictable. By embracing extremes and unpredictability in both warm-ups and practice, we prepare players to act perceptively, creatively, and decisively in the moments that matter most on the pitch.

Finally, for true 360-degree perception in practice, players need to experience a constantly changing environment, which the traditional positional practice does not provide; as they are far too stable and controlled. While positional practices do offer some benefits, as noted above, there are other ways to combine tight spaces, quick decision-making, deception, and perceptual awareness—all without conditioning players to expect fixed patterns or limiting their freedom of movement and reinforcing predictable decision-making.

Principles > Instruction

If our aim is to develop perceptive, adaptable and self-organising players, then practice design must move beyond instructive game models and positional drills. Instead of prescribing where players stand, we should design environments that demand continuous searching, adjustment and interaction.

This means building practices around principles such as:

– No fixed positions

– No guaranteed passing options

– Direction that appears and reappears

– Numerical balance and imbalance that constantly changes

– Space that expands and collapses

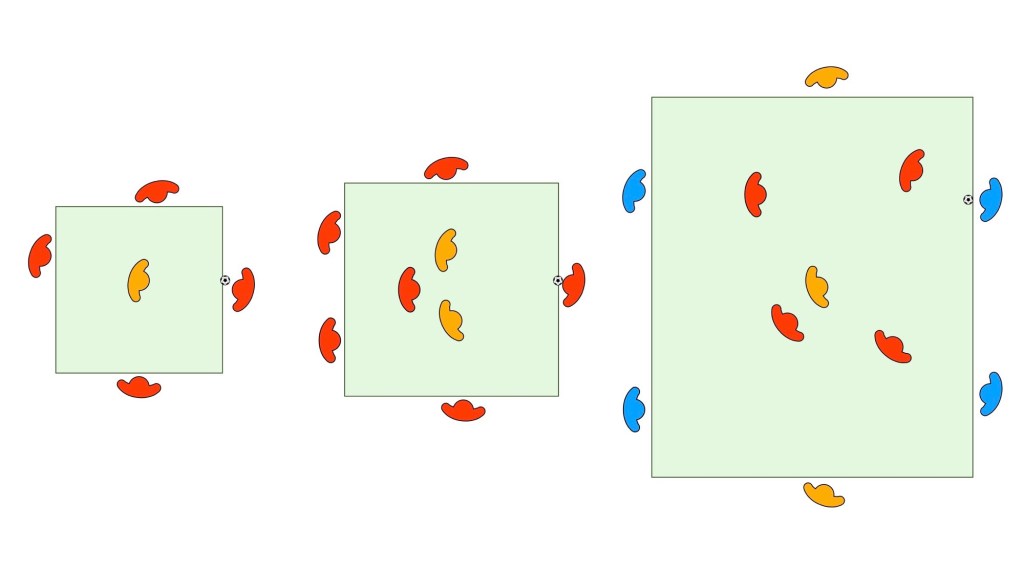

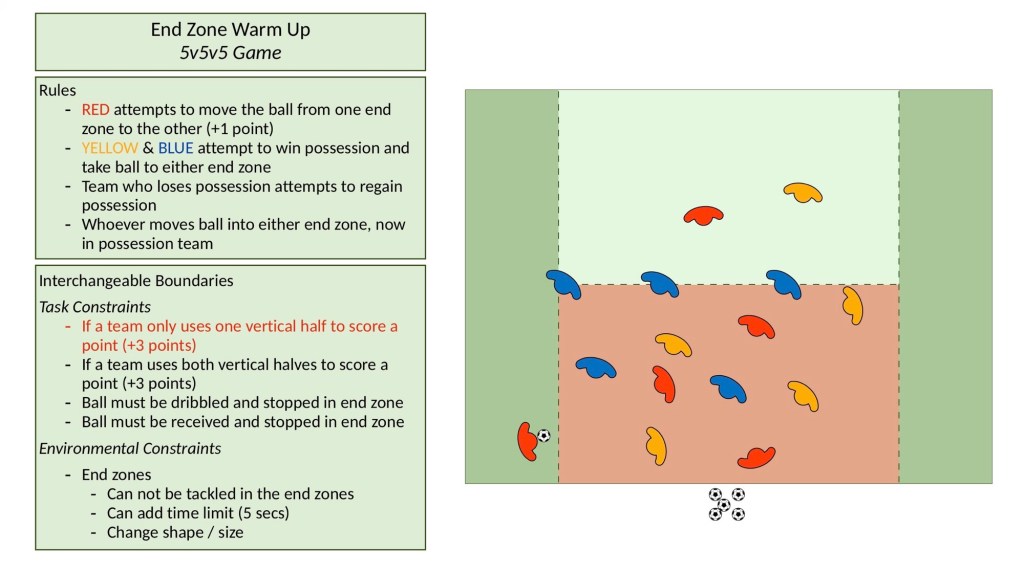

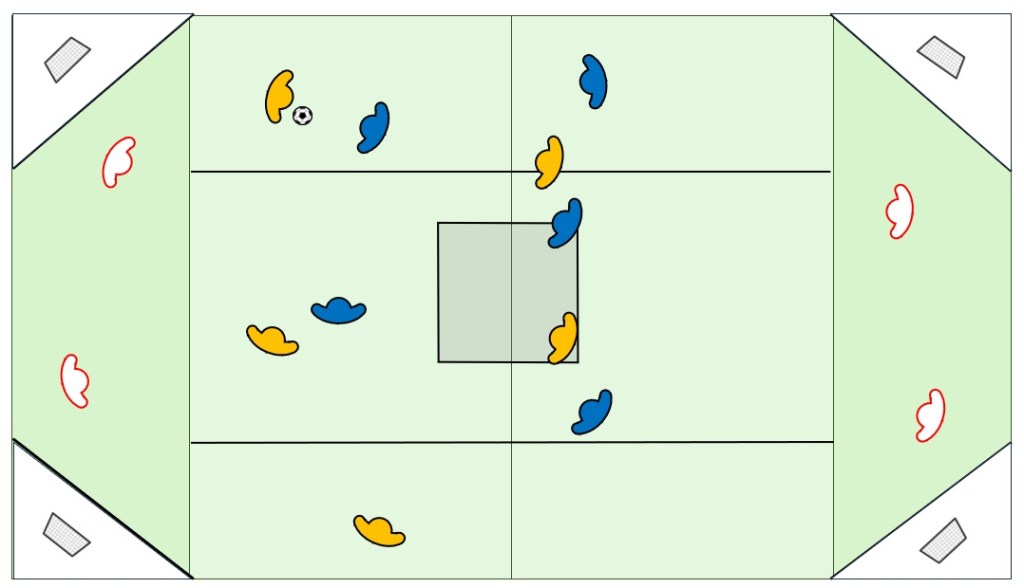

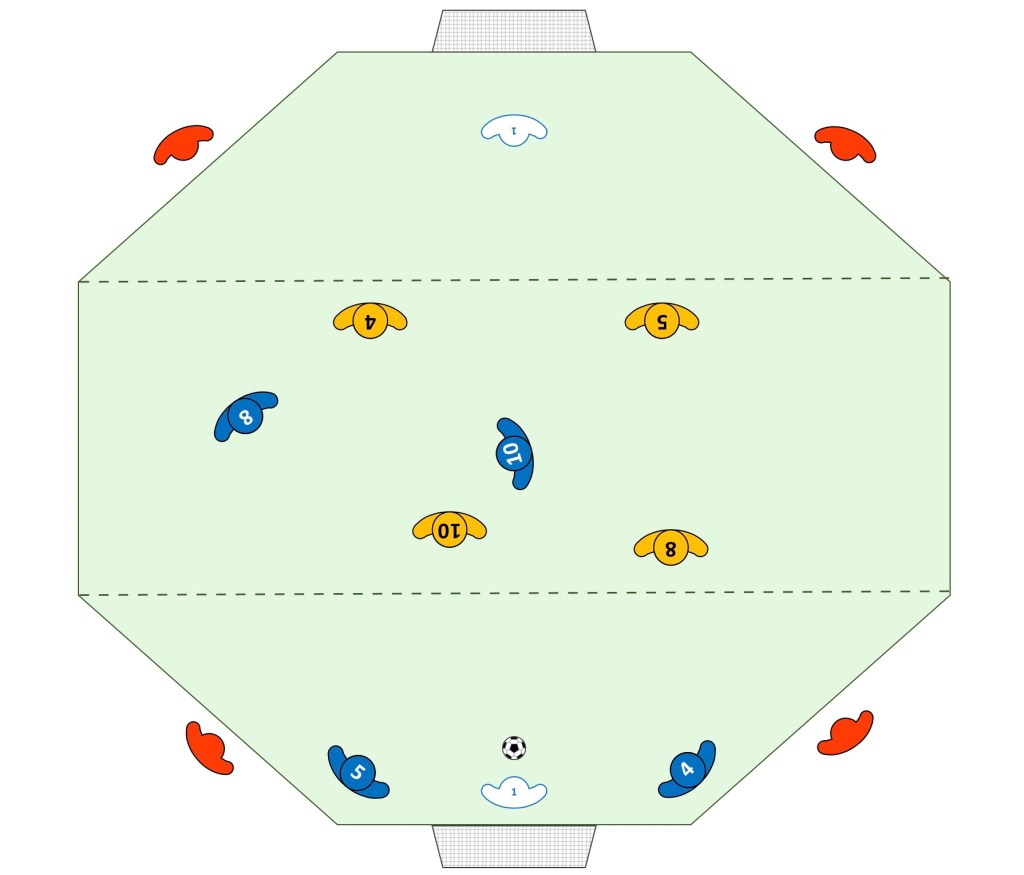

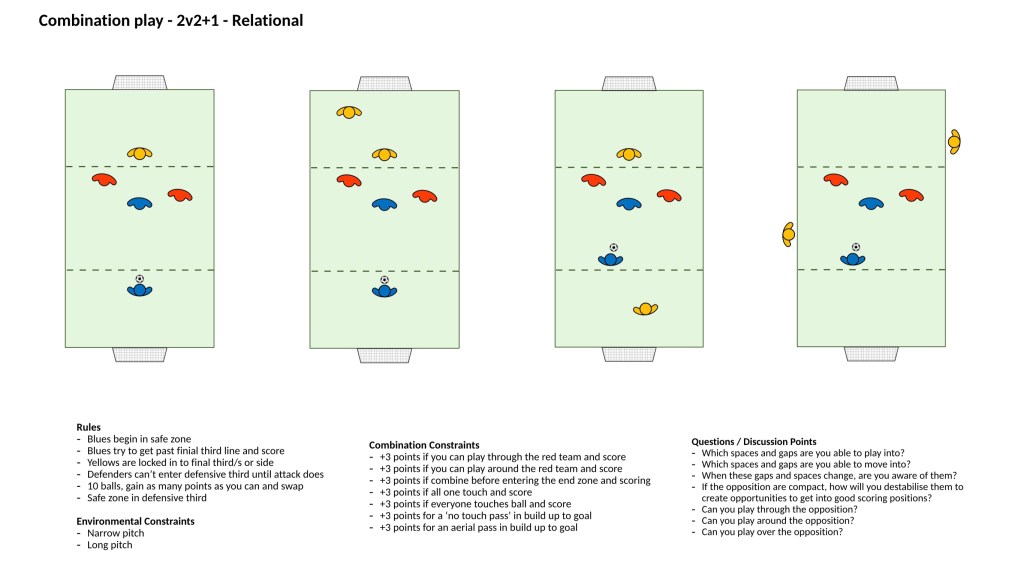

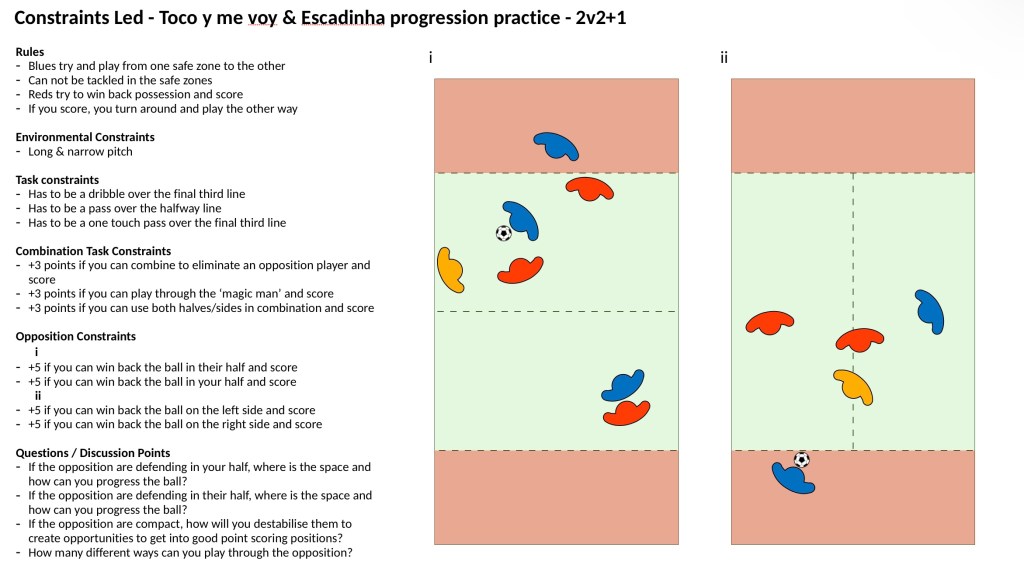

Below, is a three team practice that can be used as an alternative to a positional practice or warm up (all constraints are to be adjusted, added or removed depending on what you observe—and be sure to allow periods of free play):

Three teams share a common space, but the boundaries, objectives and numerical relationships are never fixed. At times the area expands, inviting players to carry the ball foward; moments later it compresses, forcing tight combinations or individual escapes. Direction can emerge through scoring incentives, then disappear entirely, requiring players to reorganise possession without reference points.

Players are encouraged to abandon roles in search of solutions; dropping in deep to overload, stepping forward to break lines or carrying the ball when no pass exists. No player owns a position for long, and no solution remains optimal for more than a few seconds. The game organises itself, and the players learn to organise with it.

