Control

Is our addiction to control destroying our most creative players? It seems we may have strayed further than a simple need for control of the ball; we want to decide every single moment, every movement, every position, every thought.

We want to control the player and their every move. Only, controlling each player’s actions comes at a price. We lose their perception of the game and, therefore, their identity and creativity in the process.

But where does our cry for control come from? We’re going to explore if positional play is the answer to developing creative and unique footballers, what the alternatives are and how to train players to think for themselves and find unique solutions on the football pitch.

Positional Play

So let’s start here, what’s wrong with positional play (PP)?

Positional play decides what the players do and when they do it. You may hear that through PP we give the players freedom within the rules we enforce, however, this is no freedom at all, for we have predetermined the answers from which the players can choose. This is not freedom, but an illusion of such.

Essentially, positional play attempts to maximise efficiency by limiting the player. The player must stand and occupy spaces on the pitch to affect the opposition’s defensive system, and then after receiving the ball, the players have a set of options from which to choose.

And through the rule of occupying predetermined spaces, we remove freedom of movement and therefore the freedom to create spaces through creative, spontaneous play.

So, when it comes to development, what exactly is the problem? Well, a PP system is ultimately decided by the coach. The system comes before the individual. However, if we are so determined to develop unique individuals, individual development can’t come second.

Being part of such a rigid system has many drawbacks, especially within the paradigm of development. There is no freedom of expression for the player, no original thought. The players become robots, they lose themselves. We stop our players from developing a unique identity. They lose what makes them special. We make them like everyone else.

And what’s worse is, this style of football, which hinders a young player’s development, is rife within the academy system and is spreading to grassroots. We have to ask ourselves a fundamental question, when it comes to development, what do we want to see?

A system which shows off some of our knowledge as coaches and will limit our players?

Or, a system built around the individuals within the group, allowing them to make decisions on how to build, how to create and how to score. A style of play which will likely empower and encourage new and unique ideas.

I know which one I’m after. And through modern interpretations of practice, if we break free from the norm, there is another way.

Pawns

The honest truth, though we may not want to hear it is this; positional play is a style of play to show the ego of the coach. The coach picks when and where their team attacks, which actions the players can take and ultimately limits the player’s decisions. It’s to show the knowledge of the coach, not the knowledge of the players.

One of the many problems with this approach is these predetermined attacks are scripted and once another team has seen the script, it becomes easy to stop. And if this rigid plan is stopped, then the players look around not knowing what to do until the break when the coach can take over again and offer them a new solution.

This is not how we are going to develop creative, intelligent footballers and if this has been a player’s whole football education, they have no way to adapt, to find a new answer, to find a way to succeed. The honest truth is, we set them up to fail.

It’s becoming increasingly more frequent to hear the comparison between football and the game of chess. In chess, there is a chess player, who dictates the movement of the pieces. The pieces have fixed movements, and when can these pieces move? When the master decides.

But there’s a fundamental problem here, footballers are not chess pieces who can’t think for themselves and they do not need a chess master to govern their movements. In chess we give life to static objects by giving them purpose – rules in which they can move. In football, we’ve limited human expression into lifeless objects who are bound by the limits we enforce.

We limit our players into behaving one way, that suits the system and through this we lose individual character and creativity. This stems from two things, Pep Guardiola being extremely successful with his positional brand of elite football and our very own fears and insecurities.

We want control, our image on the pitch, our vision, we want to show what we know – but in this quest to show our own knowledge we’ve lost what is most important, the development and the knowledge of the player. This is, of course, the very essence of a development coach.

Freedom

We must remember that when controlling possession, building from the back and playing through the thirds there is not only one way to attack. Just as high pressing is not the only way to defend. These styles of play are not necessary to win games of football, nor are they necessary for the development of world class footballers.

You could argue that moving the ball more, having more possession will allow for more interactions and therefore more technical and skill based development.

