Knowledge of

Our team has a game this weekend. The players need to know how to press the opposition. We have three sessions to make sure they know how to press correctly. It’s easy right? There’s plenty of set pressing structures out there; Man City with their out of possession 4-4-2, Newcastle with their extremely high front line, Bielsa with his man to man press. But which one is right for us and our team? Maybe we’ll press with a front three, maybe a front two, maybe we’ll have one of our attackers sit on the opposition’s no.6.

Whichever one we choose, of course it’s for us to determine as the coach. And we’ll press in this structure no matter who we play against. ‘This is how I want my team to press…’ we’ll say. We win the ball back a record number of times. The stats back it up, we’re an out of possession genius! But what does this really mean? Does this demonstrate the player’s knowledge in the game or does this demonstrate our knowledge of the game?

What if by prescribing a specific pressing structure, even if seemingly successful, is actually restricting our player’s adaptability and their capability to see problems for themselves? Is this what we want to develop in our players? Do we treat them as robots, where we input the solution for them to execute? Are they the computers and we input the code? As youth developers, have we got the notion of out of possession development wrong?

What if no set pressing structure is the right answer? Would we not rather the players could dynamically organise, whilst in the game, to set traps and win the ball back for their team? Are we trying to give the players the necessary tools to succeed in top flight football, or are we simply showcasing what we know as coaches? Does this benefit us, or does this benefit them?

Success

In youth development this understanding of tactical solutions is great for us as coaches to have knowledge of. But we must be careful not to enforce this knowledge on the players as the right or only way to do something. There are infinite ways to defend and attack and our job is to make sure our players can recognise these in game situations and capitalise on them.

The pressure of parents, perhaps higher ups and peers in our coaching structure, all watching our team’s play on the weekend, is hard to ignore. We need them to know that we understand the game. We can’t have the players working through what they don’t yet understand. That would be too messy, and make us look like we don’t know what we’re doing!

We all want to feel valued and be looked at as successful. But what is success in youth development? I’m not sure it’s proving to everyone that we have knowledge of the game. And it’s certainly not players winning the ball back because the coach has told them where to stand and when to run.

Maybe real success is supporting the players in noticing how the opposition are trying to play and deceiving them to win back the ball. If we ask the right questions, and highlight the problems they don’t yet see, giving them space to come to a solution – this will not only make them more dynamic and adaptable, but will also develop their problem solving skills for years to come.

Right & Wrong

When developing young players, even as soon as u9s, there is pressure on the coaches to have their team look a certain way. We take control and tell them where to stand and what to do. We take the learning process away from them. So what’s the answer to this? Quite simply, we have to be strong enough to allow players the space to go through something we think is the wrong answer.

Confusion is actually a healthy part of learning. When a player is confused, this just means they are unsure of why a certain aspect of their game is failing. This is normal and often leads to motivation to highlight the problem and then to find an answer. If we give the players an answer first, they never feel this confusion, and therefore never find the motivation to learn.

So do we sit back and do nothing? No, but we have to be careful when supporting the players in the learning process. Highlighting problems to solve as opposed to solving the problem. Allow the players the space to fail, and then highlight what the problem was in the next individual or group conversation.

There is no rush in youth development. Allow them the chance to fix the problem themselves before we jump in and take the joy of learning away from them. They may even notice the problem and fix it through working together. They will then be more aware of this particular problem in the future. Maybe you’ll concede some goals, and maybe you’ll end up 6-0 down. That’s fine. We have to be comfortable being uncomfortable in the short term, for the players to flourish in the long term.

So with this new approach in mind, how can we support this long term development on the training pitch?

Knowledge in

How do we go about developing player’s knowledge in the game? How do we get them to a place where they can look at how an opposition team is playing, and decide where to set traps and win the ball back for potential goal scoring opportunities? How does this look on game day and how can we replicate this in training?

Firstly, we must step away from traditional instructional ‘there’s a right and wrong way to do it’ coaching approach. And move towards shared principles. Otherwise known as ‘shared affordances’. Maybe a shared affordance for the team is that we want to win the ball in front of the goal to set up goal scoring opportunities. Using this shared principle, there are now a myriad of ways to achieve this. And this will come down to how the opposition are set up, how they want to play and us noticing these problems in the game.