A New Lens

If we are to support the development of creative, unique and adaptable players, we must design everchanging environments rich in opportunity. We need to give players the space to explore, make decisions and discover their own solutions.

Amid a sea of control and predictability, it is up to us as coaches to break with tradition and design practices in which players can truly evolve. There is so much more out there when we stop looking at development through a positional lens and begin to embrace the chaotic nature of human development.

If we continue to prioritise control over curiosity, structure over exploration, and compliance over perception, we should not be surprised when players struggle to adapt beyond the environments in which they were conditioned. Development is not about producing identical interpretations of the game, but about nurturing individuals capable of navigating uncertainty with composure and intent.

Maybe it’s not time to rethink the rondo after all, maybe it’s time to let it go.

Boxed in: How the thirds of play impact creativity in football development

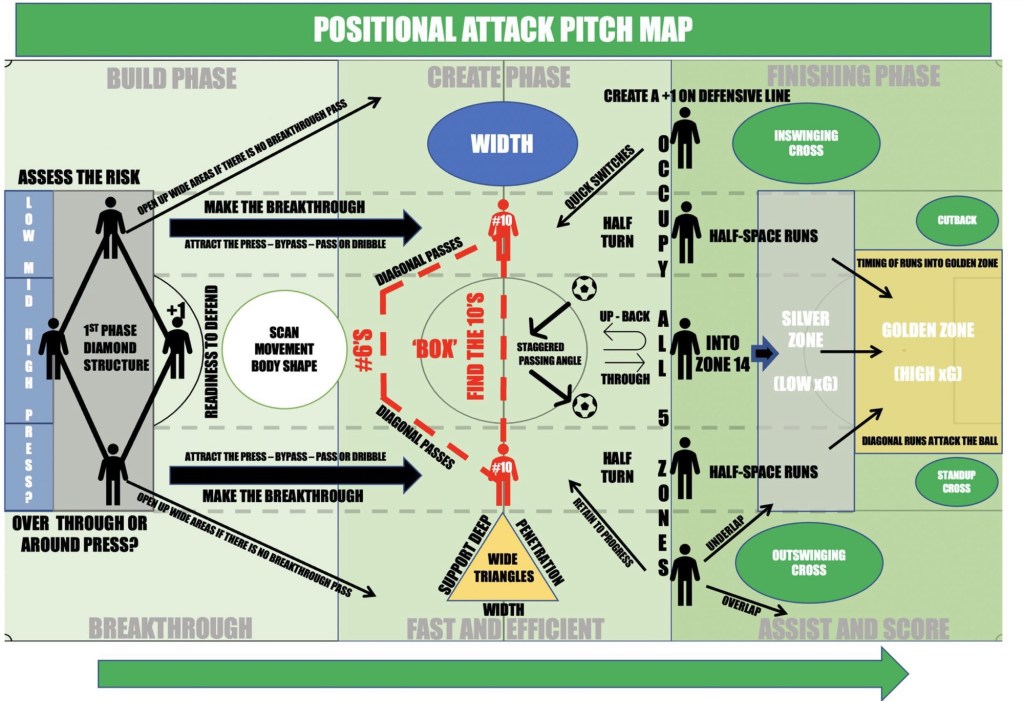

If you’ve ever worked in football development, you’re probably familiar with the concept of the pitch divided into thirds: Build, Create, and Finish. These three words have been drilled into us for decades, forming the backbone of countless game models, curriculums, and footballing philosophies. Often viewed through a positional lens, even the England DNA framework leans heavily on these principles.

But is this approach actually stifling the development of our young players?

The idea that a player can only “create” once the ball reaches the midfield or “build” solely within their defensive third is, in my opinion, deeply flawed. It curbs the potential of creative defenders who thrive on making bold plays from the back, as well as attackers who relish opportunities to contribute deeper in the field.

Take a closer look at most academy sides in England, and you’ll see defenders endlessly recycling possession in their own third, missing clear opportunities to bypass lines and exploit space. The rigid adherence to this linear model does more than limit creativity—it dulls the game.

If we must simplify an inherently complex and dynamic game for ease of understanding, we should rethink the current model. A player’s decisions shouldn’t be dictated by where they are located on the pitch, but by the unfolding realities of the game itself. Players are often given one set of answers through a positional game model, and are unable to explore the game in their own unique ways.

As coaches, we need to recognise the difference between how we see the game and how players experience it. Development isn’t about forcing players into our perception of how the game should be played and if we truly want to produce world-class players and coaches, we must begin to see their version of the game, through their eyes. We must view them as individuals—not as positions within a rigid game model.

The Price of Conformity

Most of a coach’s time on the pitch seems to be spent creating patterns and helping the team to build an attack. But every game model I’ve seen misses one crucial step: Identification. Who are the individual players on my team? Who are the individuals on the opposing team? And how can we exploit weaknesses to score and win the game?

This integral step is glaringly absent from most game models and philosophies. Instead, it’s replaced with a rigid, fixed team identity that takes little account of how the opposition plays or what the unique qualities of individuals on both sides bring to the game.

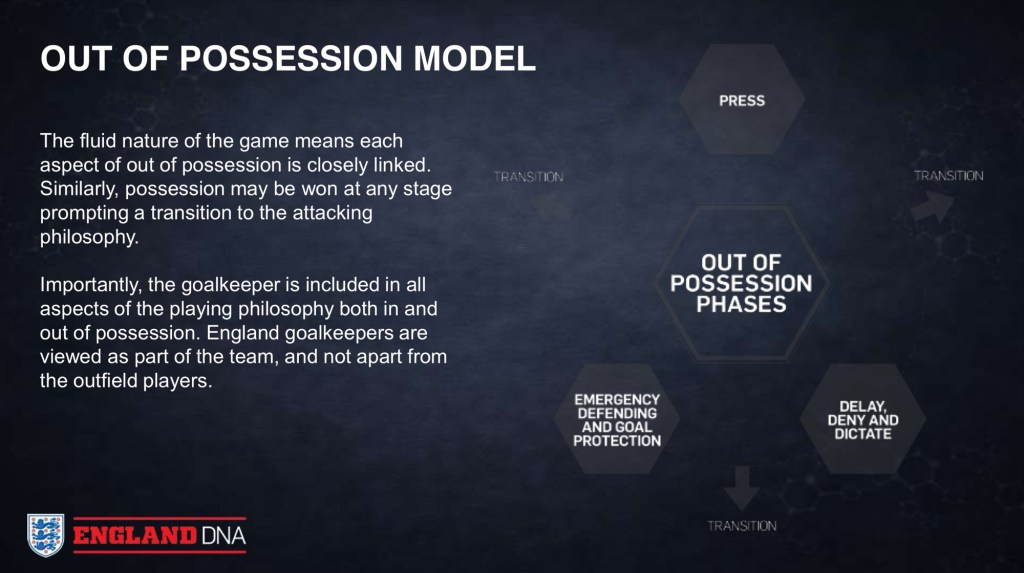

Take, for example, the England DNA model for coaching players out of possession. The first thing you see is press. All good and well—until a player like Harry Kane comes along. So now what? These linear breakdowns of football philosophies lead to forcing square pegs into round holes. If this structure can’t support the qualities of England’s all-time leading goal scorer and current captain, what other talents are slipping through the cracks?

We’ve all heard the excuses: “He can’t get around the pitch,” or “She can’t press.” How many exceptional footballers have had their development stunted simply because they didn’t fit into a rigid game model? On the flip side, how many players have been given opportunities—not because they’re great footballers, but because they can run around and press, just as the game model demands?

These frameworks destroy more than they create. It’s painful to think about how many quality players with unique skillsets we may have lost.

So how do we go about making sure we support the development of all types of players, not just one type created by rigid game model.

The FA’s England DNA ‘Out of Possession’ Model

Build, Create, Finish

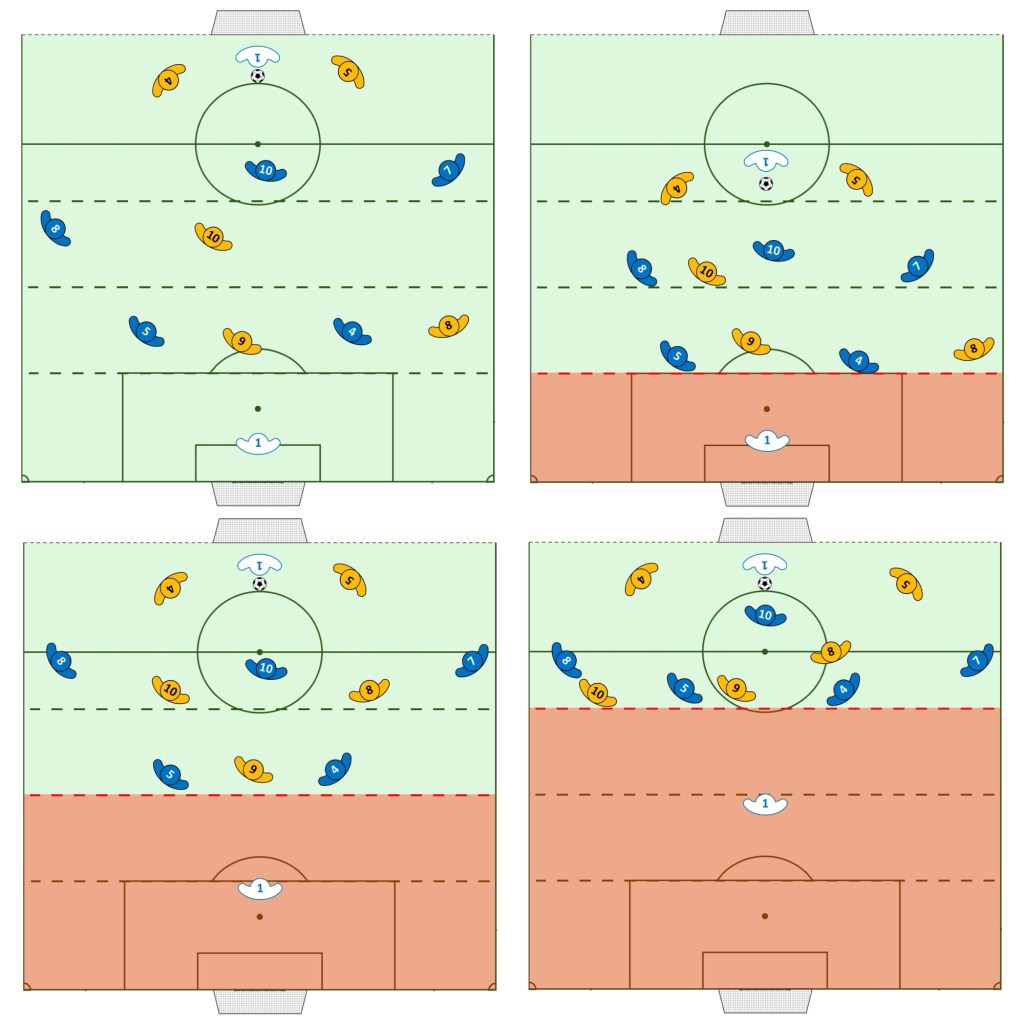

One way we can do this is with our session design. When we typically design a practice, we will look at what we want the team to learn, and fit an area size which is deemed relevant—often using relative pitch dimensions. Now this seems logical, however if we look closer, this will often lead to players attempting to exploit static space in the same ways over and over.

What I suggest is to constantly move the area boundaries of the practice. So players have to continuously problem solve working in different spaces on the pitch. When we say that the pitch is a particular size, so we’ll work in a similar area size in training, we forget that there are often moments in the game where, despite the full size of the pitch, the full use of this area is not available for the the players around the ball to use.

The game is so dynamic and variable that spaces open and close continuously, so with that in mind, do we recreate these ever-changing spaces in our training sessions?

I would also advise moving away from realism in this aspect and begin to create extremes. This is to exaggerate the space, or lack of it, to the players, then our players will need to quickly reorganise, constantly finding new solutions, and in turn, using more of a variety of skills to overcome the problem of ever changing space.

Despite this not being realistic in terms of a static pitch size, it is realistic in training the ability to adapt to ever changing spaces.

Alignment or Agreement

When a coach first steps into a professional academy, they’re met with a philosophy and a game model. They’re told that all teams must be aligned in their style of play—to all look the same. This, however is not alignment, but agreement. If we are truly and holistically developing individuals, no team should look the same.

Every team, every age group, and every individual brings something unique to the game. The first step should always be identifying who your players are: How do they like to play? Who inspires them? What makes them unique?

Once we understand that, we can build teams around these individual strengths. Each team would become unique. Each player would feel seen and valued, developing into the best version of themselves—not a limited version molded to fit the system.

Players should also learn to evaluate their opponents: What are the weaknesses in the opposition? How can their strengths exploit those weaknesses? Imagine shifting from “play through the thirds” to “Their back line is high—how can we exploit that?”

The game is not simple; it’s complex. Yet, we often teach players a linear, oversimplified version of football instead of equipping them to analyze and adapt in real time. As coaches, we owe it to our players to truly know them: Who are they? What do they love? How do they play? Who are their role models?

Only when we embrace their individuality can we develop them into the best versions of themselves—not the watered-down versions we impose through rigid systems.

When building a practice, we must not aim to develop players who play one particular way and use a limited set of skills, but look to develop adaptability and allow for a wide variety of skills and techniques.