I too believe more interactions are beneficial, however, this doesn’t mean we should enforce one version of possession football onto our players. Some of us might like shorter passes, players closer together for more interactions, however, in development, we don’t want to undervalue the long pass, we don’t want to undervalue stretching the opposition.

We must be open to all opportunities to attack and defend, and our job is to highlight these opportunities to our players, not instruct them. And it is for our players to take this information and act upon it however they see fit.

Only then will real development take place. This is the safe space we must create, where the players can try things we wouldn’t, and work things out for themselves. I can honestly count on one hand the amount of coaches at the top level that actually do this.

The Constraints Led Approach (CLA) constrains, manipulates and stretches the boundaries of practice to highlight problems the players may face in the performance environment (game day).

However we must be careful not to over constrain, or only highlight one aspect of the game. I have been working within the world of the CLA for almost a decade now, and something I have come to realise is that change and variation within practice is where the real learning happens.

Schöllhorn

Differential Learning

As my understanding of development and learning evolves, I am increasingly intrigued by Differential Learning. Differential learning is a motor learning method that was proposed in 1999 by Dr. Wolfgang Schöllhorn, and works around the premise that the learning of an action or movement is dependant on the amount of noise created (practice variability).

As discussed in a previous article written for theRaumdeuter, ‘We need to talk about technique…’, our aim as coaches should not be to reach for ‘the one perfect technique’, but instead for skilful adaptability. In other words, rather than perfection of particular techniques, we should aim for a wide range of variability of techniques – the idea is that this approach will lead to players being so adaptable, that they can overcome any problem put in front of them.

CLA & DL

Whilst I promote the use of the CLA and DL, it is important to understand that there are differences between the two and how we use them will determine how our players develop. Here are the main differences that have made an impact on my understanding:

DL

In DL, the idea is to create enough stochastic resonance (aka. noise/variation) as to not engage the frontal lobe of the brain.

The problem with engaging the frontal lobe, is that this is the part of the brain that plays a role in judgment, empathy and reward seeking behaviour and motivation.

Judgement, in football development terms, will lead to behaviour that will lead the athlete behaving in ways that will interrupt the learning process. For example, if an athlete attempts to dribble, and falls over losing the ball, they will feel judgement from their peers to maybe not try again.

Many of the brain’s dopamine-sensitive neurons are in the frontal lobe, dopamine is a brain chemical that helps support feelings of reward and motivation. So if the coach says something like, ‘Mujeeb, well done for switching the ball out of trouble there.’ This will engage the frontal lobe, the player will feel a positive hit from the dopamine, and begin to behave seeking more of the same reward.

Now Mujeeb will begin to behave as if tight areas are perceived as ‘trouble’ and big spaces afford the most opportunity. (What we will look at later is how there is opportunity in every situation on a football pitch) So if we praise a player blindly, it can lead to poor decision making in search for dopamine.

With empathy, maybe a player shoots and misses the target, there is a free player in the box who feels the ball should have been played across to score. The player will feel empathy for the missed opportunity and this will shape how they approach similar problems in the future.

We want to avoid engaging the frontal lobe in practice so the player will stay in a continuous process driven state. We do this through constant variation of the task, environment and individual boundaries. The athlete is to learn without correction or feedback. This is essentially Differential Learning.

Think of a baby attempting to walk, when they fall over, the frontal lobe has not reached the stage of feeling judged, so they just get back up and try again. They are in a constant state of process, a constant state of learning from within their own experience. This is the state that DL attempts to reach.

CLA

The CLA works on the premise that you can manipulate the task, environment and individual constraints to highlight a particular part of the game. The practice will offer affordances (opportunities to act) in line with the constraints you set, however the difference is these constraints are not changed as often. It is common to see a CLA practice’s constraints remain until the athletes find success.

These constraints, if left without constant change, will engage the frontal lobe, giving the players time to feel empathy, judgment and reward seeking behaviour.

