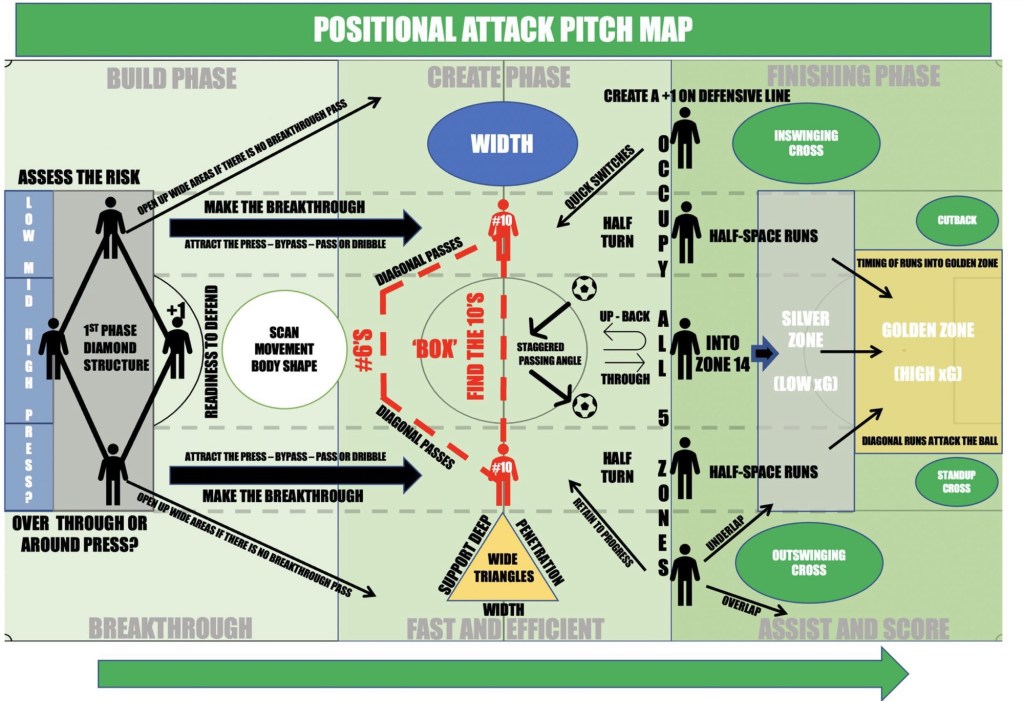

If you’ve ever worked in football development, you’re probably familiar with the concept of the pitch divided into thirds: Build, Create, and Finish. These three words have been drilled into us for decades, forming the backbone of countless game models, curriculums, and footballing philosophies. Often viewed through a positional lens, even the England DNA framework leans heavily on these principles.

But is this approach actually stifling the development of our young players?

The idea that a player can only “create” once the ball reaches the midfield or “build” solely within their defensive third is, in my opinion, deeply flawed. It curbs the potential of creative defenders who thrive on making bold plays from the back, as well as attackers who relish opportunities to contribute deeper in the field.

Take a closer look at most academy sides in England, and you’ll see defenders endlessly recycling possession in their own third, missing clear opportunities to bypass lines and exploit space. The rigid adherence to this linear model does more than limit creativity—it dulls the game.

If we must simplify an inherently complex and dynamic game for ease of understanding, we should rethink the current model. A player’s decisions shouldn’t be dictated by where they are located on the pitch, but by the unfolding realities of the game itself. Players are often given one set of answers through a positional game model, and are unable to explore the game in their own unique ways.

As coaches, we need to recognise the difference between how we see the game and how players experience it. Development isn’t about forcing players into our perception of how the game should be played and if we truly want to produce world-class players and coaches, we must begin to see their version of the game, through their eyes. We must view them as individuals—not as positions within a rigid game model.

The Price of Conformity

Most of a coach’s time on the pitch seems to be spent creating patterns and helping the team to build an attack. But every game model I’ve seen misses one crucial step: Identification. Who are the individual players on my team? Who are the individuals on the opposing team? And how can we exploit weaknesses to score and win the game?

This integral step is glaringly absent from most game models and philosophies. Instead, it’s replaced with a rigid, fixed team identity that takes little account of how the opposition plays or what the unique qualities of individuals on both sides bring to the game.