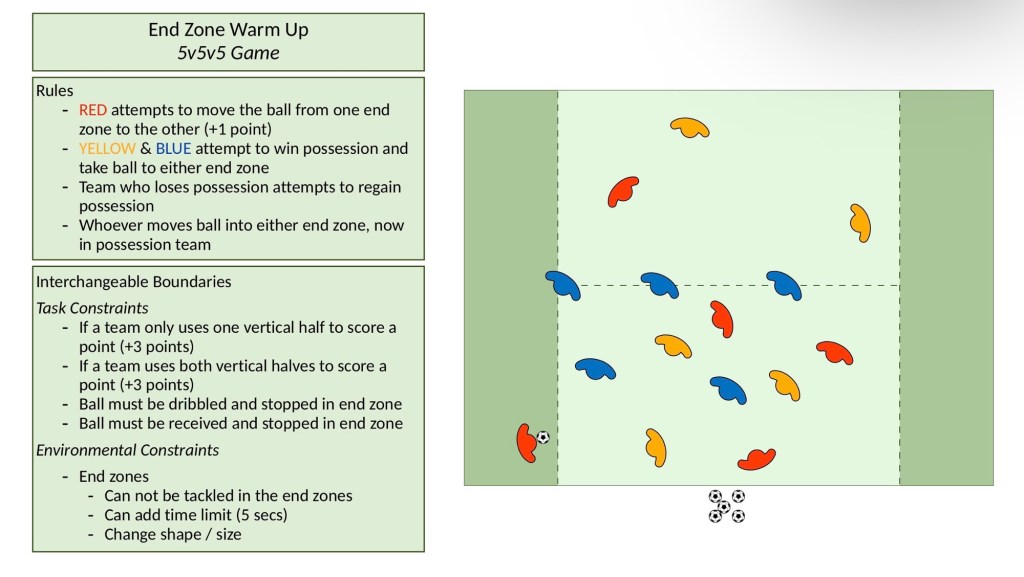

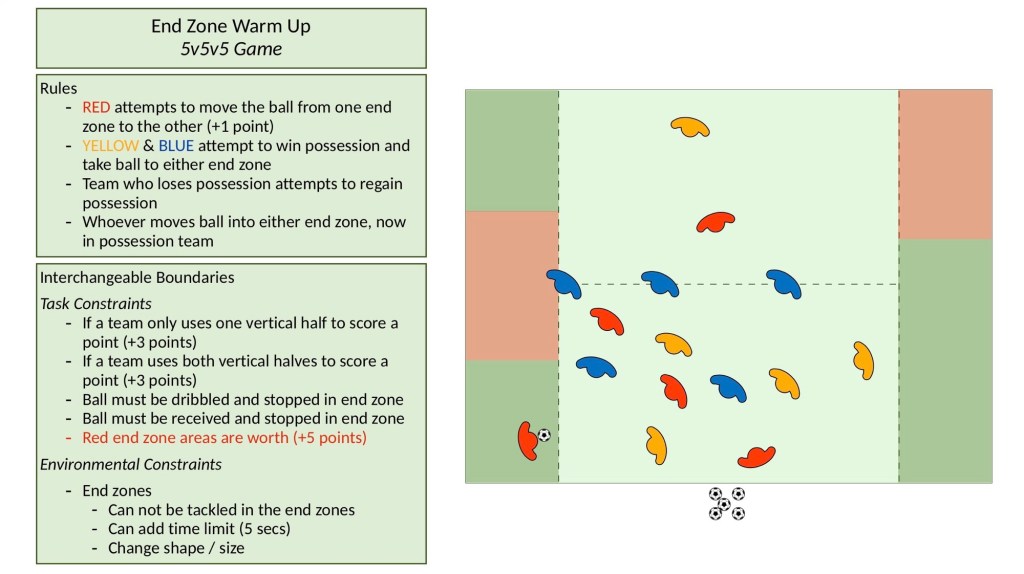

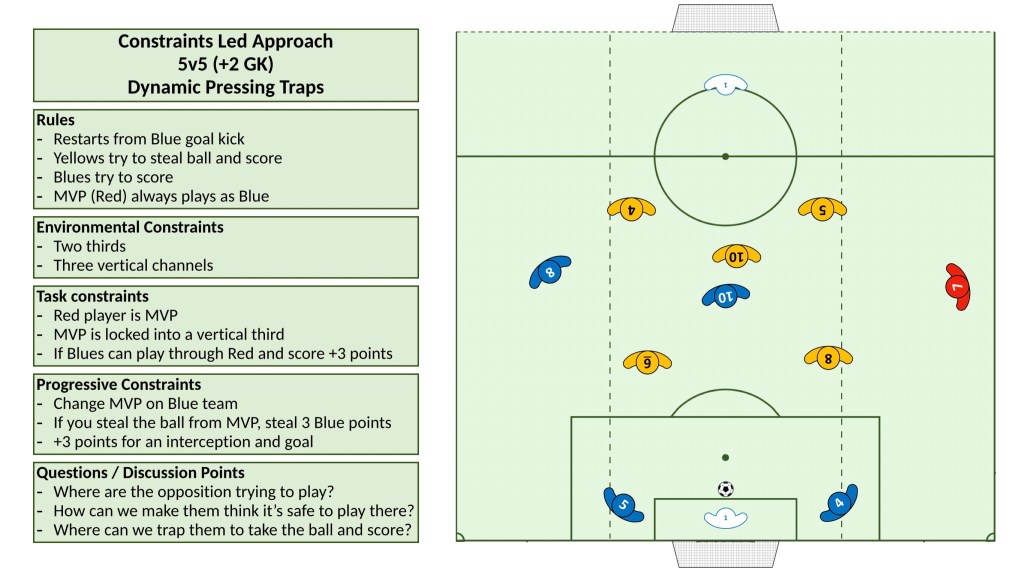

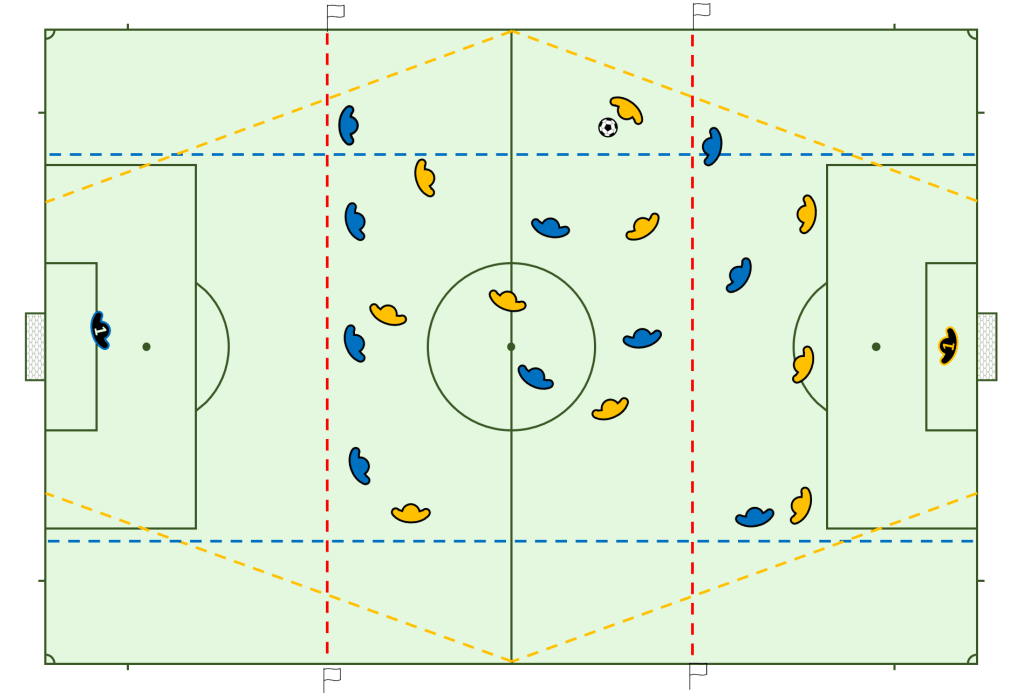

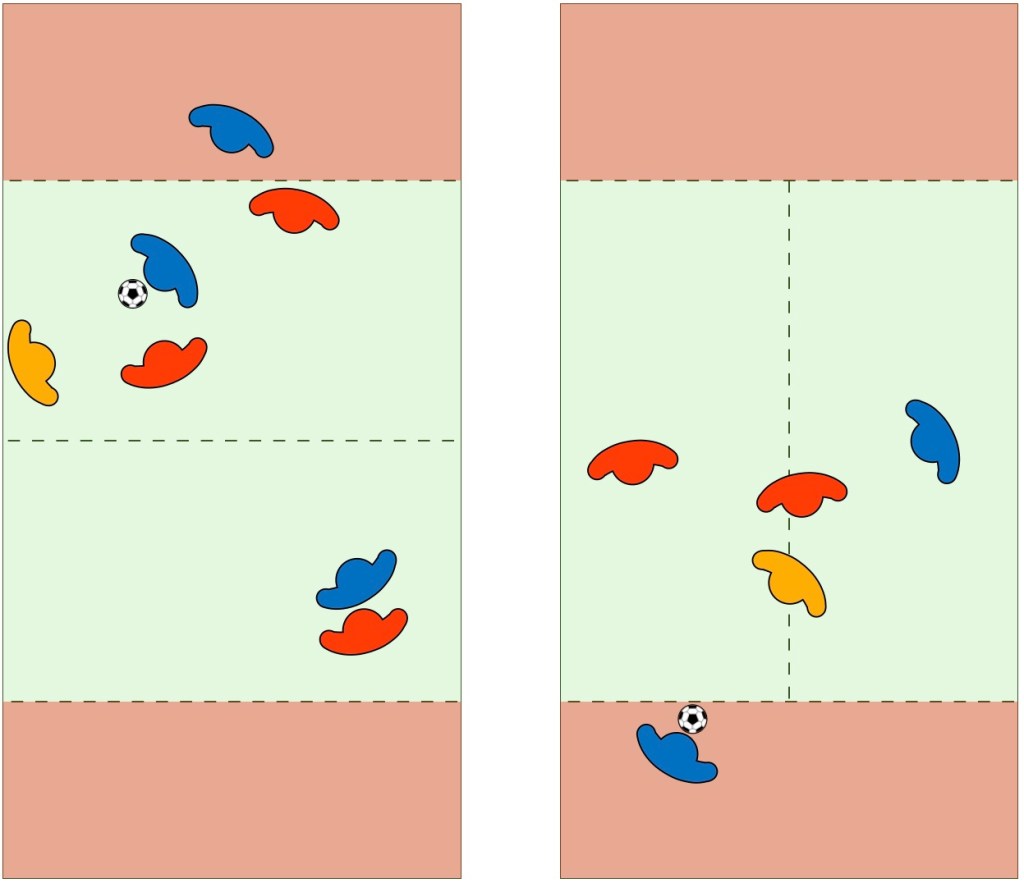

The image below shows a practice designed [by Aslan Odev] to draw attention to the opposition’s back line. By constantly changing which backline the players are using, they have to constantly readjust dynamically within the game, and find solutions to the ever changing problem. Within the practice, you will see players building, creating and finishing. Similar to the game, they are one and the same.

The Way Forward

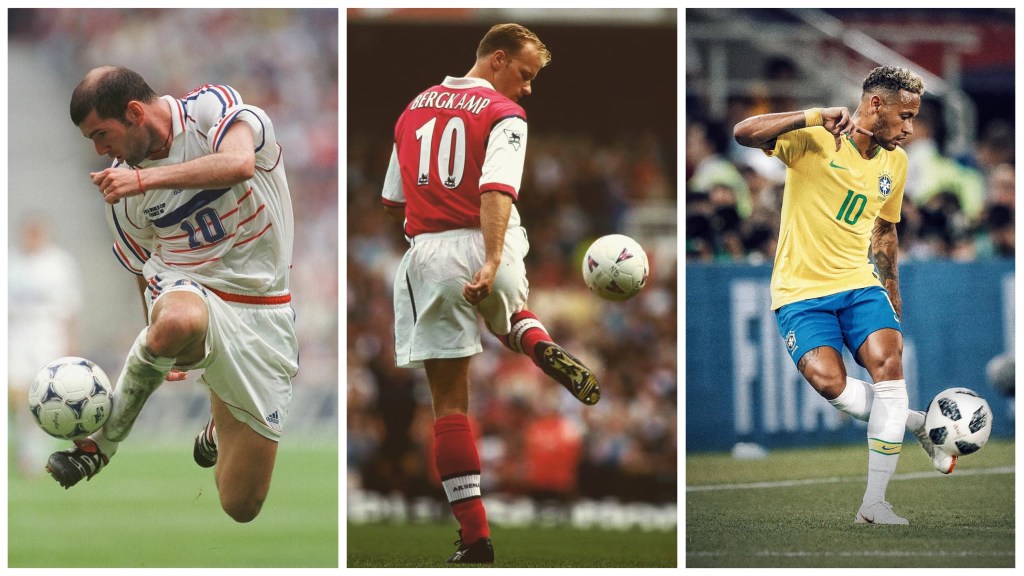

Football isn’t a series of boxes to check—it’s a dynamic, unpredictable game that demands adaptable players and coaches. The best footballers in the world thrive because they bring something unique to the game, not because they conform to a predefined mold.

It’s time to abandon rigid structures and embrace the messy, creative, and individual nature of football. Only then can we truly unlock the potential of our players.

Amongst the Chaos

Control

Is our addiction to control destroying our most creative players? It seems we may have strayed further than a simple need for control of the ball; we want to decide every single moment, every movement, every position, every thought.

We want to control the player and their every move. Only, controlling each player’s actions comes at a price. We lose their perception of the game and, therefore, their identity and creativity in the process.

But where does our cry for control come from? We’re going to explore if positional play is the answer to developing creative and unique footballers, what the alternatives are and how to train players to think for themselves and find unique solutions on the football pitch.

Positional Play

So let’s start here, what’s wrong with positional play (PP)?

Positional play decides what the players do and when they do it. You may hear that through PP we give the players freedom within the rules we enforce, however, this is no freedom at all, for we have predetermined the answers from which the players can choose. This is not freedom, but an illusion of such.

Essentially, positional play attempts to maximise efficiency by limiting the player. The player must stand and occupy spaces on the pitch to affect the opposition’s defensive system, and then after receiving the ball, the players have a set of options from which to choose.

And through the rule of occupying predetermined spaces, we remove freedom of movement and therefore the freedom to create spaces through creative, spontaneous play.

So, when it comes to development, what exactly is the problem? Well, a PP system is ultimately decided by the coach. The system comes before the individual. However, if we are so determined to develop unique individuals, individual development can’t come second.

Being part of such a rigid system has many drawbacks, especially within the paradigm of development. There is no freedom of expression for the player, no original thought. The players become robots, they lose themselves. We stop our players from developing a unique identity. They lose what makes them special. We make them like everyone else.

And what’s worse is, this style of football, which hinders a young player’s development, is rife within the academy system and is spreading to grassroots. We have to ask ourselves a fundamental question, when it comes to development, what do we want to see?