Isolated Practice

The CLA requires representative design, the idea that for a representative practice, you need a ball, direction, an opponent and consequence. Where this breaks down is that there is no space for isolated practice. When looking through the lens of the CLA, isolated practice is not representative, and leads us to believe that there is no skill acquisition available within isolated practice. The problem is, we cannot say for sure that isolated practice does not contribute to an athlete’s skill acquisition at all.

Where DL differs, is that the method does not require opponents to support the athlete in learning. All it suggests, is that you need constant variation to not engage the frontal lobe.

Take an unopposed passing practice for instance, the practice itself offers little in the way of motor learning. However, through the lens of differential learning, it does offer something. There is often little to no variation within an unopposed passing practice, but, why do some coaches swear that it develops certain skills in players?

Because it actually does. But not for the reasons that coaches are often led to believe. One thing that the CLA and DL have in common is that repetition to reach a perfected technique does not improve a player’s skill level. Actually, through the ages of growth is where we see most improvement with drills like this, not because of the practice, but through the variation caused by growth.

In fact, doing almost anything with a ball whilst going through periods of growth will cause enough stochastic resonance to help the player learn. Whichever of these lenses we look through, this type of practice really is the absolute bare minimum when working with our players, I would absolutely advocate for using these as little as possible when compared with CLA or DL practice design.

Finally, there is noise in the CLA, there is variation, enough for players to develop much more than traditional coaching methods. However, if we want to develop the best and brightest footballers in the world, I think we can and should go further.

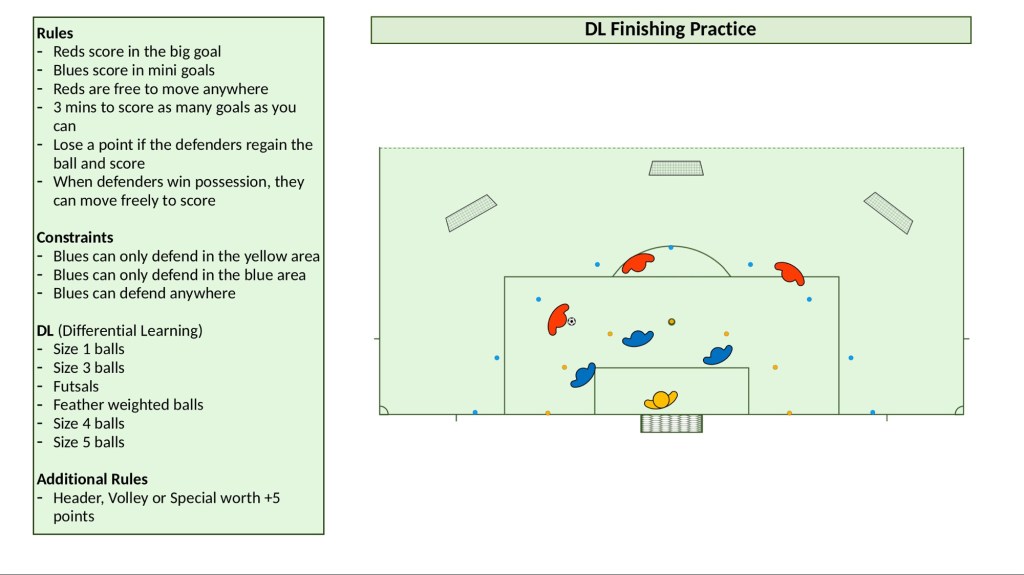

DL Finishing Practice

So what does a team based DL practice look like? Let’s look at finishing. Traditionally, finishing practices contain very little variation. Below is a finishing practice designed to add tonnes of stochastic resonance/noise/variation. You can adapt the rules of the practice as you see fit for your players. You adapt this practice easily to incorporate more or less players.

You can even do this with one attacker and no defenders, although there’ll be less stochastic resonance than what we would ideally search for, the variation from the different types of balls will support your athlete’s finishing development.

The idea is that the defenders are locked into zones to block, they can tackle if the ball enters the zone they are currently occupying. Again, the idea is to not engage the frontal lobe. So change the area size frequently.