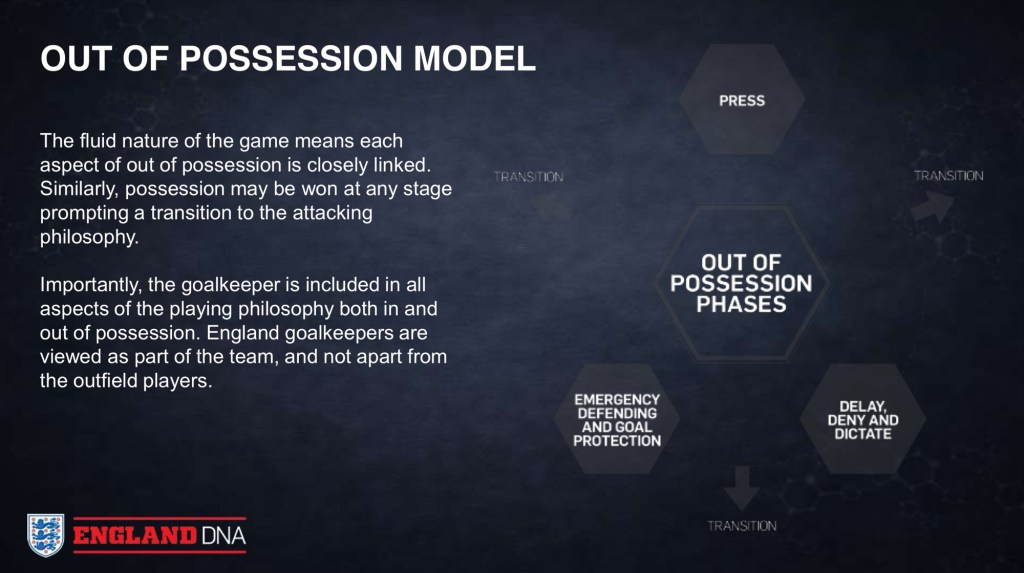

Take, for example, the England DNA model for coaching players out of possession. The first thing you see is press. All good and well—until a player like Harry Kane comes along. So now what? These linear breakdowns of football philosophies lead to forcing square pegs into round holes. If this structure can’t support the qualities of England’s all-time leading goal scorer and current captain, what other talents are slipping through the cracks?

We’ve all heard the excuses: “He can’t get around the pitch,” or “She can’t press.” How many exceptional footballers have had their development stunted simply because they didn’t fit into a rigid game model? On the flip side, how many players have been given opportunities—not because they’re great footballers, but because they can run around and press, just as the game model demands?

These frameworks destroy more than they create. It’s painful to think about how many quality players with unique skillsets we may have lost.

So how do we go about making sure we support the development of all types of players, not just one type created by rigid game model.

The FA’s England DNA ‘Out of Possession’ Model

Build, Create, Finish

One way we can do this is with our session design. When we typically design a practice, we will look at what we want the team to learn, and fit an area size which is deemed relevant—often using relative pitch dimensions. Now this seems logical, however if we look closer, this will often lead to players attempting to exploit static space in the same ways over and over.

What I suggest is to constantly move the area boundaries of the practice. So players have to continuously problem solve working in different spaces on the pitch. When we say that the pitch is a particular size, so we’ll work in a similar area size in training, we forget that there are often moments in the game where, despite the full size of the pitch, the full use of this area is not available for the the players around the ball to use.

The game is so dynamic and variable that spaces open and close continuously, so with that in mind, do we recreate these ever-changing spaces in our training sessions?

I would also advise moving away from realism in this aspect and begin to create extremes. This is to exaggerate the space, or lack of it, to the players, then our players will need to quickly reorganise, constantly finding new solutions, and in turn, using more of a variety of skills to overcome the problem of ever changing space.

Despite this not being realistic in terms of a static pitch size, it is realistic in training the ability to adapt to ever changing spaces.

Alignment or Agreement

When a coach first steps into a professional academy, they’re met with a philosophy and a game model. They’re told that all teams must be aligned in their style of play—to all look the same. This, however is not alignment, but agreement. If we are truly and holistically developing individuals, no team should look the same.

Every team, every age group, and every individual brings something unique to the game. The first step should always be identifying who your players are: How do they like to play? Who inspires them? What makes them unique?