A system which shows off some of our knowledge as coaches and will limit our players?

Or, a system built around the individuals within the group, allowing them to make decisions on how to build, how to create and how to score. A style of play which will likely empower and encourage new and unique ideas.

I know which one I’m after. And through modern interpretations of practice, if we break free from the norm, there is another way.

Pawns

The honest truth, though we may not want to hear it is this; positional play is a style of play to show the ego of the coach. The coach picks when and where their team attacks, which actions the players can take and ultimately limits the player’s decisions. It’s to show the knowledge of the coach, not the knowledge of the players.

One of the many problems with this approach is these predetermined attacks are scripted and once another team has seen the script, it becomes easy to stop. And if this rigid plan is stopped, then the players look around not knowing what to do until the break when the coach can take over again and offer them a new solution.

This is not how we are going to develop creative, intelligent footballers and if this has been a player’s whole football education, they have no way to adapt, to find a new answer, to find a way to succeed. The honest truth is, we set them up to fail.

It’s becoming increasingly more frequent to hear the comparison between football and the game of chess. In chess, there is a chess player, who dictates the movement of the pieces. The pieces have fixed movements, and when can these pieces move? When the master decides.

But there’s a fundamental problem here, footballers are not chess pieces who can’t think for themselves and they do not need a chess master to govern their movements. In chess we give life to static objects by giving them purpose – rules in which they can move. In football, we’ve limited human expression into lifeless objects who are bound by the limits we enforce.

We limit our players into behaving one way, that suits the system and through this we lose individual character and creativity. This stems from two things, Pep Guardiola being extremely successful with his positional brand of elite football and our very own fears and insecurities.

We want control, our image on the pitch, our vision, we want to show what we know – but in this quest to show our own knowledge we’ve lost what is most important, the development and the knowledge of the player. This is, of course, the very essence of a development coach.

Freedom

We must remember that when controlling possession, building from the back and playing through the thirds there is not only one way to attack. Just as high pressing is not the only way to defend. These styles of play are not necessary to win games of football, nor are they necessary for the development of world class footballers.

You could argue that moving the ball more, having more possession will allow for more interactions and therefore more technical and skill based development.

I too believe more interactions are beneficial, however, this doesn’t mean we should enforce one version of possession football onto our players. Some of us might like shorter passes, players closer together for more interactions, however, in development, we don’t want to undervalue the long pass, we don’t want to undervalue stretching the opposition.

We must be open to all opportunities to attack and defend, and our job is to highlight these opportunities to our players, not instruct them. And it is for our players to take this information and act upon it however they see fit.

Only then will real development take place. This is the safe space we must create, where the players can try things we wouldn’t, and work things out for themselves. I can honestly count on one hand the amount of coaches at the top level that actually do this.

The Constraints Led Approach (CLA) constrains, manipulates and stretches the boundaries of practice to highlight problems the players may face in the performance environment (game day).

However we must be careful not to over constrain, or only highlight one aspect of the game. I have been working within the world of the CLA for almost a decade now, and something I have come to realise is that change and variation within practice is where the real learning happens.

Schöllhorn

Differential Learning

As my understanding of development and learning evolves, I am increasingly intrigued by Differential Learning. Differential learning is a motor learning method that was proposed in 1999 by Dr. Wolfgang Schöllhorn, and works around the premise that the learning of an action or movement is dependant on the amount of noise created (practice variability).

As discussed in a previous article written for theRaumdeuter, ‘We need to talk about technique…’, our aim as coaches should not be to reach for ‘the one perfect technique’, but instead for skilful adaptability. In other words, rather than perfection of particular techniques, we should aim for a wide range of variability of techniques – the idea is that this approach will lead to players being so adaptable, that they can overcome any problem put in front of them.

CLA & DL

Whilst I promote the use of the CLA and DL, it is important to understand that there are differences between the two and how we use them will determine how our players develop. Here are the main differences that have made an impact on my understanding:

DL

In DL, the idea is to create enough stochastic resonance (aka. noise/variation) as to not engage the frontal lobe of the brain.

The problem with engaging the frontal lobe, is that this is the part of the brain that plays a role in judgment, empathy and reward seeking behaviour and motivation.

Judgement, in football development terms, will lead to behaviour that will lead the athlete behaving in ways that will interrupt the learning process. For example, if an athlete attempts to dribble, and falls over losing the ball, they will feel judgement from their peers to maybe not try again.

Many of the brain’s dopamine-sensitive neurons are in the frontal lobe, dopamine is a brain chemical that helps support feelings of reward and motivation. So if the coach says something like, ‘Mujeeb, well done for switching the ball out of trouble there.’ This will engage the frontal lobe, the player will feel a positive hit from the dopamine, and begin to behave seeking more of the same reward.

Now Mujeeb will begin to behave as if tight areas are perceived as ‘trouble’ and big spaces afford the most opportunity. (What we will look at later is how there is opportunity in every situation on a football pitch) So if we praise a player blindly, it can lead to poor decision making in search for dopamine.

With empathy, maybe a player shoots and misses the target, there is a free player in the box who feels the ball should have been played across to score. The player will feel empathy for the missed opportunity and this will shape how they approach similar problems in the future.

We want to avoid engaging the frontal lobe in practice so the player will stay in a continuous process driven state. We do this through constant variation of the task, environment and individual boundaries. The athlete is to learn without correction or feedback. This is essentially Differential Learning.

Think of a baby attempting to walk, when they fall over, the frontal lobe has not reached the stage of feeling judged, so they just get back up and try again. They are in a constant state of process, a constant state of learning from within their own experience. This is the state that DL attempts to reach.

CLA

The CLA works on the premise that you can manipulate the task, environment and individual constraints to highlight a particular part of the game. The practice will offer affordances (opportunities to act) in line with the constraints you set, however the difference is these constraints are not changed as often. It is common to see a CLA practice’s constraints remain until the athletes find success.

These constraints, if left without constant change, will engage the frontal lobe, giving the players time to feel empathy, judgment and reward seeking behaviour.

Isolated Practice

The CLA requires representative design, the idea that for a representative practice, you need a ball, direction, an opponent and consequence. Where this breaks down is that there is no space for isolated practice. When looking through the lens of the CLA, isolated practice is not representative, and leads us to believe that there is no skill acquisition available within isolated practice. The problem is, we cannot say for sure that isolated practice does not contribute to an athlete’s skill acquisition at all.

Where DL differs, is that the method does not require opponents to support the athlete in learning. All it suggests, is that you need constant variation to not engage the frontal lobe.

Take an unopposed passing practice for instance, the practice itself offers little in the way of motor learning. However, through the lens of differential learning, it does offer something. There is often little to no variation within an unopposed passing practice, but, why do some coaches swear that it develops certain skills in players?

Because it actually does. But not for the reasons that coaches are often led to believe. One thing that the CLA and DL have in common is that repetition to reach a perfected technique does not improve a player’s skill level. Actually, through the ages of growth is where we see most improvement with drills like this, not because of the practice, but through the variation caused by growth.

In fact, doing almost anything with a ball whilst going through periods of growth will cause enough stochastic resonance to help the player learn. Whichever of these lenses we look through, this type of practice really is the absolute bare minimum when working with our players, I would absolutely advocate for using these as little as possible when compared with CLA or DL practice design.

Finally, there is noise in the CLA, there is variation, enough for players to develop much more than traditional coaching methods. However, if we want to develop the best and brightest footballers in the world, I think we can and should go further.

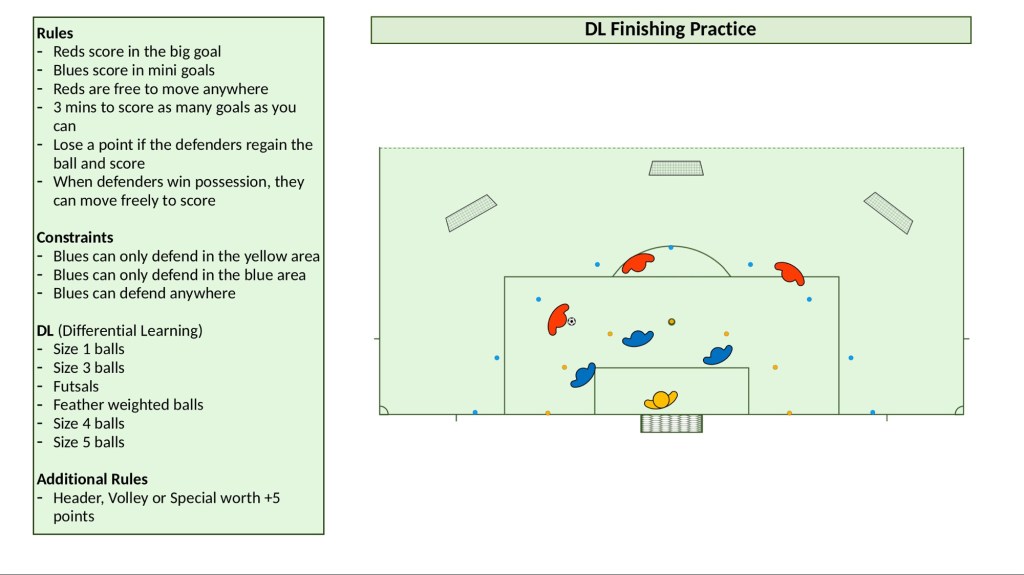

DL Finishing Practice

So what does a team based DL practice look like? Let’s look at finishing. Traditionally, finishing practices contain very little variation. Below is a finishing practice designed to add tonnes of stochastic resonance/noise/variation. You can adapt the rules of the practice as you see fit for your players. You adapt this practice easily to incorporate more or less players.

You can even do this with one attacker and no defenders, although there’ll be less stochastic resonance than what we would ideally search for, the variation from the different types of balls will support your athlete’s finishing development.

The idea is that the defenders are locked into zones to block, they can tackle if the ball enters the zone they are currently occupying. Again, the idea is to not engage the frontal lobe. So change the area size frequently.

What you are likely to find is players adapting in real time to the different environmental challenges from the balls and the opposition’s constraints.

I have been guilty myself of only highlighting one problem through the CLA, asking the players to repeat the search for a solution to one particular problem. And through this misunderstanding of practice design, I found that this isn’t enough to develop players to reach their highest potential.

For example, what happens when that problem inevitably changes on game day? We’ve practiced playing against a back four, now they’ve changed to a back three. The players become lost, and we have to step in to ‘guide’ them through a problem they’re not equipped to solve.

So, this begs the question, how do we develop individuals who can dynamically seek out deficiencies in the opposition? Who can identify where the gaps are appearing and how to create their own gaps to exploit. And how do we train this? Rather than the players following a rigorous set of rules, can we develop them to think for themselves?

Thankfully, yes we can. Below is a carefully constructed practice which helps develop player’s awareness and creativity. (Whilst viewing these practices, it’s important to understand that we are not looking through the lens of positional play, players do not have set positions they must occupy, but rather their positions are to be taken off of the position of the ball and the opponents.)