What you are likely to find is players adapting in real time to the different environmental challenges from the balls and the opposition’s constraints.

I have been guilty myself of only highlighting one problem through the CLA, asking the players to repeat the search for a solution to one particular problem. And through this misunderstanding of practice design, I found that this isn’t enough to develop players to reach their highest potential.

For example, what happens when that problem inevitably changes on game day? We’ve practiced playing against a back four, now they’ve changed to a back three. The players become lost, and we have to step in to ‘guide’ them through a problem they’re not equipped to solve.

So, this begs the question, how do we develop individuals who can dynamically seek out deficiencies in the opposition? Who can identify where the gaps are appearing and how to create their own gaps to exploit. And how do we train this? Rather than the players following a rigorous set of rules, can we develop them to think for themselves?

Thankfully, yes we can. Below is a carefully constructed practice which helps develop player’s awareness and creativity. (Whilst viewing these practices, it’s important to understand that we are not looking through the lens of positional play, players do not have set positions they must occupy, but rather their positions are to be taken off of the position of the ball and the opponents.)

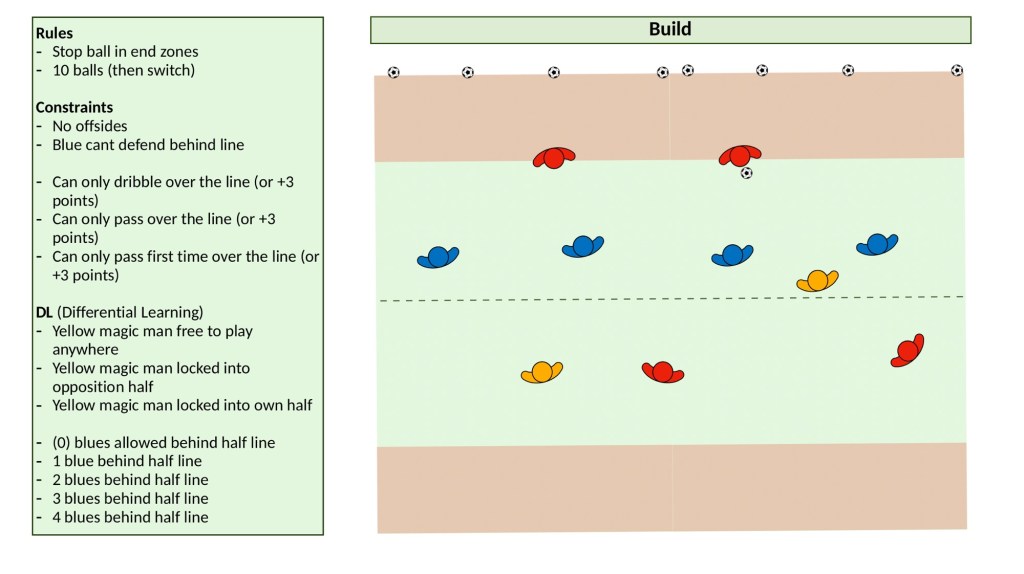

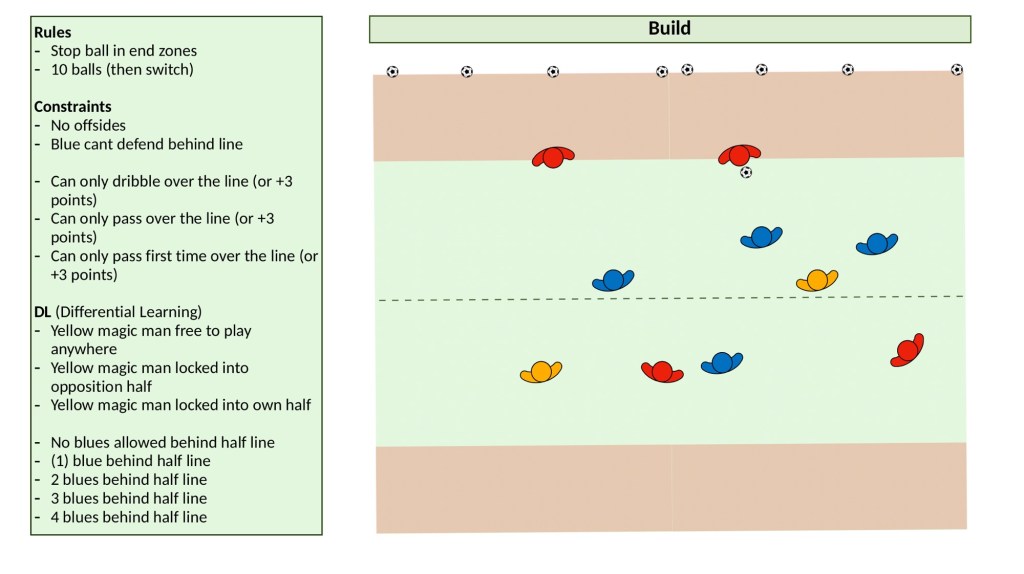

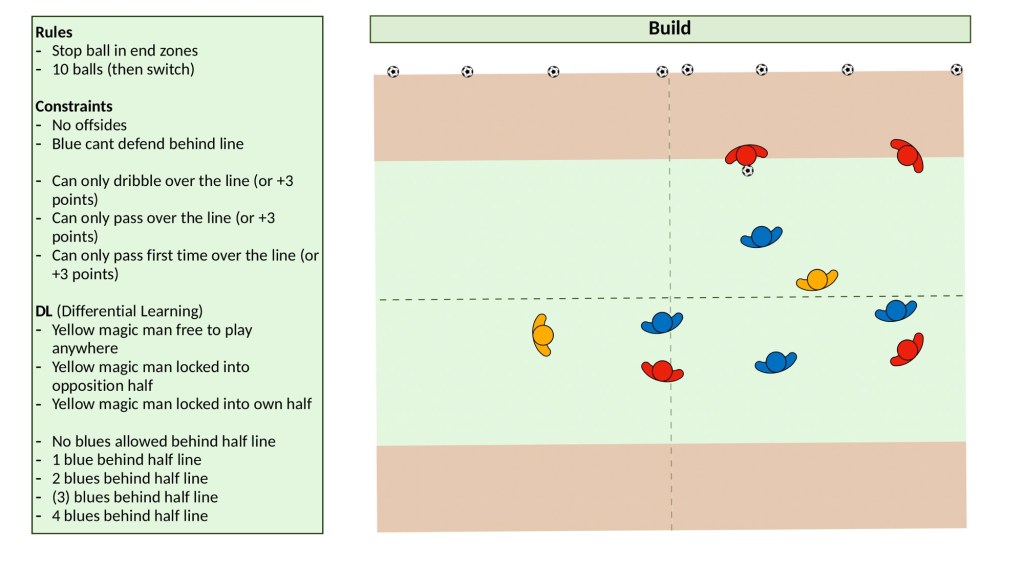

Build and Break

Below we will show a ‘build and break’ practice, designed to help players break apart basic defensive structures, in order to progress into more attacking spaces. This practice can be tailored to all age groups and any number of players. The rules are simple, get the ball from one end zone to the other.