Once we understand that, we can build teams around these individual strengths. Each team would become unique. Each player would feel seen and valued, developing into the best version of themselves—not a limited version molded to fit the system.

Players should also learn to evaluate their opponents: What are the weaknesses in the opposition? How can their strengths exploit those weaknesses? Imagine shifting from “play through the thirds” to “Their back line is high—how can we exploit that?”

The game is not simple; it’s complex. Yet, we often teach players a linear, oversimplified version of football instead of equipping them to analyze and adapt in real time. As coaches, we owe it to our players to truly know them: Who are they? What do they love? How do they play? Who are their role models?

Only when we embrace their individuality can we develop them into the best versions of themselves—not the watered-down versions we impose through rigid systems.

When building a practice, we must not aim to develop players who play one particular way and use a limited set of skills, but look to develop adaptability and allow for a wide variety of skills and techniques.

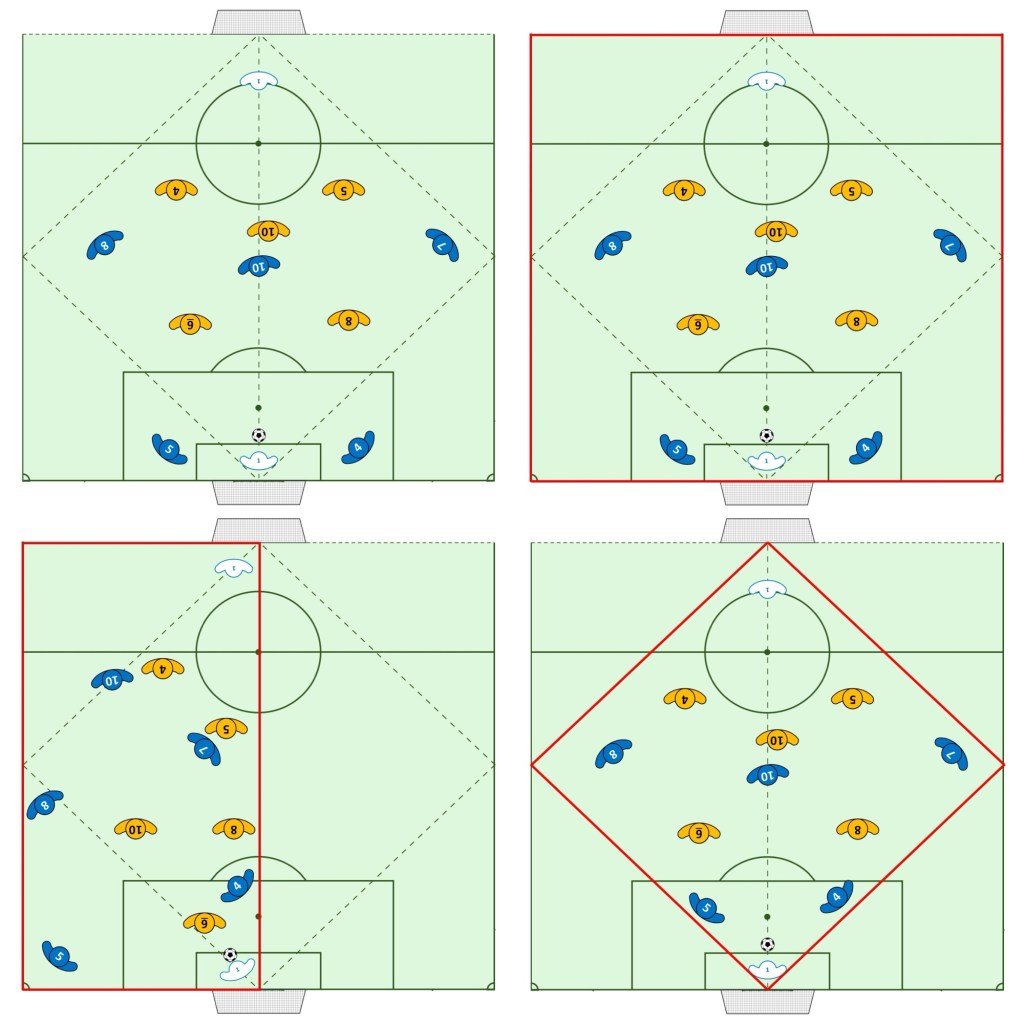

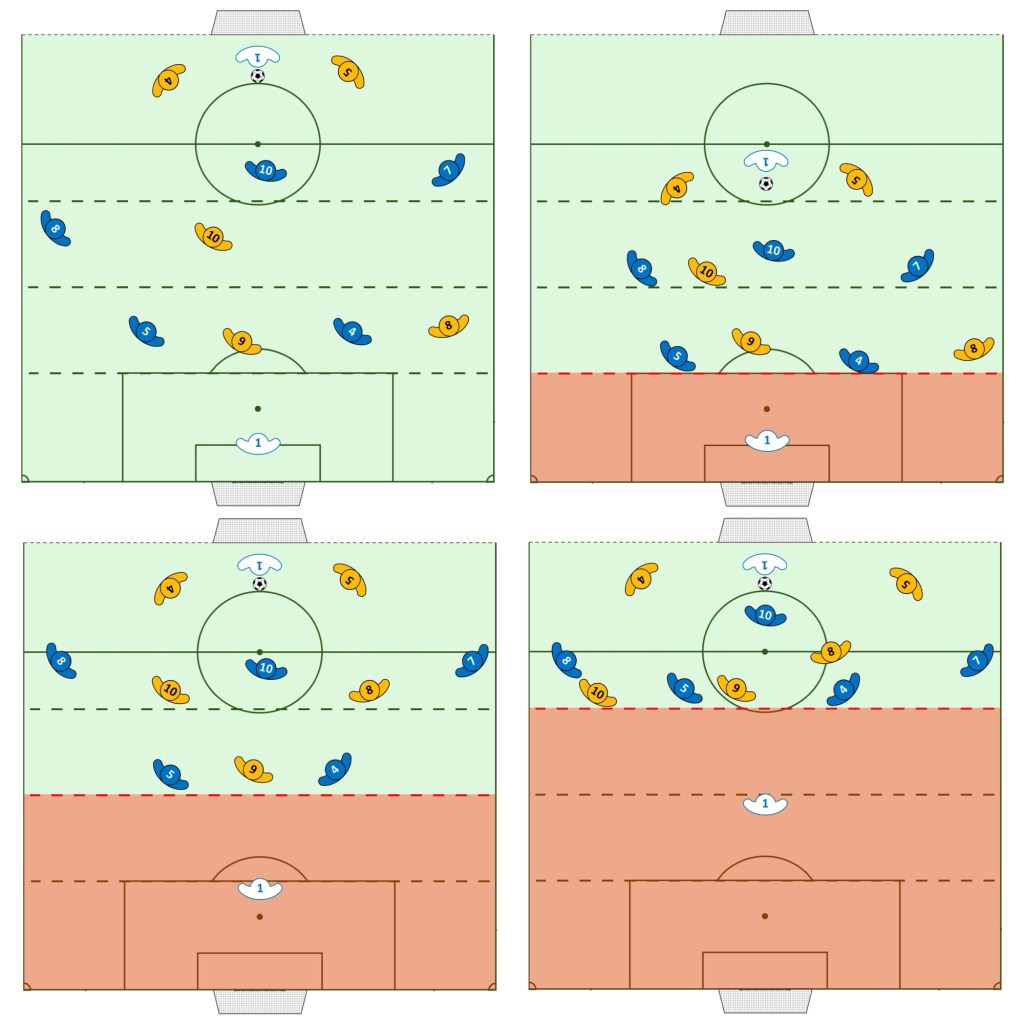

The image below shows a practice designed [by Aslan Odev] to draw attention to the opposition’s back line. By constantly changing which backline the players are using, they have to constantly readjust dynamically within the game, and find solutions to the ever changing problem. Within the practice, you will see players building, creating and finishing. Similar to the game, they are one and the same.

The Way Forward

Football isn’t a series of boxes to check—it’s a dynamic, unpredictable game that demands adaptable players and coaches. The best footballers in the world thrive because they bring something unique to the game, not because they conform to a predefined mold.

It’s time to abandon rigid structures and embrace the messy, creative, and individual nature of football. Only then can we truly unlock the potential of our players.

very informative and insightful jake! Keep thinking out of the box and churn out more thoughts like these!

LikeLiked by 1 person