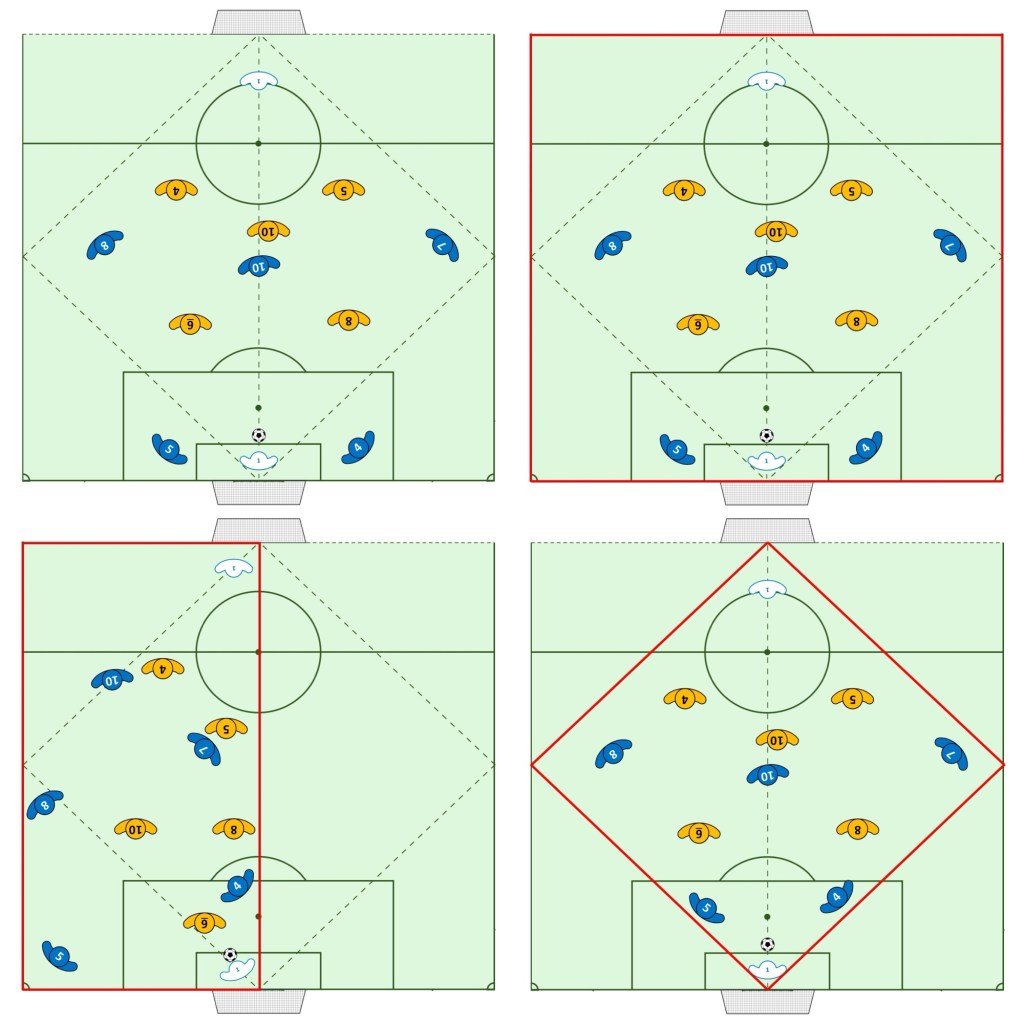

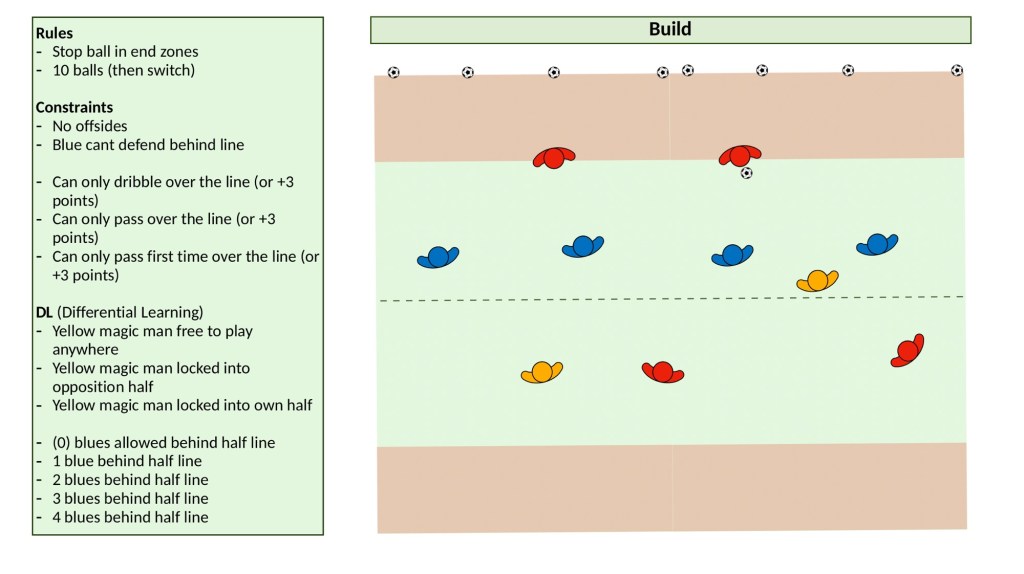

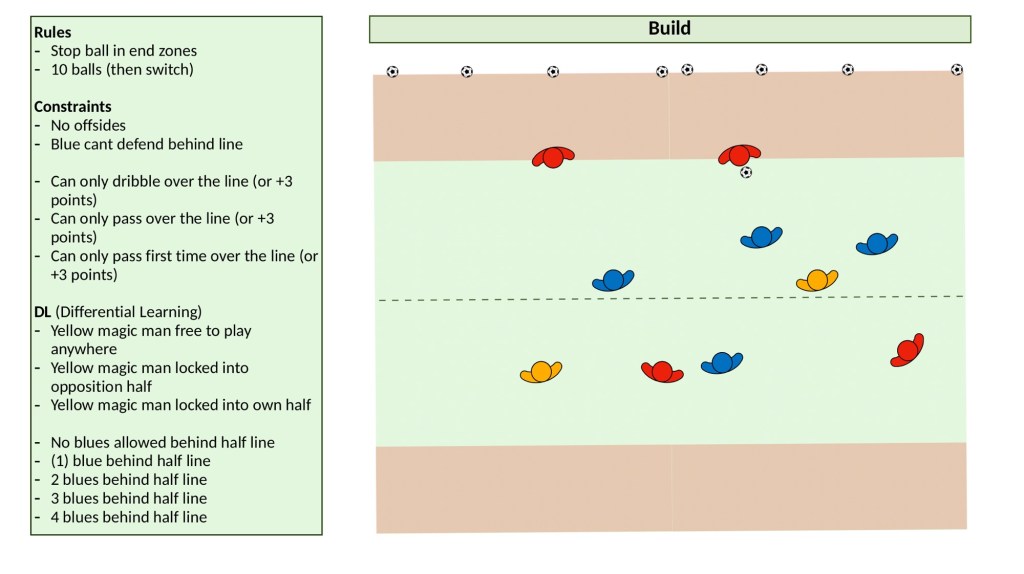

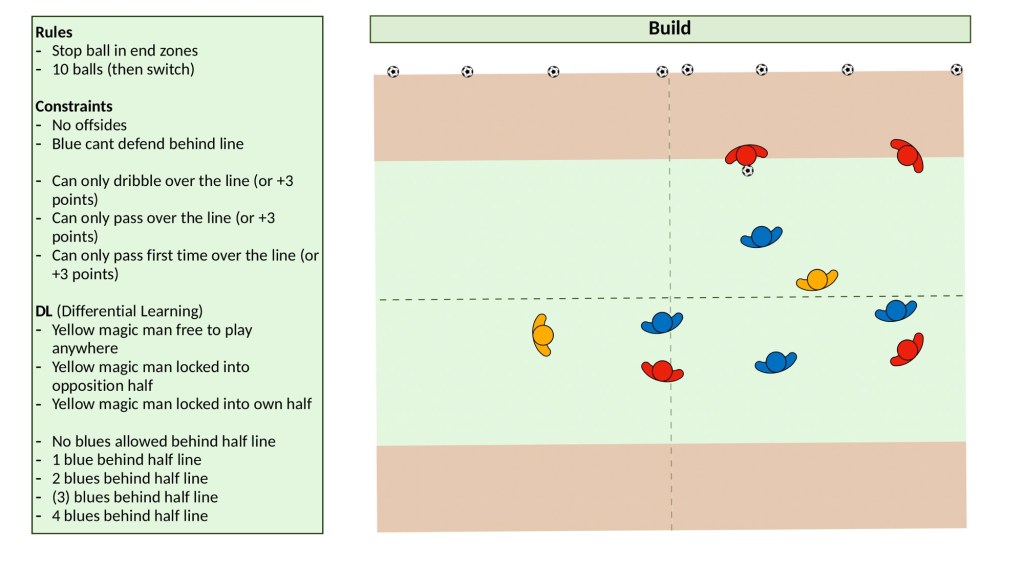

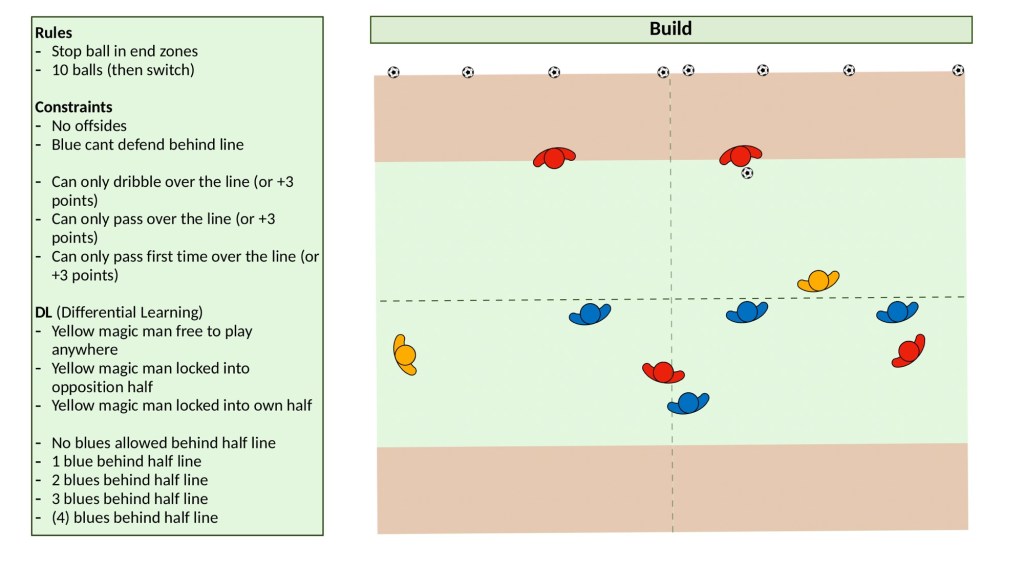

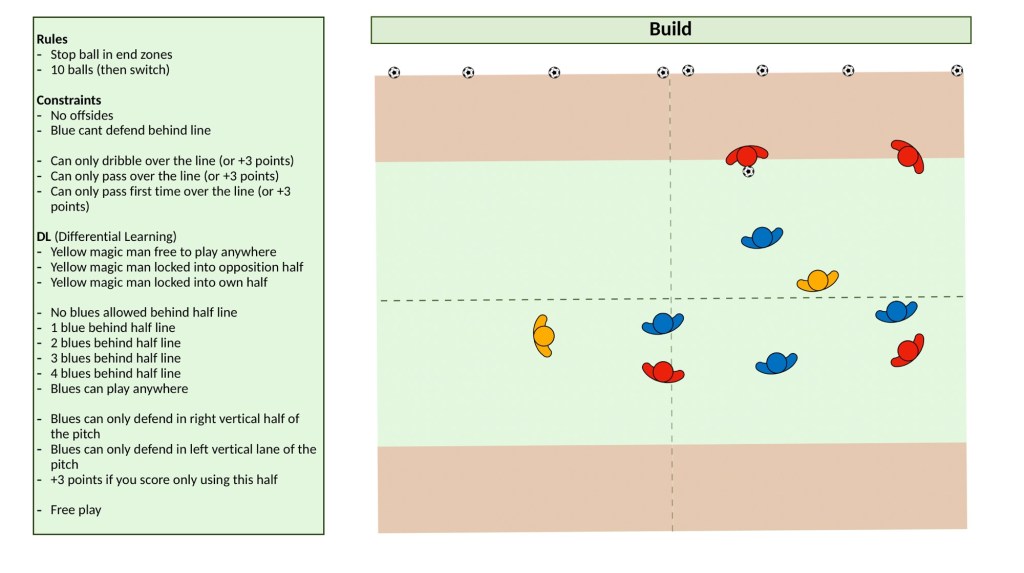

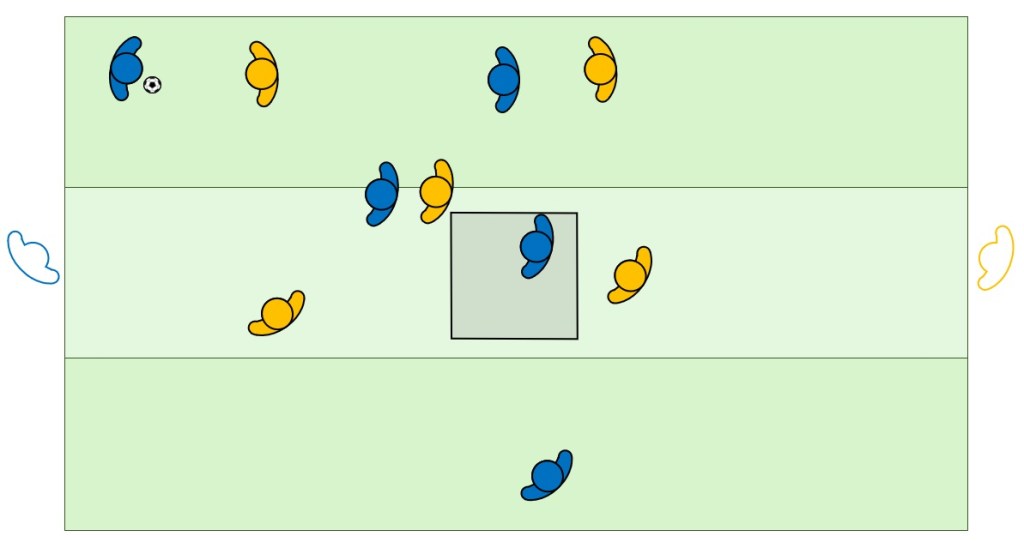

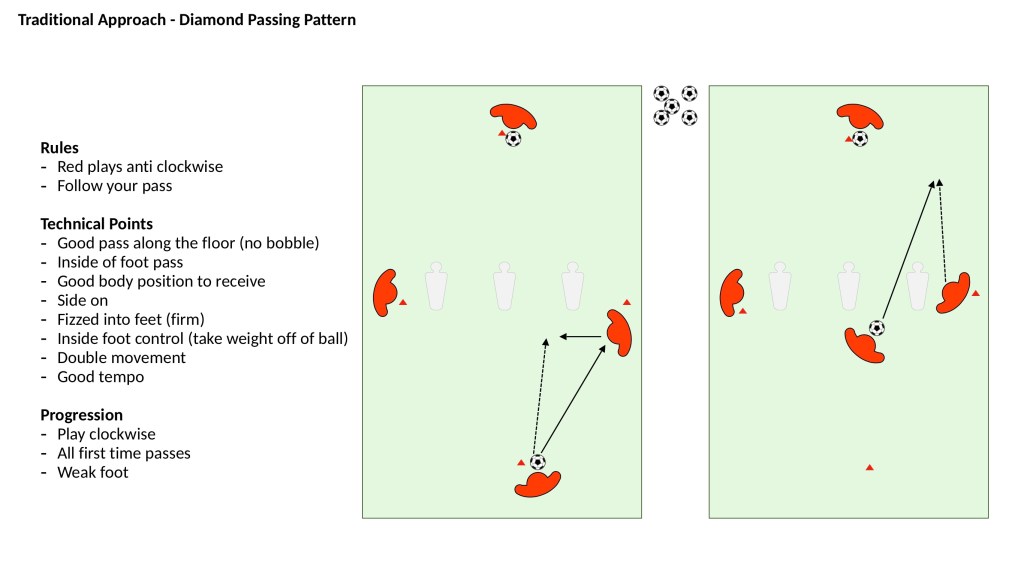

Build and Break

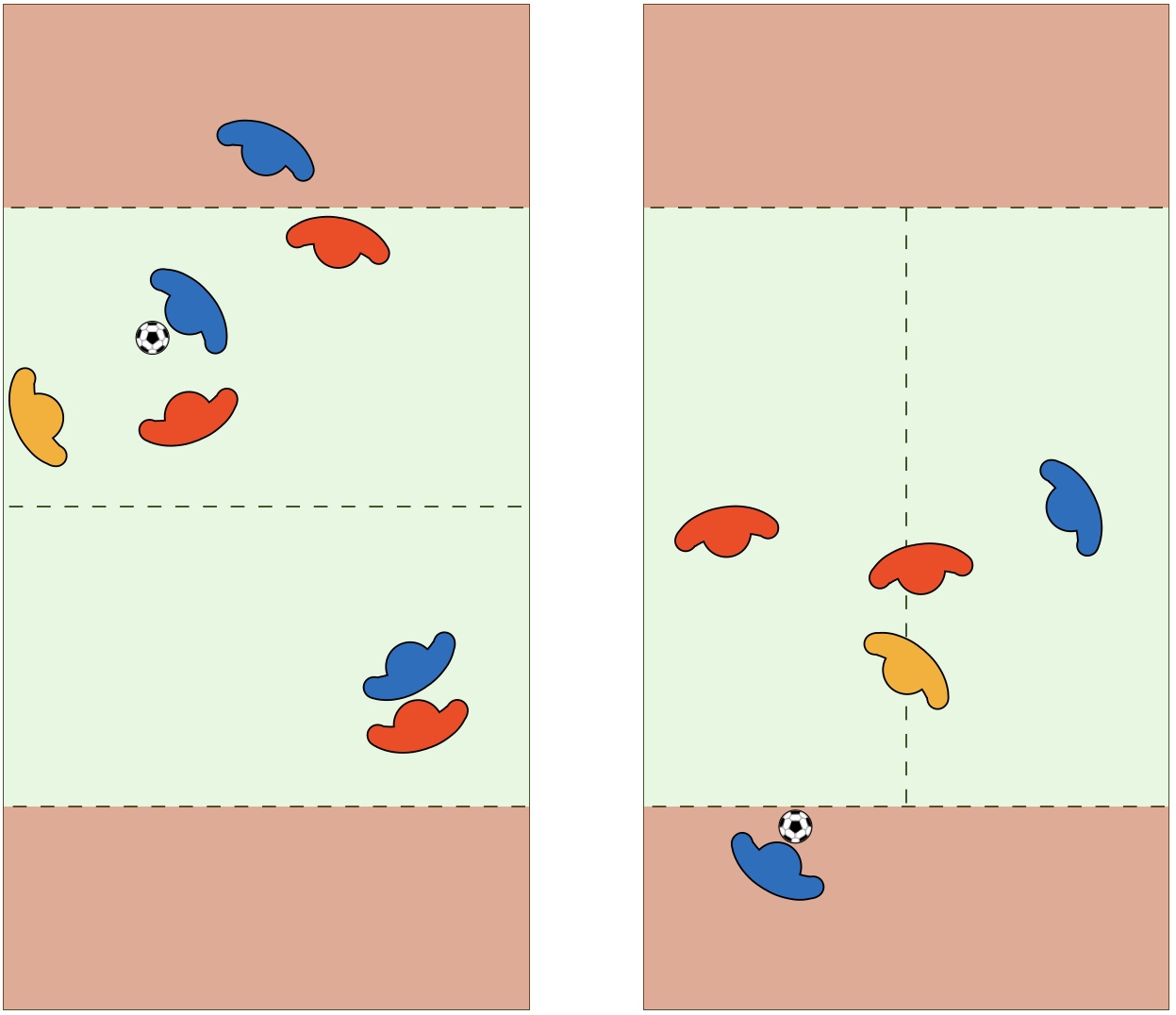

Below we will show a ‘build and break’ practice, designed to help players break apart basic defensive structures, in order to progress into more attacking spaces. This practice can be tailored to all age groups and any number of players. The rules are simple, get the ball from one end zone to the other.

The difference? Below pictures of the same practice with different constraints/boundaries being applied. The first constraint is that the blues can’t defend behind the halfway line. This will make them defend in a certain way, forcing the attacking team to act.

This is a keystone in constraints based coaching, constraining to afford. Essentially constraining the defenders so they act in a specific way, and therefore your attackers will act against that. As you scroll through the practice designs, new rules are applied; now one defender must defend behind the halfway line, then two, then three and so on.

Rather than just playing vs a defensive four, or a defensive two, the idea is to constantly change the opposition so the attackers have to self organise and work out solutions to new problems in real time, in game. These boundaries are to be changed every minute or so, this gives the attackers no time to relax and they stay in a constant state of problem solving, or as Wolfgang puts it ‘stochastic resonance’. This is what we are searching for, this is the developmental sweet spot.

Now, when it comes to game day, the players should be able to see and act upon whatever is in front of them. The idea is to ask them to constantly solve ever changing problems without the need for anyone to decide how to overcome these problems for them. Our job as the coach? Become obsolete.

There are also additional rules above, such as ‘Blues can only defend in the right side of the pitch.’ Again, this will change how they defend and this will then change the behaviours of the attacking team. These rules are ideas to constantly change the environment.

All of these rules are to be added gradually, and changed often. Allow some free play as part of the block as well.

We may feel it necessary to allow short breaks for the players to discuss how they’ll overcome these problems. One nice idea is to give each team a ‘time out’ they can use in each block at any time. If we give them more than one time out, I think it’s important to make these shorter each time so they have to be very deliberate with their communication.

Now all that’s left is to sit back and observe how our players attempt to overcome these problems, be careful not to go in and ‘fix’. Observation is key. We must get to know our players and how they approach the problems set. I’m often surprised with what some of them come up within this chaotic form of practice.

Opportunities to Act

It’s important to recognise that most of the hard work as a coach is done in the practice design. There is no need to constantly move in and force our opinion of how the game should be played when developing our players.

If we create a rich environment, full of opportunities to act, our players will choose how to solve these problems without much need for us to step in, we are simply there to bring their attention to these opportunities.

Observing is the best thing we can do, then asking our players to consolidate their learning; ‘Teddy, I’m interested as to why you chose to do that in that situation, could you explain why you made that decision?’

In highlighting their attention to things you can see that they may have missed. ‘Sarah, I noticed something when you had the ball just now, did you see Toby in a lot of space on the right hand side? You don’t have to give him the ball, but just be aware that he keeps taking up some good positions.’ Sarah may decide to use Toby, she may decide to fake using him, or ignore him all together – ultimately, it’s up to her.

What we are trying to avoid here, is everyone using Toby in the same way. How every single player approaches each problem will be different and that is exactly what we’re after. Individual thought.

Now we’re a part of their learning. We’re helping them see, highlighting opportunities to act, but not telling them they must act in a certain way. We are collaborating with them. All that’s left to do is sit back and watch the cogs turn as they become more ‘attuned’ to their environment.

And remember, there are no RIGHT answers. To be able to coach this freely, without the shackles of right and wrong, we might need to bust some unspoken footballing myths.

Myths

To break free from the constraints of control, first we must destroy the unspoken myths of modern day football…

Switching Play: Switching play is a regular theme of practice within academy football. The internet is riddled with ‘switching play’ practices, all with the same basic message. ‘Get the ball away from the chaos.’ But, what if by moving the ball away from the opposition, we are also moving the ball away from opportunities to play and create?

There is no need to switch the ball out of tight situations. There, I said it. When players are free on the wing, we think that we need to switch the play away from the rest of the team and put our winger or fullback in a 1 on 1 situation alone on the other side of the pitch, regardless of if they are a 1v1 player or not.

We’ve all heard shouts such as ‘switch it!’ from a coach on the sideline, then a player ignoring that instruction, faking playing wide and creating a new opportunity to play forward in amongst the chaos. The coach then claps and tells them well done, despite two seconds ago demanding that the only possible answer was to play the ball ‘out of trouble.’

There is absolutely no need to switch the ball out of a tight situation, it is one of many options, but not the only option. Some players may be able to play through that tight area with clever fakes, dribbles, passes and touches. We must allow our players to explore all the options, not just one. Within chaos, there is also opportunity.

Maximum width: Maximum width is not necessary to create space in a game of football. There is a place for stretching the opposition – pinning back the fullbacks, and keeping the width in order to create gaps in the opposition to play through.

It seems logical, and as PP systems have evolved, they have had to incorporate a strong rest defence to cope with the loss of possession into spaces created by having our players so far apart and far away from the ball, this has birthed the rise of the inverted fullback. However, none of this is strictly necessary to be able to play controlling and attacking football.

Every coaching course you attend points to maximum width as an integral principle of the game. When nearly every coach steps in on match day, you will undoubtably hear the phrase ‘where’s our width?’ Or ‘make sure we’re high and wide!’

However, when you begin to look closely, this often hinders the players more than it helps them. I’ve often seen these rules demanded from players, and they stand there, lifeless, just waiting. They’re not involved in the game, and unfortunately, following strict instructions will not help them reach their full potential.

Just like with switching play, there is no need for having one player hug the touch line. Maybe if you have a player who likes to isolate 1v1, but as a general rule? Remember there are no rules, players have to be free to find what works for them. The players must be able to explore options other than one style of play.