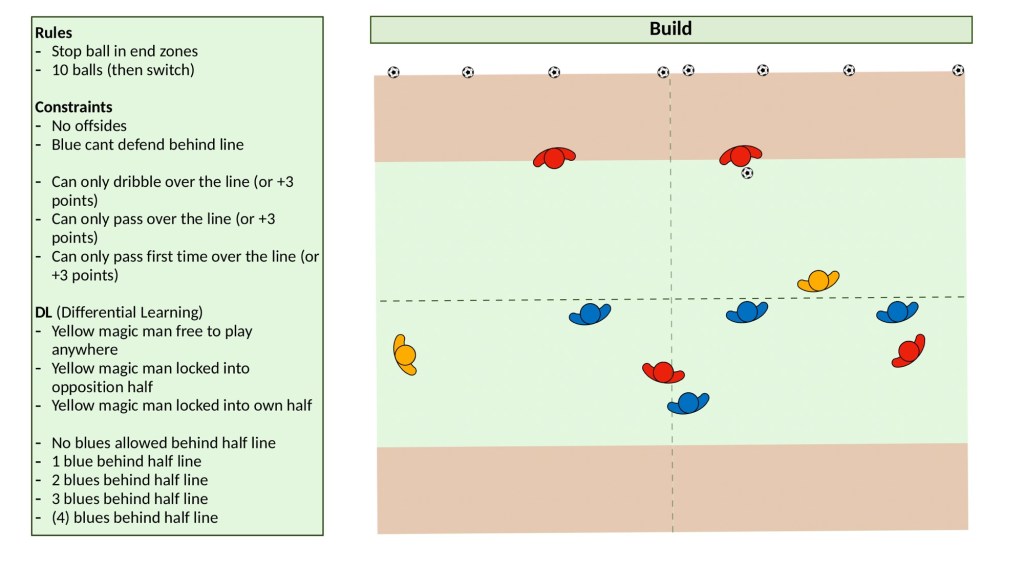

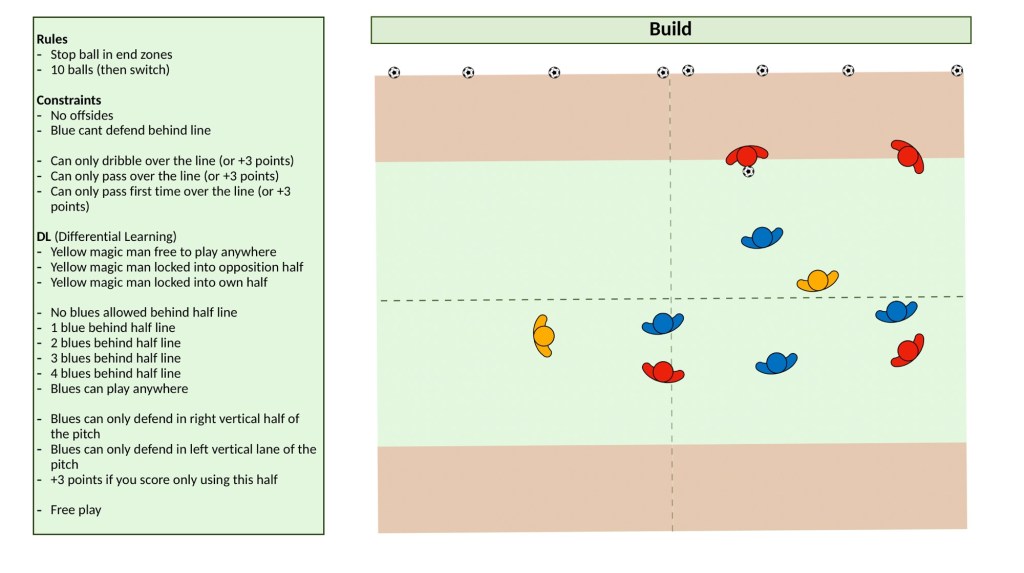

The difference? Below pictures of the same practice with different constraints/boundaries being applied. The first constraint is that the blues can’t defend behind the halfway line. This will make them defend in a certain way, forcing the attacking team to act.

This is a keystone in constraints based coaching, constraining to afford. Essentially constraining the defenders so they act in a specific way, and therefore your attackers will act against that. As you scroll through the practice designs, new rules are applied; now one defender must defend behind the halfway line, then two, then three and so on.

Rather than just playing vs a defensive four, or a defensive two, the idea is to constantly change the opposition so the attackers have to self organise and work out solutions to new problems in real time, in game. These boundaries are to be changed every minute or so, this gives the attackers no time to relax and they stay in a constant state of problem solving, or as Wolfgang puts it ‘stochastic resonance’. This is what we are searching for, this is the developmental sweet spot.

