Improving the transfer of learning from training to match day through practice design

Transfer in sports training is a critical concept that examines the extent to which skills acquired in one context can be effectively applied to another. This process is vital in the world of sports, where athletes strive to enhance their capabilities and adapt their skills from training environments to actual competitive scenarios.

In football, the discussion on transfer is nuanced, involving near transfer and far transfer. Near transfer is when training tasks closely resemble the match, with the aim of ensuring a seamless transition of skills. Whereas far transfer involves tasks that deviate significantly from the competitive environment, requiring athletes to adapt their skills to unfamiliar and dynamic situations. We will explore these differences and how this knowledge can guide our practice design.

This learning of transfer extends beyond the physical actions, it also encompasses the cognitive and emotional aspects of the game. The way athletes process information, make decisions, and handle the emotional context of competition is crucial in determining the success of transfer from training. Additionally, understanding the key elements that influence practice design is essential for coaches striving to create effective training environments.

What is transfer?

the gain (or loss) in the capability to perform the criterion task as a result of practice in the transfer task

In other words, increasing (or decreasing) the capability to perform in a match/competition environment (criterion task) as a result of practice within a training/practice environment (transfer task).

Types of transfer in training

Near Transfer

training close to match day representation involves transfer and tasks that are similar (or often nearly identical) to competition

This usually occurs when the practice design in training is similar in representation to the game, making the learning process the most effective for performance. Already having knowledge of the skills in football makes learning a new skills easier. Coaches can aid this positive transfer by making sure the individual builds an understanding of the similarities between the two movement solutions (skills) and the environments they perform them in (training or match). An example of this is a football player using their knowledge of 1v1 skills against live opposition in practice and then transferring that understanding and movement solution (skill) on match day.

Far Transfer

training that is far away from match representation involves transfer and tasks that are dissimilar from competition

Far transfer is when the process of learning a skill does not expose the athlete to a variability of stimulus and, as a result, when they are in an unpredictable and dynamic environment (a match), the skill will require a different response (movement solution). For example, when a football player learns 1v1 skills against a mannequin and then tries to put that into a match situation where the defender will use a variety of strategies and force to destabilise and attack the player in possession. Has the player on the ball been given opportunity to learn to be able to adjust and adapt their skills to get success in training?

Highlighting affordances (opportunity for action) and questioning intention is key for players to develop their knowledge in the game along with dynamic and challenging ecological practice design.

Learning skills is a continuous process always in motion. The process of learning a new movement solution will be adapted from actions, experiences and ideas from the past, e.g. exploring a new passing skill will lean into information attained from their own experiences, what they have seen and what the task is. In addition to this, the development of the skills will also affect the solutions previously learned when used in the future.

Practices are not categorised into either near transfer or far transfer, all practice designs will be somewhere on the spectrum above. We can understand that where our practice design might be is based on how many of the key elements are present within our practice design. It is unrealistic that all of the elements of a match will be represented as it is very hard to replicate a game environment due to the many variables. These include the crowd or parent pressures that the players will face, as well as the unpredictability of the opposition to name just two. However, there are factors that we can control, and, as coaches, it is our duty to be aware of this.

What is everyone else saying?

Common elements theory (Thorndike, 1931)

The determinant of transfer was the extent to which two tasks contain identical elements: the more shared elements, the more similar the two tasks, and the more transfer there would be.

Thorndike, E.L. (1931) The fundamentals of learning. American Journal of Psychology

Instance theory (Logan, 2002)

Skills are highly specific to the events experienced during training. That is, unless an event has been experienced during training, a response to this event will not be skilled.

Logan, G.D. (2002) Automaticity and Reading: Perspectives from the Instance Theory of Automatization.

Appreciating the research and work done over the years will guide and help our understanding of transfer from practice to competition. Leading professors play key roles in how our organisations shape the coaching methodologies at the elite level in both performance and development sectors of football. Therefore acknowledging the importance of the work Logan and Thorndike have done is impossible to ignore.

Where do these sit?

Below are some session plans, figure out where you would put them on our ‘Far and near transfer spectrum’ shown below.