How often, for example, have you seen a player attempting to move into a central space to receive a forward pass, and is immediately told they must create width for the team. Now the player has lost their curiosity for dynamic spaces. They now just stand where they’re told. And just with that one phrase, their curiosity is gone and so is their potential. What if they found a new space inside the pitch, got on the ball and created a scoring opportunity for their team? We’ll never know.

Relativity

So what’s the alternative? Well it doesn’t have to be so black and white. If you want to create gaps in the opposition, do you NEED maximum width of the pitch? Can you not create enough width around the opposition? What about minimum width? What would happen if we changed our coaching philosophy to incorporate relative width? Taking position off of the ball and the opposition?

We have come to accept that maximum width is a set principle in football. It is not. There are no rules. When the development of the player comes to the forefront, I say that the players should decide. And when we speak about the development of young footballers, they are being hampered by this over simplification of the game. Maximum width should be a choice of the player for a reason. If they can not make that choice and we make it for them, we are cheating them away from their full potential.

Let’s start a new principle: ‘Play where the ball needs you to be’.

Creativity is only needed in the final third: ‘Wait for the ball in these spaces and we’ll move the ball to you’: Another positional play principle. Stand here and we’ll get you the ball. Think about all the interactions you instantly kill by forcing players to do this. I’ve seen it with my own eyes, players wanting to drop out of midfield to pull an opposition midfielder out, creating gaps to play through. Instead, no, stand in there and wait.

We talk about creative players as if they only ever belonged in the final third, every player on the pitch should have the responsibility to create. Why can’t a centre back be the most creative player on the pitch?

We forget that creative players can exist all over the pitch. Players that were ball orientated. We kill them before they’re even born. ‘Stand here and wait for the ball’, is by far the worst phrase in football development. We tell the players how they should build, how they should create, how they should attack. What about the players that can create the opportunity, not to score or assist, but what about the players who can create the opportunities to build?

Break Free from the Shackles

When we set up a practice, it’s important to think about whether we are allowing the players to explore all of the options the game has to offer or whether we’re just imposing one way to play onto them.

When we hear someone say, ‘you must be high and wide!’, or ‘where’s our width?!’ Ask them ‘why?’ What about the opposite option to that, what about everything in between?

We must stop accepting these make believe rules as truth and begin asking your players to explore the game. Maybe they’ll come up with something we have never seen before. Something new, something organic.

Turn up the Noise

More noise, less structure. You want your players to build out against a front three? Ask them build out against a front 3, 2, 1 and 4. Watch, as every few minutes you change the opposition shape, they begin to solve new problems together. Watch the team work together and the new ideas unfold.

They’ve solved playing out against all of these different formations? Change the pitch size: Narrow, Long, Short, Wide, No Corners, No middle.

Change the task, often: Build without going around the opposition +3 points, build without going through the oppostion +3 points, Build without playing over the oppostion +3, free play.

Change these boundaries/constraints and change them often. Watch the players work hard to overcome, to learn what works for them. Watch as they create opportunities to win the practice.

It’s too quiet, turn up the noise and find the joy of true footballing expression amongst the chaos.

Part 2: Straight from the training ground

What needs to be in practice design for transfer of learning

Building upon the insights shared in part 1, where we delved into the nuances of transfer (near and far) and design practices that optimise player learning for peak performance in competitions. In addition, we included theory to support our writing and practical examples to analyse where they might sit along the ‘Near and far transfer spectrum.’

This sequel extends our exploration, shifting the focus to the practical realm of representative practice design. We’ll outline the four key components that contribute to crafting representative practices, fostering near transfer for players and developing adaptable skilful players. Anchored by ecological pedagogy, this methodology enriches our football practice planning with purpose and direction, always guiding our ‘how’ in the quest for effective player development.

Good ingredients without a set recipe

Imagine the game of football and all of its elements are a whole cake. Passing, dribbling, opposition, transition, size of pitch and everything else are the layers, toppings and fillings of the entire cake. When you go to have a slice of the cake you want to try the whole thing not just certain bits. This is what we are aiming for in ecological pedagogy. When we take a part of the game (a slice of cake), we want all of the key elements of the match (the whole cake) to be represented in our practice design. Then we can utilise constraints, challenges and/or objectives to highlight moments or focus on situations/scenarios of the game where the players will explore solutions both individually and as a group. The role of the coach is to prompt the players to think about what they saw before/during/after the action (attention), what they tried to do and why (intention) and then observing the learning process as the player adapts both of these after open questioning and guidance from the coach, their team mates and/or themselves.

Education of attention– a change to using and seeing a more useful, specifying source of information to control your movement

Education of intention– a change in the aspect of movement you are controlling

Calibration– change in the relationship between the two (attention and intention)

Being skilful is not a process of repeating a solution, it is repeating the process of finding a solution

Richard Shuttleworth @skillacq

Only using decomposed and traditional practices are like just taking the icing of the cake. For example, practicing one focused element of the game while losing all the other relevant parts that influences the player’s decision making. In a previous article, I explore how mannequins are not ideal when learning combination play while highlighting the variables that will influence a player’s attention, intention and action including teammates. opposition, ball and space.

Utilise the constraints led approach and other ecological pedagogy and design practice to focus on one part of the game while leaving as many of the key elements of a match present.

What is needed in training?

Four components for a transferable practice

- Representative information

- Action fidelity

- Affordance landscape

- Emotional context

Representative information

So what is representative information? In football there is information on the pitch that will influence a player’s decision like where team mates are, where the ball is, where the opposition is and where space is. Players perceive the environment by picking up information to guide action (in accordance with their own action capabilities). In training, this information should be present in a relevant and similar way for there to be near transfer to match day. The players need to experience realistic force, direction and timing for an effective learning process.