Now, when it comes to game day, the players should be able to see and act upon whatever is in front of them. The idea is to ask them to constantly solve ever changing problems without the need for anyone to decide how to overcome these problems for them. Our job as the coach? Become obsolete.

There are also additional rules above, such as ‘Blues can only defend in the right side of the pitch.’ Again, this will change how they defend and this will then change the behaviours of the attacking team. These rules are ideas to constantly change the environment.

All of these rules are to be added gradually, and changed often. Allow some free play as part of the block as well.

We may feel it necessary to allow short breaks for the players to discuss how they’ll overcome these problems. One nice idea is to give each team a ‘time out’ they can use in each block at any time. If we give them more than one time out, I think it’s important to make these shorter each time so they have to be very deliberate with their communication.

Now all that’s left is to sit back and observe how our players attempt to overcome these problems, be careful not to go in and ‘fix’. Observation is key. We must get to know our players and how they approach the problems set. I’m often surprised with what some of them come up within this chaotic form of practice.

Opportunities to Act

It’s important to recognise that most of the hard work as a coach is done in the practice design. There is no need to constantly move in and force our opinion of how the game should be played when developing our players.

If we create a rich environment, full of opportunities to act, our players will choose how to solve these problems without much need for us to step in, we are simply there to bring their attention to these opportunities.

Observing is the best thing we can do, then asking our players to consolidate their learning; ‘Teddy, I’m interested as to why you chose to do that in that situation, could you explain why you made that decision?’

In highlighting their attention to things you can see that they may have missed. ‘Sarah, I noticed something when you had the ball just now, did you see Toby in a lot of space on the right hand side? You don’t have to give him the ball, but just be aware that he keeps taking up some good positions.’ Sarah may decide to use Toby, she may decide to fake using him, or ignore him all together – ultimately, it’s up to her.

What we are trying to avoid here, is everyone using Toby in the same way. How every single player approaches each problem will be different and that is exactly what we’re after. Individual thought.

Now we’re a part of their learning. We’re helping them see, highlighting opportunities to act, but not telling them they must act in a certain way. We are collaborating with them. All that’s left to do is sit back and watch the cogs turn as they become more ‘attuned’ to their environment.

And remember, there are no RIGHT answers. To be able to coach this freely, without the shackles of right and wrong, we might need to bust some unspoken footballing myths.

Myths

To break free from the constraints of control, first we must destroy the unspoken myths of modern day football…

Switching Play: Switching play is a regular theme of practice within academy football. The internet is riddled with ‘switching play’ practices, all with the same basic message. ‘Get the ball away from the chaos.’ But, what if by moving the ball away from the opposition, we are also moving the ball away from opportunities to play and create?

There is no need to switch the ball out of tight situations. There, I said it. When players are free on the wing, we think that we need to switch the play away from the rest of the team and put our winger or fullback in a 1 on 1 situation alone on the other side of the pitch, regardless of if they are a 1v1 player or not.

We’ve all heard shouts such as ‘switch it!’ from a coach on the sideline, then a player ignoring that instruction, faking playing wide and creating a new opportunity to play forward in amongst the chaos. The coach then claps and tells them well done, despite two seconds ago demanding that the only possible answer was to play the ball ‘out of trouble.’

There is absolutely no need to switch the ball out of a tight situation, it is one of many options, but not the only option. Some players may be able to play through that tight area with clever fakes, dribbles, passes and touches. We must allow our players to explore all the options, not just one. Within chaos, there is also opportunity.

Maximum width: Maximum width is not necessary to create space in a game of football. There is a place for stretching the opposition – pinning back the fullbacks, and keeping the width in order to create gaps in the opposition to play through.