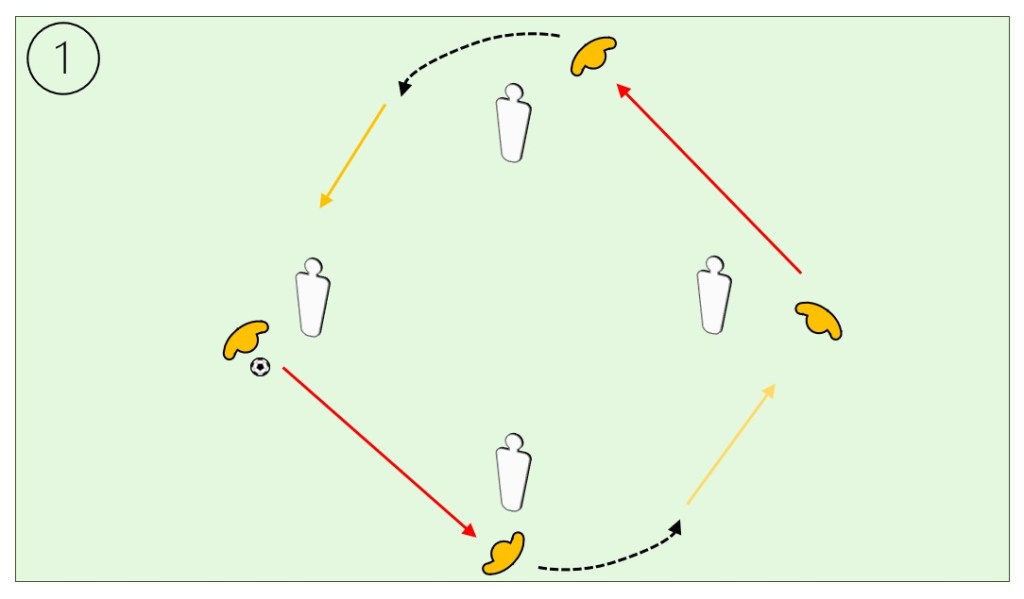

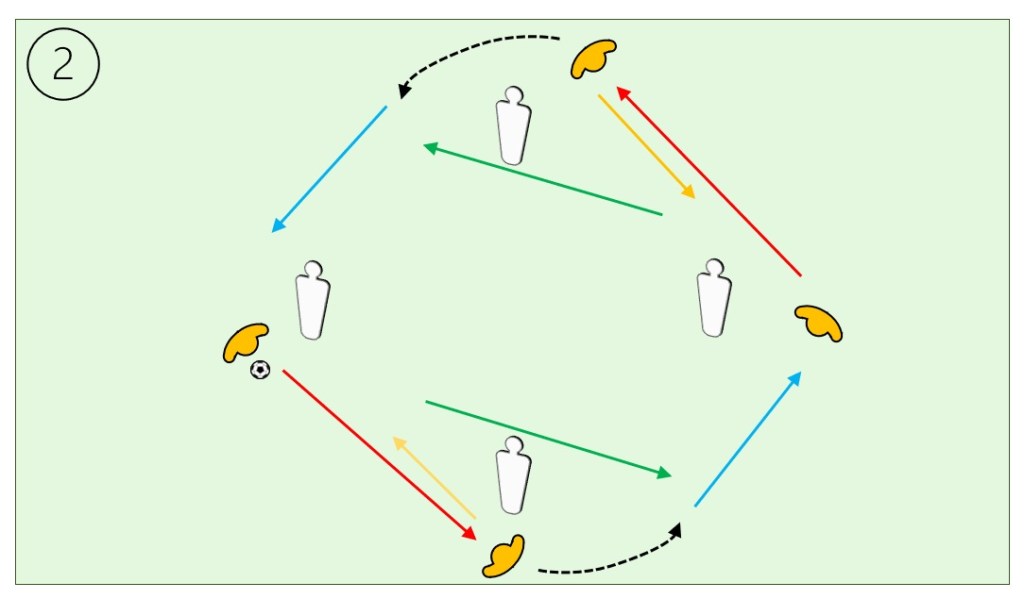

Practice 1 with progression – Passing Pattern

- Red line is the first pass / Yellow is the second / Green is the third / Blue is the fourth

- Players follow onto next mannequin

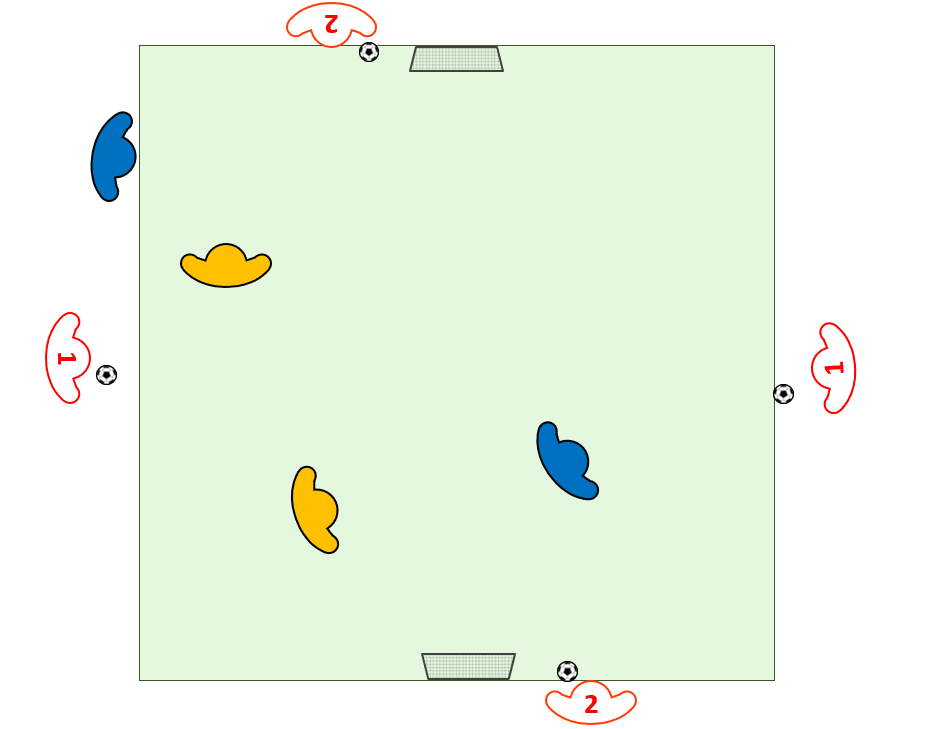

Practice 2- 1v1 to evade, entice or eliminate pressure

- White stays on outside / Blue vs Yellow in middle area

- Blue attack first and should try to receive from White

- If receive from White 1 they can score in either goal / If receive from White 2 they should score in opposite goal

- Blue stays attacking and Yellow stays defending / First to 5 goals for either defender or attacker then swap with pair from outside / Attacker should always receive the ball / Attacker should reset the 1v1 by exiting out the area each time

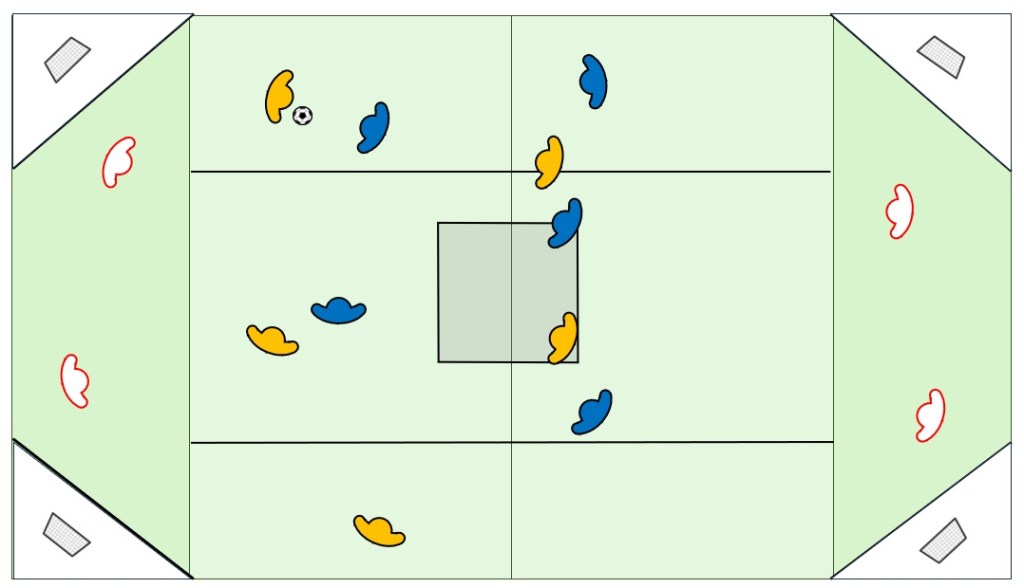

Practice 3- 5 v 5 + 4

- Blue vs Yellow in middle area with end zones

- Blue team defends end zone behind them and attacks into end zone in front (same for Yellows)

- Red players to act as end zone players either strikers or centre backs depending on which team is in possession and the direction they are attacking

- To score the team in possession must play into end zone players to unlock the mini goals in their attacking end zone

- Progression

- Use of marked out thirds and/or middle square to guide attention for playing into different areas

- Red players must assist 1st time or they play out for the opposition

Using our knowledge of the elements and principles for practice design to give the players near or far transfer, where would you put the practices above? Where would you put some of your own practices?

The players need to be a part of sessions that require adaptability and this can only happen within an unpredictable and dynamic practice that is near to competition. Players should not be given an answer so should be encouraged to explore and find their own solutions. Utilising trial and error, guided discovery and opportunity to reflect coaching strategies are key for players to build their knowledge in the game. There is not just one way to find success in a football match and no situation is ever the same. With this in mind it can help guide our practice design and the affordances our players will interact with by doing our best to try and replicate match day as much as we can.

Good decision-making in football relies on strong cognitive functions, particularly executive functions like response inhibition, cognitive flexibility, working memory, and attentional control. For instance, when a footballer intends to shoot at goal during a scoring opportunity but faces an unexpected change in the environment (a defender blocking or the goalkeeper moving), their ability when starting the action of the initial shot and adapting to the situation is crucial. Recognising the importance of these cognitive skills, sports organizations globally are heavily investing in cognitive testing and development as a key aspect of talent identification and development in football.

The premise is that footballers who are adaptive tend to excel on the field, and this can be developed over time. We are trying to design practices that offer the players opportunity to improve their cognitive performance but this can only be achieved through near transfer practice. Our role as the coach is to empower and highlight the athlete’s attention and intention so they can self-organise and try again.

Part 2: Straight from the training ground

What needs to be in practice design for transfer of learning

In the second part of ‘Straight from the training ground’ we will explore what is needed in practice design for near transfer to occur and how we can ensure our training has all the key elements of competition. We will also go in-depth around the 4 components for transferrable practices as well as a list of questions to ask yourself about your own practice to reflect and help guide your coaching on the grass.

Click here for Part 2: Straight from the training ground

Conclusion

Transfer in sports training is the ability to apply skills learned in one context to another, crucial in sports where athletes aim to adapt training skills to competitive scenarios. In football, near transfer involves closely resembling match conditions, while far transfer requires adapting skills to unfamiliar situations. Transfer extends to cognitive and emotional aspects of the game and this should influence practice design.

Near transfer, close to match representation, involves similar training to the game, enhancing effective skill transfer and cognitive development. Far transfer, distant from match representation, lacks variability, asking athletes to adapt skills in predictable situations. Practices fall on a spectrum between near and far transfer, influenced by key elements. Coaches should aim for adaptability in sessions, utilising trial and error, guided discovery, and reflection for players to develop game knowledge. Football decision-making relies on cognitive functions and near transfer practice design is imperative to improve a player’s performance. Ensuring our practices have as many of the key elements represented as possible.

The goal is to design practices for near transfer, empowering players to improve cognitive performance through self-organisation. Coaches play a vital role in guiding attention and intention for the player and giving time for the athlete to calibrate and adapt these, replicating match conditions as closely as possible to enhance player adaptability and success.

Bibliography

Logan, G.D. (2002) Automaticity and Reading: Perspectives from the Instance Theory of Automatization.

Thorndike, E.L. (1931) The fundamentals of learning. American Journal of Psychology

Fransen, J. (2022). There is no evidence for a far transfer of cognitive training to sport performance.