The players need to feel and explore a representative environment to build knowledge in the game with contextual force, timing and and direction and that can only happen with representative information present in training.

Force can come from the opposition pressing to regain possession or the speed and trajectory of a pass from a team mate. The timing will be present through the movement of team mates and opposition as well as when a pass is played or the type of touch a player takes. Finally, the direction will be represented by the goals or end zone players for team mates and opposition to orientate themselves in defensive and attacking phases of the practice. In addition to this, specifying practice is important when taking a slice of the cake. Understanding a phase or moment of a match and trying to replicate those key elements in training will increase the learning for the players.

Action fidelity

In this context, action means movement, and fidelity means the accuracy that something is copied. So action fidelity in transfer of training refers to the degree that action executed by the body in practice is similar to competition. Movement solutions encompass anything the body can do, in football this would include the technique a player chooses to perform a skill, the co-ordination of running or changing direction, jumping to win a header and everything else.

So how can this influence our session design? Relevant force, timing and direction in the practice are key elements for near transfer and we can create these from the task, opposition, team mates, area size and equipment present in the practice. For example, the size of the practice area will change the affordances (opportunities for action) the players can explore. A bigger area will allow for quicker and longer running speeds as well as positioning and managing risk to a higher level. Whereas a smaller area will give different affordances, quicker decision making, more of a focus on body shape when receiving, timing and force of pass, first touch direction will be heightened and jeopardy increases.

Affordance landscape

Affordance is the opportunity for action and the landscape is the environment the player is in (the pitch) including team mates, ball and opposition which will determine the space.

The environment needs to be dynamic and unpredictable, it is imperative the players experience the process of finding a solution and not given a predetermined answer. The environment should also be continuously adapting as the player interacts, i.e. the player not shooting first time and then having to adapt and look for a different opportunity for action. Affordances are appearing and disappearing because of how the athlete interacts with the current environment (controllable) and the changing environment – team mates, opposition (uncontrollable). Also, each athlete’s affordances are different and the practice should allow for independent differentiation. For example, a player who can dribble well will perceive different opportunity for action that someone who is a great passer of the ball. Choice and the opportunity for these actions need to be available for the players to explore and then the role of the coach is guide attention to a range of affordances to shape the player’s intentions.

Practice design along with relevant constraints and challenges will provide an environment rich in opportunity for exploration. Remember we are trying to take a slice of the cake with all the layers, icing and toppings! There are ways we can scale back or increase the complexity and difficulty of the information through underload and overload design (adding or removing noise), i.e. 4v4 into a 4v2 for an in possession practice to give the players less noise, while keeping the relevant and influential elements of match day for near transfer.

Emotional context

We are trying to create similar (not exact) pressure and risk to evoke contextual emotion to match day. In competition, there is real failure and each decision has different value depending on the game state, the decision taken on match day will be better if the process of learning in training involves similar pressure and risk. We cannot replicate the pressures of a crowd or parents in training but through a variety of pressures the players will learn to be resilient and adaptable. This is what we are aiming for, players who can still be creative in a high pressured environment when the stakes are at their most important and the consequences of their actions mean far more.

Pressure, risk and jeopardy can be created and emerge in a plethora of ways and does not have to be exactly the same as the criterion task. We know players are inherently competitive and they feel failure if they misplace a pass regardless of the environmental pressures, our roles as coaches is to increase the noise (difficulty) in training so players are adaptable and resilient. Including extrinsic motivation like a trophy or a captaincy on the weekend is a great and fun way to increase desire to win in training but will also increase the value of each action and decision, keeping score is a strategy that is relevant and easy to implement especially within 1v1 or 2v2 scenarios and duels, setting quantitative targets to individuals for elements of intrinsic motivation.

Ultimately, we want risk and pressure present in practice design so players experience emotions relevant to competition in their learning process. We want resilient and adaptable players who can find success in every environment and context.

You can have your cake and eat it

Below are two practice designs that will look at how we can utilise the CLA in an 11 v 11 session and then in a smaller 5 v 5 + 2 game. Practice principles should be considered for both practices and should only be used as guides for coaches to adapt depending on where the players are in their learning process. The implementation of individual challenges and the adaptation of constraints is the art of coaching, understanding the needs of the players and what will stretch them appropriately is so valuable. The readiness to change, add or remove challenges is the skill of a good coach and being observant to how the players are interacting with their environment will provide the information required. Evaluating the practice design to ensure near transfer we need emotional context

Practice principles

Focus on being compact and setting traps out of possession

Organisation

- Blue team vs Yellow team

- Team out of possession- to defend their end zone player (Yellow defends yellow end zone player)

- Team in possession- to try and play into opposite end zone player (Blue passes into yellow end zone player)

- Game continues when end zone player receives the ball but plays into own team

- Restart points- goal kick, throw in (deep and high), centre spot and rolling ball from coach

- Use of score for competition, set a scenario e.g. 1-0 down with 10 minutes left in the World Cup final, winning team get a prize etc

- Individual strategies-

- ‘Captain of defence’ – player to take responsibility of organising the defensive structure (more than 1 player and can be in different units)

- Try to intercept rather than tackle- highlight and focus on approach and setting a trap

- Duels- pair players from opposite team and ask them to keep score of times possession is regained by a tackle or interception

Recommended constraints/challenges

- (IP) Try to play through the middle area and pass to opposite end zone = 3 points otherwise = 1 point

- (IP) Try not to play back into own end zone player / Can only use own end zone player once in same phase

- (OOP) Try to defend across 2 vertical lanes / Can only defend across 2 lanes

- (OOP) Try to regain possession in a certain lane or middle area (set a trap) and play to opposite end zone player= 3 points

- (OOP) Addition of horizontal thirds as well as vertical thirds for defending team to play higher

The whole cake with a twist

With an 11 v 11 game the representation to match day is close and the key elements are present but within this we can utilise the constraints led approach to highlight problems for the players to solve. In the practice below the focus is on how the out of possession team can remain compact while setting traps to regain possession, the constraints in place ‘OOP team to try and defend across 2 lanes’ will guide the group to being compact and shuffle across to deny space, this will encourage a good first press nearest the ball to prevent the switch, the in possession team are given the incentive of trying to play through the middle area for extra points. Both of these will guide attention for individual and group also neither are mandatory, this empowers the players to explore and retains the realism of choice on match day.

A slice of the cake

Smaller sided games will give the individuals more opportunities to find solutions but will obviously miss some elements of representation we would see on match day. No goal, no goal keeper, less players but the key elements are present for the learning process. The timing, force and direction to what they would face in competition are present therefore the affordances the players experience are close to match day.

Below are some questions you can take with you and ask yourself about your own practice design. I use these as often as possible and will prompt my thinking towards a more representative practice during the planning phase as well as during and after the session has happened when observing or reflecting.

Questions to ask yourself about your practice and score out of 5 (1= low / 5= high)

- Does the practice/objective detail specific purpose? What is the purpose?

- Is the present information (B.O.T.S.) in play what it is like in the game?

- Does the practice require the player to make decisions?

- Does the practice require the player to adapt their intentions?

- Does the practice require the player to adapt their movement solution (skill/technique/action)?

- Does the practice provide an appropriate level of challenge to the players?

- Are the practice dynamics, the direction, the timing and the force like what is required in the game?

- Does the practice induce pressure or emotional reactions to the player?

Conclusion

Looking back to Part 1, transfer in the context of sports training, refers to the gain or loss in the capability to perform a specific task as a result of practicing a different task. There are two main types of transfer: near transfer and far transfer. Near transfer involves training tasks that closely resemble the actual competition, facilitating effective learning and performance. Far transfer, on the other hand, involves practicing tasks that have significantly less of the key elements from the competition, making it challenging for skills to transfer seamlessly.

The effectiveness of transfer depends on several key elements in practice design. Representative information is creating a training environment that closely mirrors the conditions of the actual game, including factors like space, teammates, opponents, and of course, the ball. The role of the coach is to highlight the player’s attention and intention through guidance and prompting thought then observing the player while they calibrate their cognitive and physical solution independently. Action fidelity emphasises replicating the movements and techniques used in competition during practice. Affordance landscape involves creating a dynamic and unpredictable environment that allows players to explore various actions and solutions. Emotional context aims to simulate the pressure and risk experienced in a real game, fostering resilience and adaptability in players.

Two practice design examples, one for an 11 v 11 session and another for a smaller 5 v 5 + 2 game, are presented. These designs incorporate the principles of Constraint-Led Approach (CLA) to create a training environment that promotes near transfer by including representative information, action fidelity, affordance landscape, and emotional context. The goal is to ensure that players experience similar timing, direction and force in training as they would in an actual match, fostering adaptability and success in various contexts.

Bibliography

Correira, V., Carvalho, J., Araujo, D., Pereira, E., and Davids, K., (2018). Principles of nonlinear pedagogy in sport practice. Physical education and sport pedagogy, 24 (2), 117-132.

Ep.468 – Representative Learning Design & The Ecological Approach to Transfer of Training, Rob Gray, The Perception Action Podcast

Special thanks to Dr. Mark O’Sullivan for advice and feedback prior to publishing

Part 1: Straight from the training ground

Improving the transfer of learning from training to match day through practice design

Transfer in sports training is a critical concept that examines the extent to which skills acquired in one context can be effectively applied to another. This process is vital in the world of sports, where athletes strive to enhance their capabilities and adapt their skills from training environments to actual competitive scenarios.

In football, the discussion on transfer is nuanced, involving near transfer and far transfer. Near transfer is when training tasks closely resemble the match, with the aim of ensuring a seamless transition of skills. Whereas far transfer involves tasks that deviate significantly from the competitive environment, requiring athletes to adapt their skills to unfamiliar and dynamic situations. We will explore these differences and how this knowledge can guide our practice design.

This learning of transfer extends beyond the physical actions, it also encompasses the cognitive and emotional aspects of the game. The way athletes process information, make decisions, and handle the emotional context of competition is crucial in determining the success of transfer from training. Additionally, understanding the key elements that influence practice design is essential for coaches striving to create effective training environments.

What is transfer?

the gain (or loss) in the capability to perform the criterion task as a result of practice in the transfer task

In other words, increasing (or decreasing) the capability to perform in a match/competition environment (criterion task) as a result of practice within a training/practice environment (transfer task).

Types of transfer in training

Near Transfer

training close to match day representation involves transfer and tasks that are similar (or often nearly identical) to competition

This usually occurs when the practice design in training is similar in representation to the game, making the learning process the most effective for performance. Already having knowledge of the skills in football makes learning a new skills easier. Coaches can aid this positive transfer by making sure the individual builds an understanding of the similarities between the two movement solutions (skills) and the environments they perform them in (training or match). An example of this is a football player using their knowledge of 1v1 skills against live opposition in practice and then transferring that understanding and movement solution (skill) on match day.

Far Transfer

training that is far away from match representation involves transfer and tasks that are dissimilar from competition

Far transfer is when the process of learning a skill does not expose the athlete to a variability of stimulus and, as a result, when they are in an unpredictable and dynamic environment (a match), the skill will require a different response (movement solution). For example, when a football player learns 1v1 skills against a mannequin and then tries to put that into a match situation where the defender will use a variety of strategies and force to destabilise and attack the player in possession. Has the player on the ball been given opportunity to learn to be able to adjust and adapt their skills to get success in training?

Highlighting affordances (opportunity for action) and questioning intention is key for players to develop their knowledge in the game along with dynamic and challenging ecological practice design.

Learning skills is a continuous process always in motion. The process of learning a new movement solution will be adapted from actions, experiences and ideas from the past, e.g. exploring a new passing skill will lean into information attained from their own experiences, what they have seen and what the task is. In addition to this, the development of the skills will also affect the solutions previously learned when used in the future.

Practices are not categorised into either near transfer or far transfer, all practice designs will be somewhere on the spectrum above. We can understand that where our practice design might be is based on how many of the key elements are present within our practice design. It is unrealistic that all of the elements of a match will be represented as it is very hard to replicate a game environment due to the many variables. These include the crowd or parent pressures that the players will face, as well as the unpredictability of the opposition to name just two. However, there are factors that we can control, and, as coaches, it is our duty to be aware of this.

What is everyone else saying?

Common elements theory (Thorndike, 1931)

The determinant of transfer was the extent to which two tasks contain identical elements: the more shared elements, the more similar the two tasks, and the more transfer there would be.

Thorndike, E.L. (1931) The fundamentals of learning. American Journal of Psychology

Instance theory (Logan, 2002)

Skills are highly specific to the events experienced during training. That is, unless an event has been experienced during training, a response to this event will not be skilled.

Logan, G.D. (2002) Automaticity and Reading: Perspectives from the Instance Theory of Automatization.

Appreciating the research and work done over the years will guide and help our understanding of transfer from practice to competition. Leading professors play key roles in how our organisations shape the coaching methodologies at the elite level in both performance and development sectors of football. Therefore acknowledging the importance of the work Logan and Thorndike have done is impossible to ignore.

Where do these sit?

Below are some session plans, figure out where you would put them on our ‘Far and near transfer spectrum’ shown below.