It’s important to figure out what you are trying to develop in your players. Ultimately, we are trying to improve their problem solving skills. We want to develop their ability to look at each unique situation and work together to find success. To do this, we must set them challenges and problems to overcome.

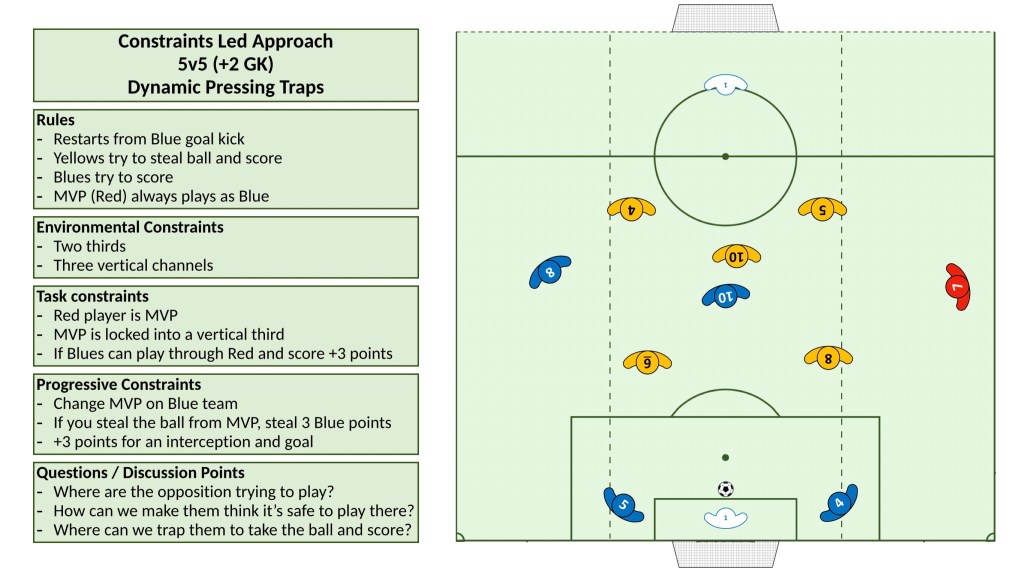

The above practice is aimed at doing just that. Blues are trying to play out from the goalkeeper with the aim to score. Red is not your usual magic player, they will only play for Blues. Blues choose a player to put on a red bib. The Red will play on Blue’s team, and if the Blues can play through the Red player and score, they will gain 3 points instead of 1. Red is your ‘MVP’.

What does this do for the out of possession team? Well, it gives them a problem to solve. The Blues are attempting to play through their MVP, however, can still choose not to use them if they deem them the wrong option. The set up is highlighting a potential game situation. The Yellows are now armed with the knowledge of where Blues would like to play, now it’s up to them to trap the Blue team, steal the ball and score.

It’s important to recognise, this practice is not designed to stop the opposition playing where they want, more to make them think they can play where they want and then have the ball stolen away from them in the process. The progressive task constraint of ‘+3 points for an interception and goal’ gives the players an extra challenge of intercepting the ball. Really making them think proactively about where the ball is likely to go.

Changing the MVP and the lane that they are locked into, brings a fresh yet familiar challenge. Allow the players discussion breaks, maybe disguised as half times. I like to do this when the score line is getting away from the team I’m working with, so they have a chance to re-diagnose the problem and overcome it together. This practice is not limited to outfielders, try making your goalkeeper MVP and see what the players come up with to trap them!

Lastly, if these challenges are being met, I would look to change some variables of the practice. The starting point: rather than a goal kick, starting with a pass back from midfield to a deeper player. Maybe from a throw. You can play with different versions of this to allow the same problem with a fresh outlook. Depending on numbers, playing with opposition formations will also bring a new challenge to the practice. Are they playing against a back four? A back two? A back 3? Changing the variables is something I would do when revisiting the session later in the week.

Inside or Outside?

Often a common coaching point discussed under the topic of pressing is, do you want your team to show the opposition inside or outside? My answer to this is, it depends on too many variables to have your team press in one specific way. I’ve heard too many times, that when it comes to coaching defending, it’s more ‘yes or no’ than attacking. I don’t agree with this statement.

There are infinite ways to defend specific situations and the context of each specific situation will demand using different tactics. This is why, if we want to develop the very best tactical minds in football, it’s important to set up a variety of problems for your players to solve. Every team you play against will play a different way and use different players more than others in build up.

Their individuals will also have different skill sets. What if one team has great 1v1 wide players and next team have a press resistant CDM. All of these variables will play a part in how your players approach the game. If you press one way, are you really helping your players assess the game? Are you helping them develop their knowledge in the game? Or are you showcasing your knowledge of the game?

Game day

When it comes to game day, the pressure on coaches from parents and peers is more immediate. There’s a lot of pressure on the players too. They are expected to show what they’ve learnt in training that week. But what happens if we’ve prescribed them a set pressing structure and the opposition have found a way to continually bypass it? The players feel like they’ve done something wrong, but they’ve followed what we’ve asked of them to the letter!

It doesn’t look good for us either, the players on the pitch are, after all, a reflection of us and the training they receive. It’s very easy to then slip into a more controlling mode, telling the players exactly what to do so they look good in the short term, in turn making us look like good coaches. This, in my opinion, is papering over the cracks. So how do we help the players on game day?

Firstly, let’s start with what a player led press looks like. Here’s some questions to help your players assess the problems on the pitch and support them in finding some solutions.

‘Where’s the danger?’

‘Where are they trying to play?’

‘Who are they trying to play through/into/onto?’

‘Where are their gaps and spaces? How do we close them?’

‘What’s worse for us right now, they play through the middle, around the side or over the top?’

Maybe you’ve noticed something about one of the opposition players, for example the CB having a skilful long range passing ability. Feel free to highlight this as a problem and ask the players to solve it. As they move to put pressure on the CB, they may leave a player behind them free, now highlight that to the players. ‘How do we stop the CB having time to play those long passes and protect the area behind our first line of pressure?’

Now what’s important to remember here is that there is not one answer to these problems. We have to work through it with the players. We are there, not to solve their problems for them, but to highlight problems and then have them work through them together, as a team. Imagine you took this approach in training and games for three months. Imagine all of the experience they would have, playing against different teams, with different variables in their playing out structures and all of the unique individuals they’d have to assess.

The plan is to get to a point where you have as little intervention as possible. The players will start asking the question, ‘where’s the danger?’ And they will begin to notice how opposition teams want to play. They’ll highlight the problems to their teammates and have experience of how to deal with a variety of build ups. You will have supported the development of their knowledge in the game.

Tactical

Here’s what Steve McClaren had to say after moving to FC Twente and speaking to young players from their academy in the Netherlands in 2012:

‘‘…They teach young players at eight or nine years old how to solve problems on the field for themselves.’’

“I remember one young lad I had who was a 21-year-old. We wanted to teach him a bit of tactics and a bit of formation work ahead of a game. He spent 20 minutes talking through what he would do against this team. It was in such an intelligent way and exactly what we’d been talking about.”

“I told him that his presentation was unbelievable and that no English player I know could’ve done that. I asked him where he’d picked that up from. He explained that he’d been doing this kind of tactical work and intelligence work since he was about 11 years old. That’s the difference between the two cultures.”

We still have an opportunity to lead the world in our approach to developing tactically advanced footballers, and players learning this side of the game will only help improve the overall level of the players we’re working with in the long run.

Are we so committed to a top down, linear approach to learning that we forget the real meaning behind what we do as youth developers? Are we there to give the players the answer, so they look good on a Sunday morning or are we there to give our players the ability to adapt to ever changing problems – with or without us on the sideline.

The next time you design a practice for your players, ask yourself the question – Is this showing my knowledge of the game or their knowledge in the game?