It seems logical, and as PP systems have evolved, they have had to incorporate a strong rest defence to cope with the loss of possession into spaces created by having our players so far apart and far away from the ball, this has birthed the rise of the inverted fullback. However, none of this is strictly necessary to be able to play controlling and attacking football.

Every coaching course you attend points to maximum width as an integral principle of the game. When nearly every coach steps in on match day, you will undoubtably hear the phrase ‘where’s our width?’ Or ‘make sure we’re high and wide!’

However, when you begin to look closely, this often hinders the players more than it helps them. I’ve often seen these rules demanded from players, and they stand there, lifeless, just waiting. They’re not involved in the game, and unfortunately, following strict instructions will not help them reach their full potential.

Just like with switching play, there is no need for having one player hug the touch line. Maybe if you have a player who likes to isolate 1v1, but as a general rule? Remember there are no rules, players have to be free to find what works for them. The players must be able to explore options other than one style of play.

How often, for example, have you seen a player attempting to move into a central space to receive a forward pass, and is immediately told they must create width for the team. Now the player has lost their curiosity for dynamic spaces. They now just stand where they’re told. And just with that one phrase, their curiosity is gone and so is their potential. What if they found a new space inside the pitch, got on the ball and created a scoring opportunity for their team? We’ll never know.

Relativity

So what’s the alternative? Well it doesn’t have to be so black and white. If you want to create gaps in the opposition, do you NEED maximum width of the pitch? Can you not create enough width around the opposition? What about minimum width? What would happen if we changed our coaching philosophy to incorporate relative width? Taking position off of the ball and the opposition?

We have come to accept that maximum width is a set principle in football. It is not. There are no rules. When the development of the player comes to the forefront, I say that the players should decide. And when we speak about the development of young footballers, they are being hampered by this over simplification of the game. Maximum width should be a choice of the player for a reason. If they can not make that choice and we make it for them, we are cheating them away from their full potential.

Let’s start a new principle: ‘Play where the ball needs you to be’.

Creativity is only needed in the final third: ‘Wait for the ball in these spaces and we’ll move the ball to you’: Another positional play principle. Stand here and we’ll get you the ball. Think about all the interactions you instantly kill by forcing players to do this. I’ve seen it with my own eyes, players wanting to drop out of midfield to pull an opposition midfielder out, creating gaps to play through. Instead, no, stand in there and wait.

We talk about creative players as if they only ever belonged in the final third, every player on the pitch should have the responsibility to create. Why can’t a centre back be the most creative player on the pitch?

We forget that creative players can exist all over the pitch. Players that were ball orientated. We kill them before they’re even born. ‘Stand here and wait for the ball’, is by far the worst phrase in football development. We tell the players how they should build, how they should create, how they should attack. What about the players that can create the opportunity, not to score or assist, but what about the players who can create the opportunities to build?

Break Free from the Shackles

When we set up a practice, it’s important to think about whether we are allowing the players to explore all of the options the game has to offer or whether we’re just imposing one way to play onto them.

When we hear someone say, ‘you must be high and wide!’, or ‘where’s our width?!’ Ask them ‘why?’ What about the opposite option to that, what about everything in between?

We must stop accepting these make believe rules as truth and begin asking your players to explore the game. Maybe they’ll come up with something we have never seen before. Something new, something organic.

Turn up the Noise

More noise, less structure. You want your players to build out against a front three? Ask them build out against a front 3, 2, 1 and 4. Watch, as every few minutes you change the opposition shape, they begin to solve new problems together. Watch the team work together and the new ideas unfold.

They’ve solved playing out against all of these different formations? Change the pitch size: Narrow, Long, Short, Wide, No Corners, No middle.

Change the task, often: Build without going around the opposition +3 points, build without going through the oppostion +3 points, Build without playing over the oppostion +3, free play.

Change these boundaries/constraints and change them often. Watch the players work hard to overcome, to learn what works for them. Watch as they create opportunities to win the practice.

It’s too quiet, turn up the noise and find the joy of true footballing expression amongst the chaos.