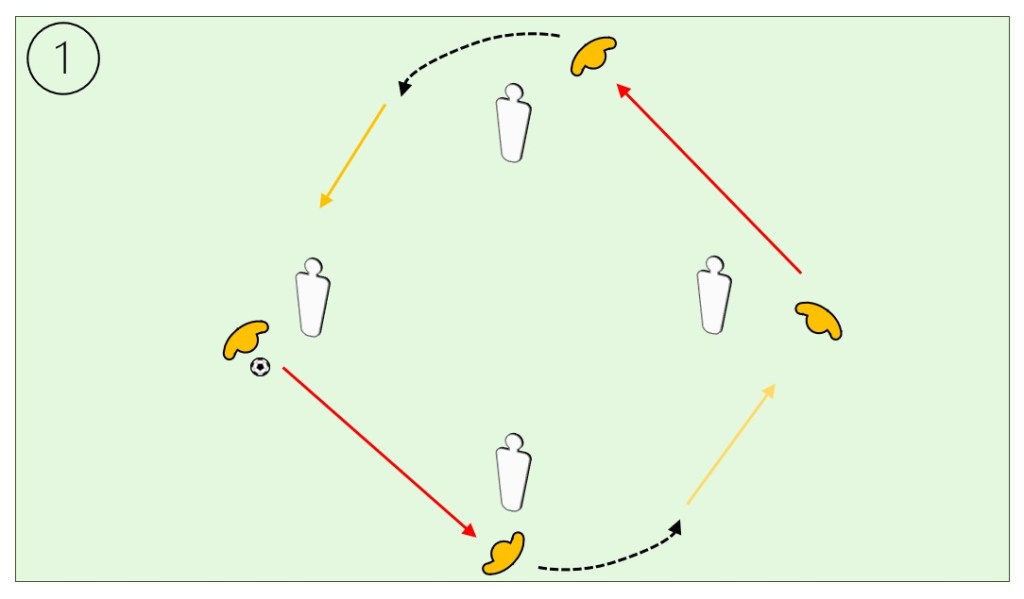

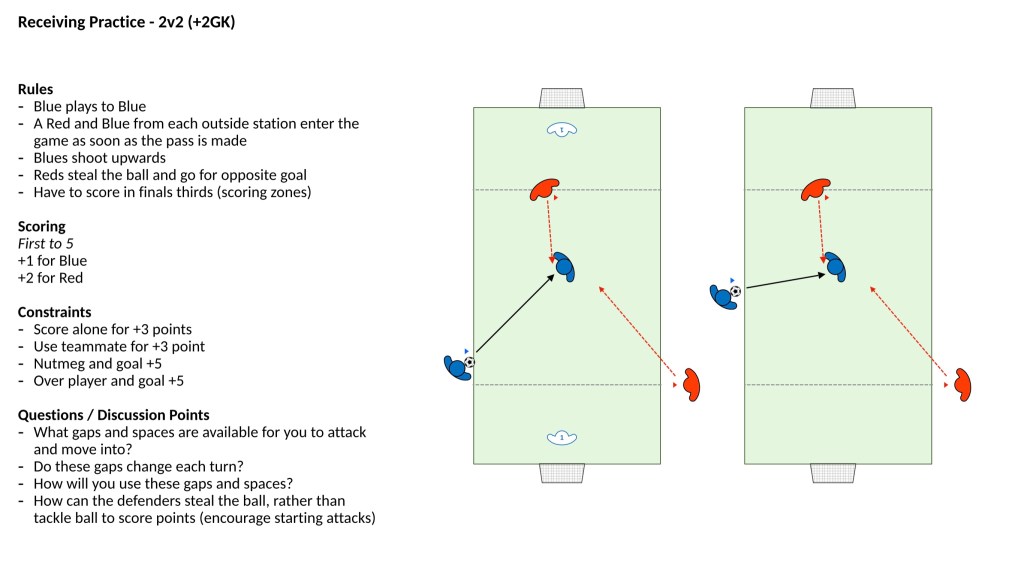

Practice 1 with progression – Passing Pattern

- Red line is the first pass / Yellow is the second / Green is the third / Blue is the fourth

- Players follow onto next mannequin

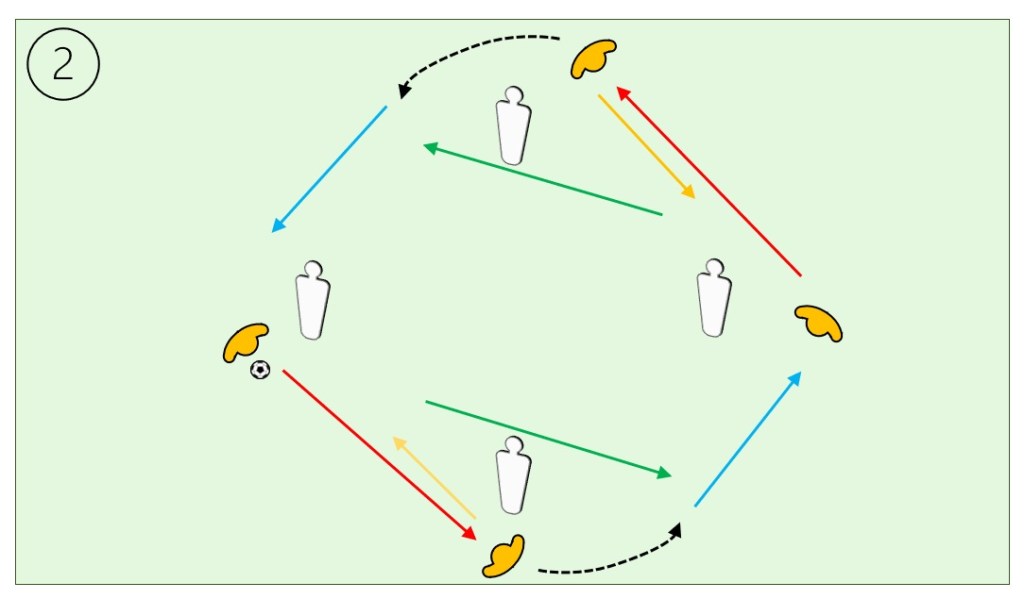

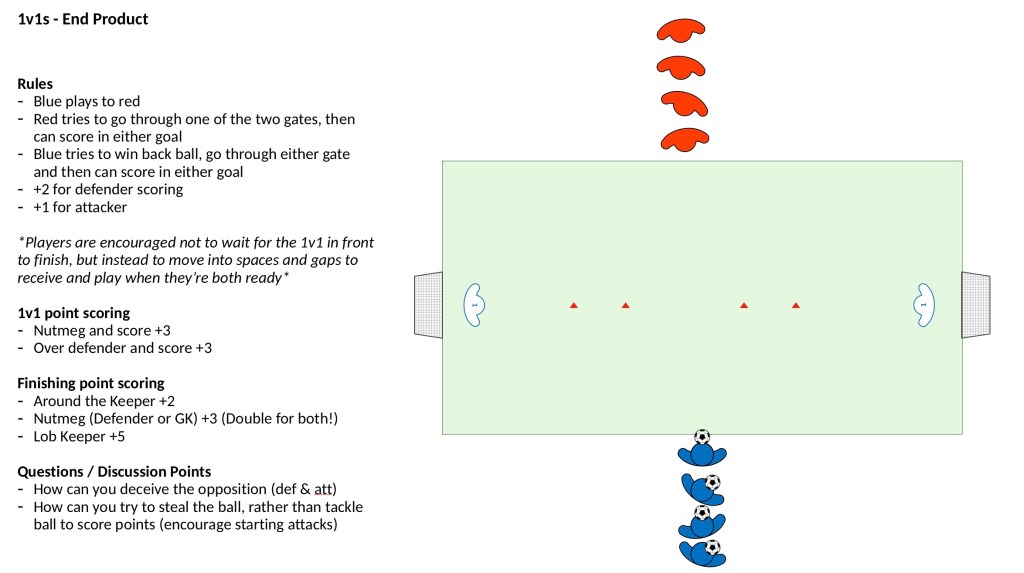

Practice 2- 1v1 to evade, entice or eliminate pressure

- White stays on outside / Blue vs Yellow in middle area

- Blue attack first and should try to receive from White

- If receive from White 1 they can score in either goal / If receive from White 2 they should score in opposite goal

- Blue stays attacking and Yellow stays defending / First to 5 goals for either defender or attacker then swap with pair from outside / Attacker should always receive the ball / Attacker should reset the 1v1 by exiting out the area each time

Practice 3- 5 v 5 + 4

- Blue vs Yellow in middle area with end zones

- Blue team defends end zone behind them and attacks into end zone in front (same for Yellows)

- Red players to act as end zone players either strikers or centre backs depending on which team is in possession and the direction they are attacking

- To score the team in possession must play into end zone players to unlock the mini goals in their attacking end zone

- Progression

- Use of marked out thirds and/or middle square to guide attention for playing into different areas

- Red players must assist 1st time or they play out for the opposition

Using our knowledge of the elements and principles for practice design to give the players near or far transfer, where would you put the practices above? Where would you put some of your own practices?

The players need to be a part of sessions that require adaptability and this can only happen within an unpredictable and dynamic practice that is near to competition. Players should not be given an answer so should be encouraged to explore and find their own solutions. Utilising trial and error, guided discovery and opportunity to reflect coaching strategies are key for players to build their knowledge in the game. There is not just one way to find success in a football match and no situation is ever the same. With this in mind it can help guide our practice design and the affordances our players will interact with by doing our best to try and replicate match day as much as we can.

Good decision-making in football relies on strong cognitive functions, particularly executive functions like response inhibition, cognitive flexibility, working memory, and attentional control. For instance, when a footballer intends to shoot at goal during a scoring opportunity but faces an unexpected change in the environment (a defender blocking or the goalkeeper moving), their ability when starting the action of the initial shot and adapting to the situation is crucial. Recognising the importance of these cognitive skills, sports organizations globally are heavily investing in cognitive testing and development as a key aspect of talent identification and development in football.

The premise is that footballers who are adaptive tend to excel on the field, and this can be developed over time. We are trying to design practices that offer the players opportunity to improve their cognitive performance but this can only be achieved through near transfer practice. Our role as the coach is to empower and highlight the athlete’s attention and intention so they can self-organise and try again.

Part 2: Straight from the training ground

What needs to be in practice design for transfer of learning

In the second part of ‘Straight from the training ground’ we will explore what is needed in practice design for near transfer to occur and how we can ensure our training has all the key elements of competition. We will also go in-depth around the 4 components for transferrable practices as well as a list of questions to ask yourself about your own practice to reflect and help guide your coaching on the grass.

Click here for Part 2: Straight from the training ground

Conclusion

Transfer in sports training is the ability to apply skills learned in one context to another, crucial in sports where athletes aim to adapt training skills to competitive scenarios. In football, near transfer involves closely resembling match conditions, while far transfer requires adapting skills to unfamiliar situations. Transfer extends to cognitive and emotional aspects of the game and this should influence practice design.

Near transfer, close to match representation, involves similar training to the game, enhancing effective skill transfer and cognitive development. Far transfer, distant from match representation, lacks variability, asking athletes to adapt skills in predictable situations. Practices fall on a spectrum between near and far transfer, influenced by key elements. Coaches should aim for adaptability in sessions, utilising trial and error, guided discovery, and reflection for players to develop game knowledge. Football decision-making relies on cognitive functions and near transfer practice design is imperative to improve a player’s performance. Ensuring our practices have as many of the key elements represented as possible.

The goal is to design practices for near transfer, empowering players to improve cognitive performance through self-organisation. Coaches play a vital role in guiding attention and intention for the player and giving time for the athlete to calibrate and adapt these, replicating match conditions as closely as possible to enhance player adaptability and success.

Bibliography

Logan, G.D. (2002) Automaticity and Reading: Perspectives from the Instance Theory of Automatization.

Thorndike, E.L. (1931) The fundamentals of learning. American Journal of Psychology

Fransen, J. (2022). There is no evidence for a far transfer of cognitive training to sport performance.

Learning cannot be efficient

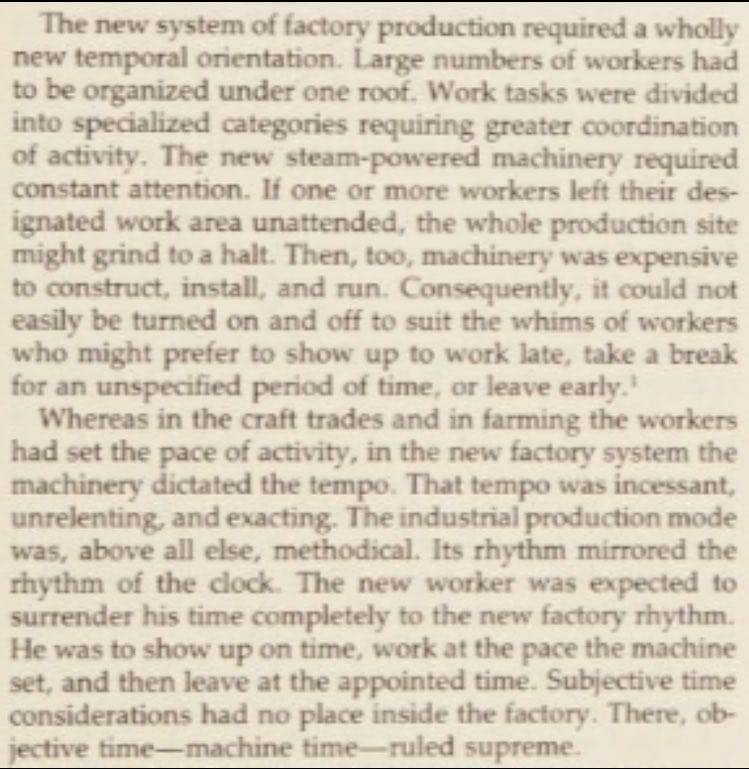

Why the demand for timed practices removes equity to learn in football

In the world of football coaching, there is a growing concern that the pursuit of highly organised sessions with timed and blocked practices may inadvertently hinder the learning process and limit the development of players. The belief that fast-paced, blocked practices are the key to success can undermine the equity needed to nurture a player’s skills effectively. In this article, we will explore why the demand for timed practices can remove equity from the learning process and how a more ecological approach can foster true development in football through understanding modern research and how society has shaped our expectations.

Equity vs. Equality

To achieve true player development, we must distinguish between equity and equality. While equality means providing everyone with the same resources or opportunities, equity recognises that each player has different circumstances and requires unique resources to reach a similar outcome. In football, this means tailoring coaching methods to suit individual needs, rather than applying a one-size-fits-all approach.

Taking time is better than time taking

Blocked and timed practices removes the equitable development of players. Each player is unique and progresses at their own pace. Some players may grasp a concept quickly and require additional challenges, while others may need more time to explore and understand. Timed practices fail to account for these differences in player development. Too often coaches have a highly organised session plan with clear timings for each section and they will follow this no matter where the players are in their learning. The skill of the coach is to know their players to a level where they can see and identify where they are in their understanding, noticing knowledge about vs knowledge in (of).

Below is one of our article where @jacobeliotpickles explores this topic: